Some were gentle giants, some were flightless birds that waddled straight toward their predators, and others were fierce and rare, having survived for millions of years before a rifle or a rat brought their story to an end. We didn’t lose them to time or nature; we ended them ourselves.

You might have seen some of them in museums, standing behind glass as taxidermy or wired together as skeletons. They were real animals with habits, homes, and histories, and it was us, the humans, who brought their stories to an end.

The bird that forgot to be afraid

The dodo lived on the island of Mauritius, with wings that no longer worked and a beak that curved like a question mark. When the first sailors arrived, the dodo walked up to them, having never known a predator before.

By the late 1600s, the dodo was gone, hunted for food, its eggs destroyed by rats and pigs, and the last one passed away without anyone bothering to record it.

A whole sky once moved with wings

There were once so many passenger pigeons in North America that people said their flocks could block out the sun, flying in ribbons across the sky that twisted and roared like smoke. At their peak, their numbers reached into the billions.

We targeted them anyway and finished them in wagonloads, selling their bodies packed tightly in barrels. The last one, named Martha, died in a zoo in 1914, and the sky has felt emptier ever since.

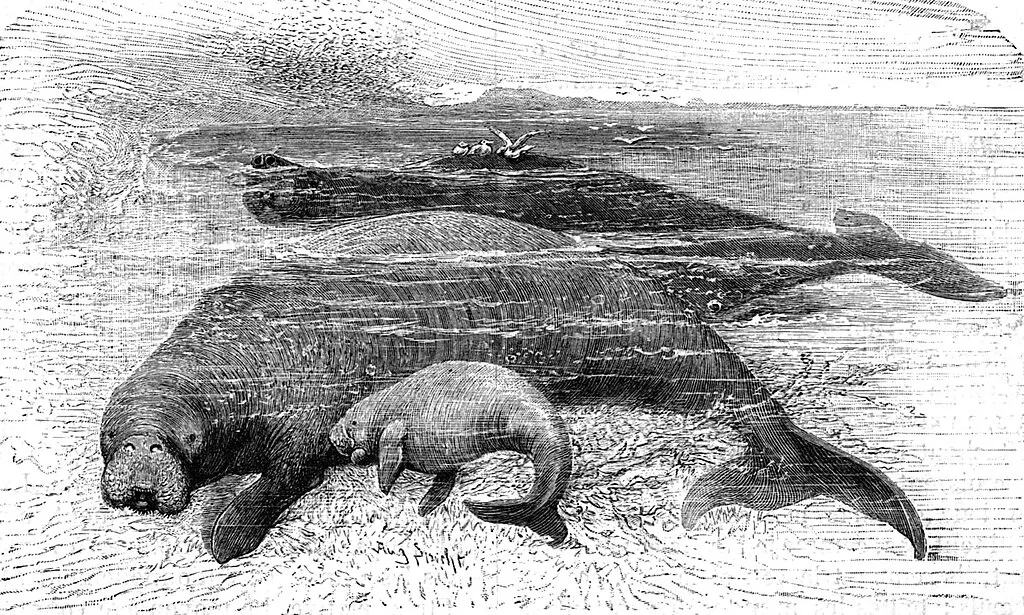

The sea cow we discovered and ate in one generation

When German explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller saw the Steller’s sea cow in 1741, he wrote about its immense size and gentle nature as it floated in the icy Bering Sea, munching on kelp and barely moving. He described them as peaceful as cows and slow enough to touch.

Twenty-seven years later, they were all gone. Hunters had eaten every last one, and that was the full extent of the species’ time with us.

The zebra that faded like a memory

The quagga looked like a zebra drawn by a forgetful artist, with stripes in the front and a plain brown back. It lived in the grassy plains of South Africa and was already rare by the time scientists began to take interest.

It was hunted for meat and hides until the last one passed away in a Dutch zoo in 1883, without anyone ever having studied it closely while it was alive.

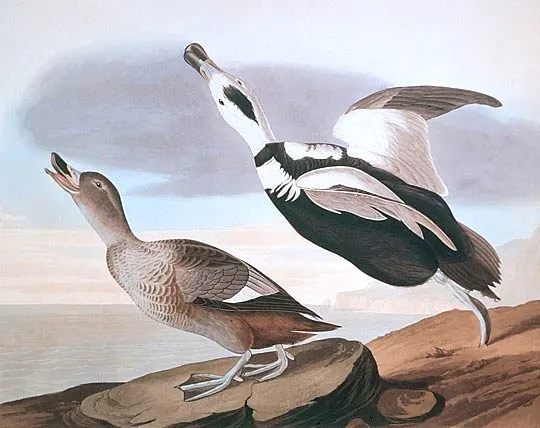

A bird that could not fly and could not run

The great auk stood upright like a penguin, with a beak that curved like a blade, and it lived on the rocky islands of the North Atlantic. It waddled on land, swam like a bullet through water, and trusted too easily.

People came for its down and its meat. In 1844, the final pair were crushed to death while guarding their egg, which was smashed during the struggle.

The dolphin who once ruled a river

The baiji, or Yangtze river dolphin, swam through Chinese waters for 20 million years, pale blue and nearly blind, gliding gracefully through the muddy river it called home. It communicated in soft clicks, navigating a world that had changed faster than it could adapt.

Then came boats, factories, and nets, and the river grew loud and fast, so by the time we looked for the baiji in 2006, it was already gone.

