Bryan Charnley was a British painter who turned his illness into art. In the last months of his life he produced a series of self portraits that showed the effects of schizophrenia as it tightened its hold.

The first paintings still look close to realism, but with each new canvas the features shift, the expressions harden, and the face becomes harder to recognize.

He began the project in April 1991 after encouragement from Marjorie Wallace of the charity SANE. Alongside each painting he kept a short diary note, pairing his words with the images on canvas.

He also chose to stop taking his medication, believing it would allow him to capture the illness more directly. The decision made the portraits more intense, but it also weakened his health.

Charnley had lived with schizophrenia through most of his adult years. In Britain during the 1970s and 80s the illness carried heavy stigma, and treatment often meant long hospital stays.

He had trained seriously as a painter and hoped for a career, but his plans were repeatedly broken by admissions and relapses. He was never able to secure a stable place in the art world, though he kept returning to painting whenever he could.

By July 1991 he had finished what would be his final self portrait. Soon after, he ended his life.

The sequence he left behind has since been displayed at the Bethlem Museum of the Mind and preserved in the Wellcome Collection, where it is regarded as one of the clearest artistic records of schizophrenia.

Early Promise, Early Stumbles

Bryan Charnley was born in 1949 in postwar Britain. From a young age he showed interest in drawing and later chose to study art.

He trained first at High Wycombe College of Art and then at the Central School of Art and Design in London, where he hoped to build a career as a painter. His teachers encouraged him, and for a time he looked set to join the circle of young British artists emerging in the 1970s.

In 1971 he suffered his first breakdown. This was followed by long hospital stays and an eventual diagnosis of schizophrenia.

At the time the condition was poorly understood and often hidden from public view, and the treatments available brought difficult side effects. Charnley tried to continue painting whenever he was stable, but his studies and early career were repeatedly interrupted.

His biography and the record kept by the Bethlem Museum of the Mind show how these interruptions marked much of his adult life.

Still, he never abandoned painting. He produced portraits and still lifes in the periods between hospital admissions, though the breaks in his health meant he could not establish himself in the same way as his peers.

Later some writers described him as an example of outsider art, although his formal training made the label difficult to apply.

The Self Portrait Series

In April 1991 Bryan Charnley began what he called the Self Portrait Series. He set out to record schizophrenia in paint, and with each canvas he wrote a short diary entry to explain what he was experiencing. The project ran from 11 April to 19 July 1991, and the works are listed with notes on the official archive.

The paintings are oil on canvas, twenty inches square. At first the face is steady, then the features change as medication is reduced and symptoms rise. A later written account by James Charnley and Nick Bohannon confirms that Marjorie Wallace of SANE encouraged the diary that sits beside each work.

