The nineteenth century was a period filled with steam engines, expanding railways, and great factories that changed the rhythm of daily life. It was also an age when countless individuals worked quietly in barns and sheds, sketching wild blueprints and shaping brass gadgets with their own hands, hoping to change the world in small and large ways.

These creators believed with unshaken confidence that every challenge of life could be answered with wheels, levers, and daring ideas. Some of the devices they built were far ahead of their era, while others were so peculiar that they feel like scenes from a dream when we look at their surviving patent pages and faded illustrations.

A Time of Restless Experimentation

In the 1800s the world felt wide with possibility, as if every discovery unlocked the door to ten more. Railways stretched like living veins across continents, steamships carried news and goods faster than ever, and telegraph lines stitched distant cities together in minutes, creating a sense that human ingenuity had no ceiling.

Amid this charged atmosphere, almost every town or village had at least one inventive soul bent over sketches for a machine that might save labor, transform travel, or simply amaze the neighbors. Many of these visions never left the workshop, yet their blueprints, prototypes, and hand drawn posters remain in archives and exhibitions, preserving the sparks of minds that refused to stand still.

The Walking Horse That Never Tired

One eccentric creation that captured public imagination was the mechanical walking horse. It was built with carefully carved wooden legs that moved like those of a marionette, each joint linked to a maze of cranks and gears tucked inside a hollow frame, and when set in motion the entire structure gave the eerie impression of a creature brought to life by machinery.

The inventor claimed with great pride that this marvel could travel across rough fields without ever growing weary and could carry soldiers through places where living horses would falter, and newspapers soon described lively demonstrations in town squares where curious crowds gathered, some laughing at the awkward stride while others whispered that they might be witnessing the future of transportation itself.

Though no army ever adopted the design, the sight of that wooden beast lumbering forward became a symbol of human persistence. It showed that people were willing to rebuild nature itself if that could solve a problem. The strange device faded away yet its drawings remain as proof that even failure can carry charm.

The Automatic Hat Tipper

Victorian society cared deeply about manners. One unknown genius tried to make politeness mechanical with the automatic hat tipper. A small lever attached to the brim was connected through a spring to a motion on the wearer’s coat. When the gentleman raised his arm, the spring lifted the hat with a flourish.

Ladies and children watching the demonstration were delighted, and the inventor proudly explained how this contraption would save effort while preserving dignity. It never became common, but in those years it was a sign that even the smallest gesture could be improved with clever engineering.

The Flying Machine that Hopped

Before airplanes ruled the sky, inventors tried to lift people with flapping wings and pedals. One creation from France combined a bicycle frame with long canvas wings. The pilot would pedal furiously, the wings would clap together like a giant bird, and the whole thing would bounce along a meadow without leaving the ground for more than a few heartbeats.

Crowds cheered anyway, because the dream of human flight was irresistible. Even in failure there was beauty in those beating wings and spinning gears. The machine ended its days in a barn, its wood slowly fading, but the image survived in illustrated journals that praised bold attempts.

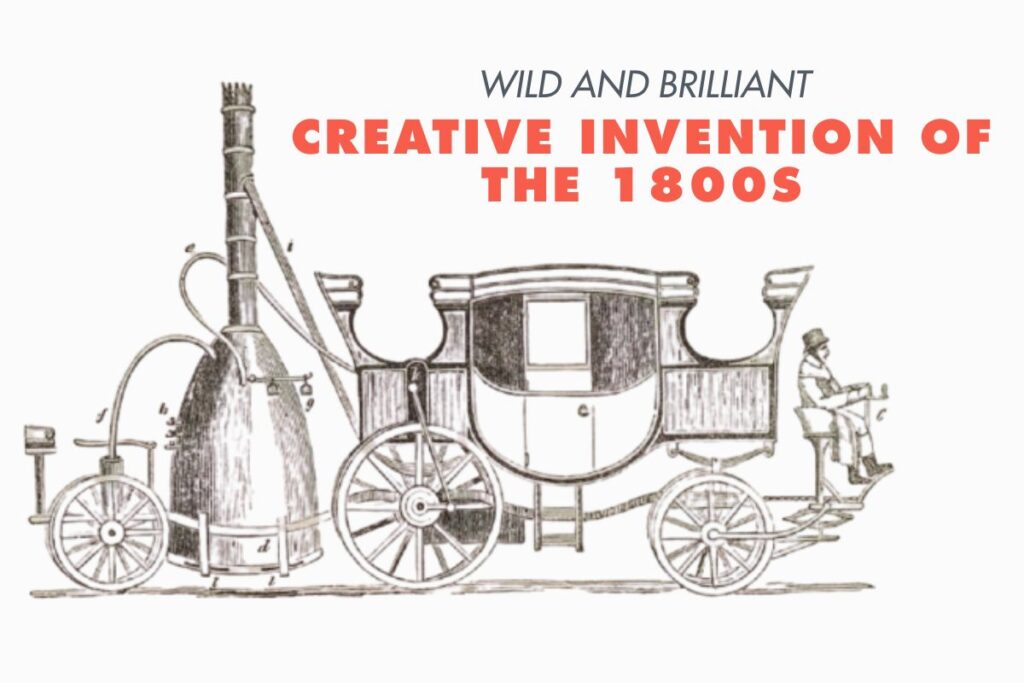

Rolling Wonders on Land

The 1800s also gave us experimental road vehicles that would look strange even in a fantasy novel. Steam carriages with tall chimneys rattled through town squares, alarming horses and thrilling children. Some had giant paddle wheels instead of normal wheels, meant to cross mud and sand with ease. Inventors held public races to prove their machines could outpace horses.

These carriages were loud and heavy, leaving clouds of smoke behind them. They often broke down on rough roads, yet they sparked imaginations. Each new model carried the promise that ordinary people would one day travel swiftly without needing an animal at all.

A Kitchen Full of Curiosity

Not every invention roared with engines. Some were small wonders meant for the home. The self turning roasting spit used a clockwork mechanism that kept meat slowly spinning over a fire, saving the cook hours of labor. The expanding toast rack folded flat after use, charming buyers who valued tidy shelves.

Everyday meals became a stage for clever design. Even humble egg beaters received winding handles and polished brass fittings, turning breakfast into a small performance. Looking at these tools today feels like meeting the ancestors of modern gadgets.

Curiosity in the Streets

Street life in the nineteenth century was filled with small inventions. Folding umbrellas with complex ribs appeared in markets, portable writing desks with hidden drawers delighted traveling salesmen, and mechanical fans offered a breeze in crowded halls. Each object carried a spark of ambition, a belief that life could always be made easier or more refined.

Some of these devices failed to catch on because they were costly or delicate, yet the very act of inventing filled the age with excitement. People did not see limits, only opportunities to try again.

The Legacy of Unusual Genius

Looking back at these eccentric inventions is like opening a cabinet of curiosities. Each design tells us about the way people once thought and hoped. Even the strangest machines reveal a serious desire to shape the future with imagination and tools. There is a tenderness in seeing how much care they poured into their work, knowing that the world might never fully embrace it.

These creations, saved in dusty archives and old journals, remind us that progress is built on countless dreams, some triumphant and others quietly forgotten. When we see them now, we do not only see failure or success. We see the spark that drives humans to keep building, keep improving, and keep dreaming, no matter how unusual the path may be.