The tiger erased from maps

The Caspian tiger once roamed the plains and forests of Turkey, Iran, and Kazakhstan, moving through mountains and marshes with power and stealth. By the 1930s, Soviet records showed entire military units sent to hunt them down.

By the 1970s, the Caspian tiger had vanished completely, yet people still search the old forests hoping to find one.

The tortoise that had a name

On Pinta Island in the Galápagos, a tortoise lived alone, known to scientists as Lonesome George, the last of his kind. He spent decades in a protected enclosure while people searched for a mate who never came.

When he passed away in 2012 an entire subspecies disappeared and all that remains is his body now preserved in a glass case in Ecuador.

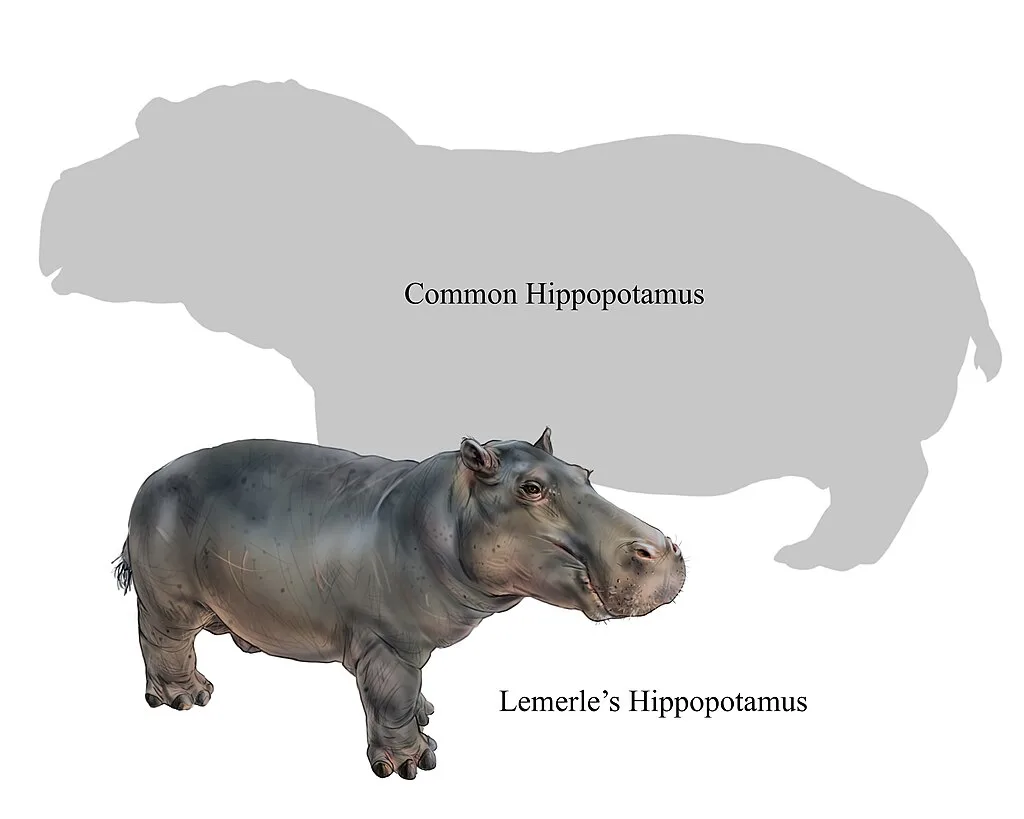

The hippo that walked through forests

In Madagascar, long after the dinosaurs, a dwarf hippopotamus lived, small and squat, moving through dense undergrowth far from rivers. Bones found in ancient human middens show that people hunted it with fire and stones.

Its existence survived in legends of animals that snorted through the night. But the hippo itself is gone.

The boa that lived beneath the ground

On Round Island near Mauritius, a species of boa buried itself in the soil to ambush prey, with pale scales and no venom, living a life unseen. When goats and rabbits brought by humans chewed away the underbrush, its world disappeared.

The Round Island burrowing boa was last seen in 1975, and while the soil remains, the snake is gone.

The duck that slipped away quietly

The Labrador duck may have always been rare, nesting along the cold coasts of Canada and spending winters on the American Atlantic. People believed its meat tasted fishy and found it difficult to hunt, so it was mostly ignored.

It disappeared anyway, with the last one seen in the 1870s, and no one truly knows why.

The volcano bird that baked its eggs

In Fiji there lived a bird that buried its eggs in warm volcanic soil, using the heat of the earth instead of sitting on them. When the eggs hatched, the chicks dug their way out and walked straight into the forest on their own.

Humans ate the eggs and burned the forests, and after that the eggs never hatched again.

The elephant with straight tusks

In the warm forests of Ice Age Europe there lived an elephant larger than any alive today. It had massive straight tusks and a domed skull that humans once painted on cave walls.

Eventually they hunted it, and its bones are scattered across Europe as reminders of what once lived there.

The ibex we cloned for one brief moment

The Pyrenean ibex lived in the mountains between France and Spain, climbing cliffs with ease and carrying horns that curled like sabers. It was declared extinct in 2000 when the last known one was killed by a falling tree.

In 2003, scientists cloned it from preserved tissue, and the baby ibex was born alive but died a few minutes later, becoming the first species to die twice.

We lose what we do not value in time

These animals were neither monsters nor mysteries, and they were neither mythical nor unknowable. They lived in forests, islands, and rivers until we arrived with ships and steel and fire, and whether they trusted us or hid from us, it did not matter.

They are gone now because fate never decided their end and because we ended them by failing to stop in time.