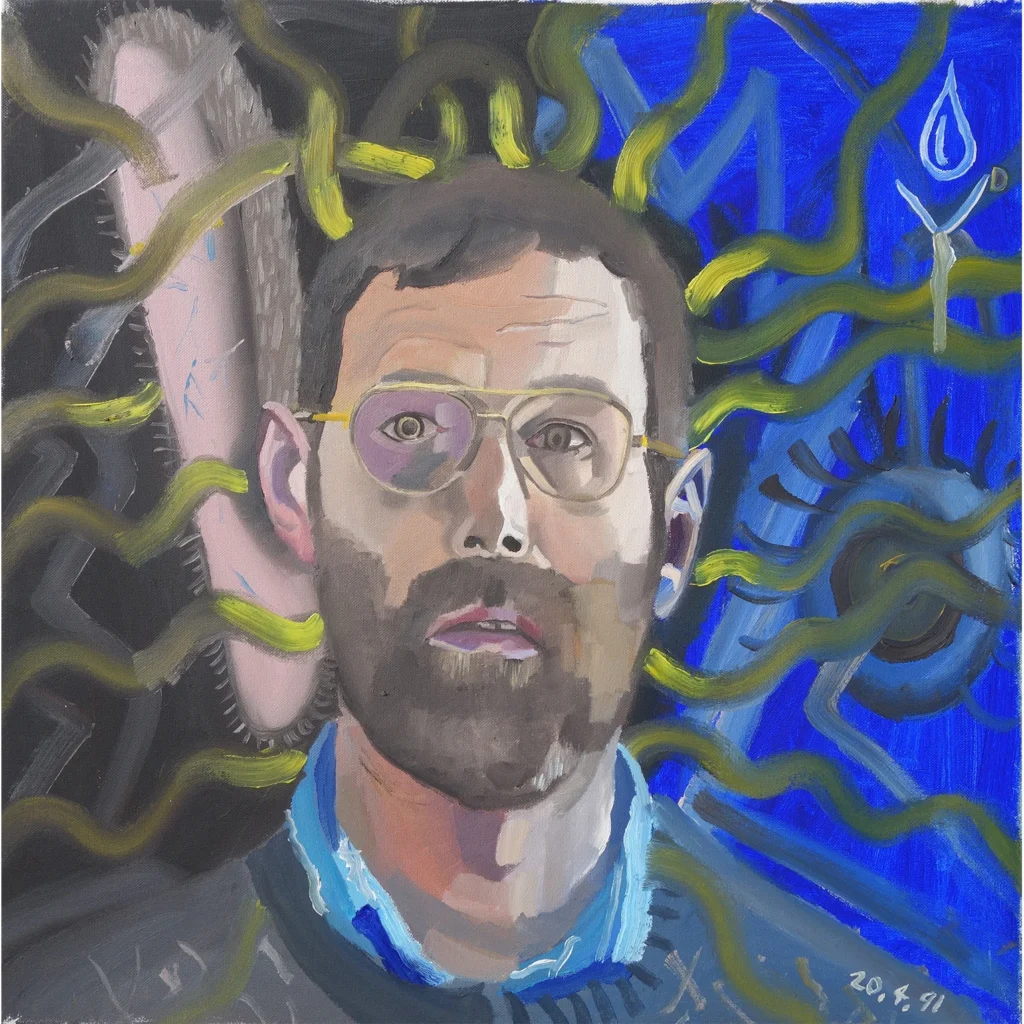

11-16 April, 1991

The first portrait is conventional and painted in two sittings while he was still on his full prescription. He notes that he slept a lot at this point. This sets the baseline for the series.

20 April, 1991

Bryan had cut back to one Depixol tablet and felt very paranoid. He believed his thoughts were being read back to him and painted a large rabbit ear to show how sensitive he felt to voices. The eyes look unsteady and the head already begins to distort.

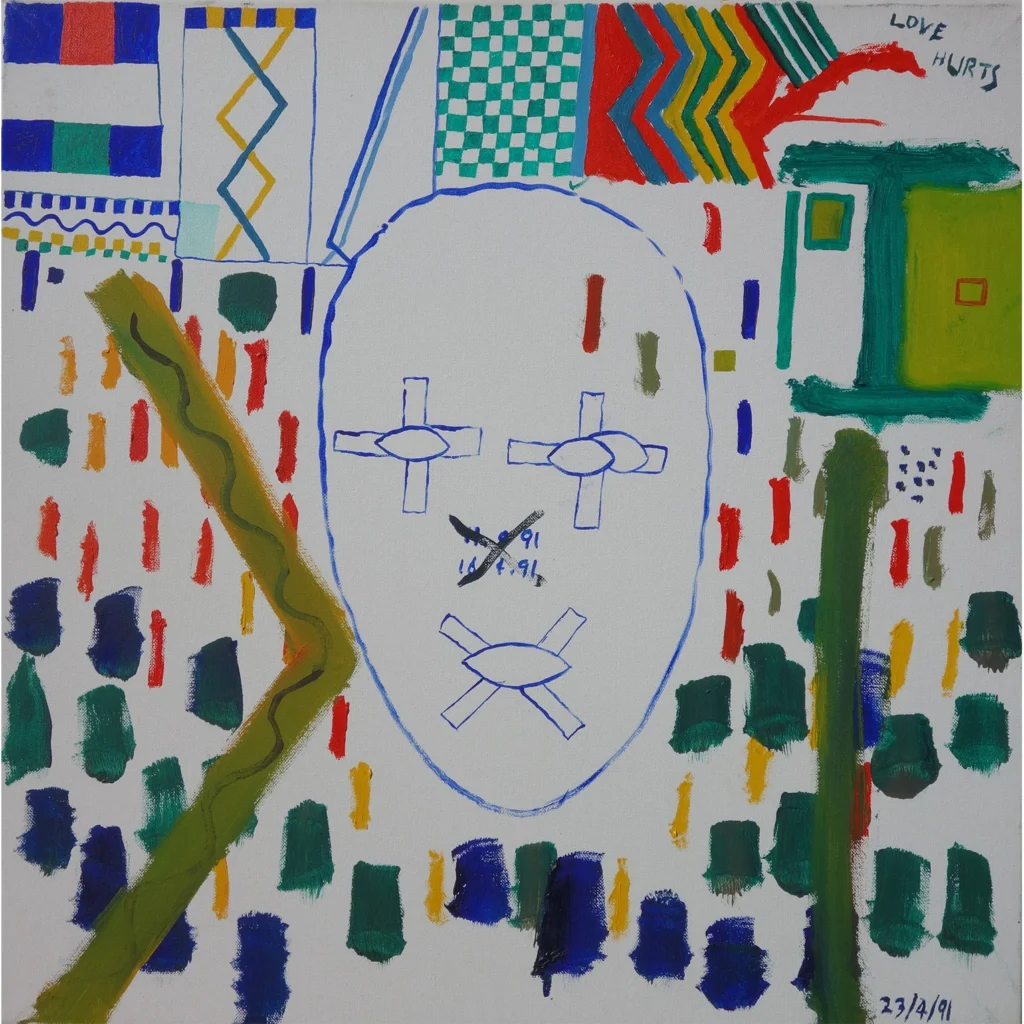

23 April, 1991

He wrote that his concentration was failing. He intended to show a disintegrating identity but found he could not hold form, so the face became a white mask with features partly removed. The diary frames it as a record of lost control rather than a planned design.

24 April, 1991

In his diary he wrote: “Why miss a golden opportunity to describe through paint total mental disintegration?” He cut his thumb and used his blood to make the red spots on the canvas, which he said reflected mental pain. The features are scattered and fading.

29 April, 1991

Charnley said things had got out of hand. He described a force telling him not to smoke and wrote that he swallowed fifteen Depixol tablets on the 24th to try to push back against pressure, which did not help. The portrait reads as agitated and restless.

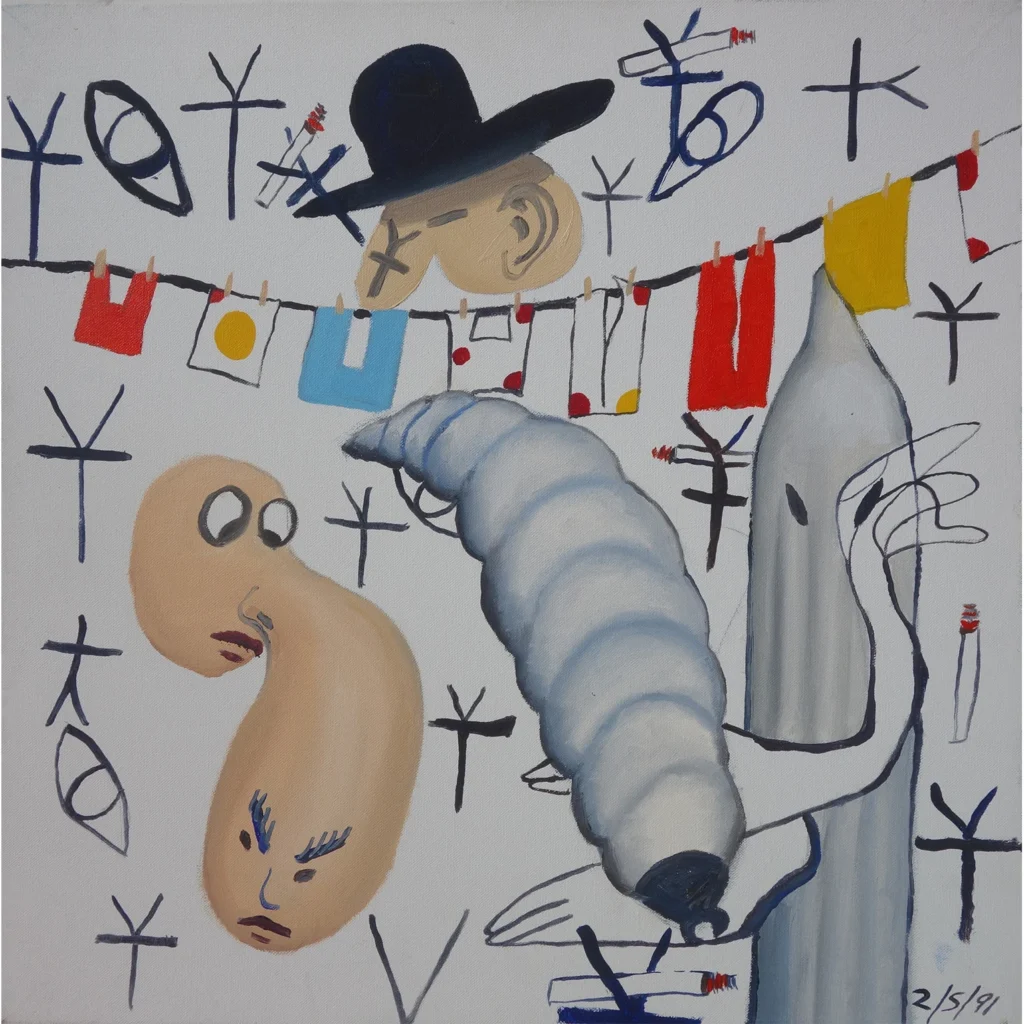

May 2, 1991

He wrote that the drugs’ chemistry had begun to take effect and he felt almost without energy, which he likened to a pupa state. He listed a set of symbols to explain his situation and conflict, and mentioned cutting back to 6 mg Depixol and 60 mg Tryptisol.

May 6, 1991

He said the nails in his eyes meant he could not see while others seemed to possess extra sensory perception. He added that he was on two Depixol tablets and two Tryptisol. The image follows his note, with lines crossing the face and vision blocked.

May 14, 1991

He described his ego as splitting like a cancer cell under attack and used a Roman soldier’s leg to express fear and humiliation. He connected this entry to the idea of crucifixion of the self. The text is explicit and the picture is harsh to match it.

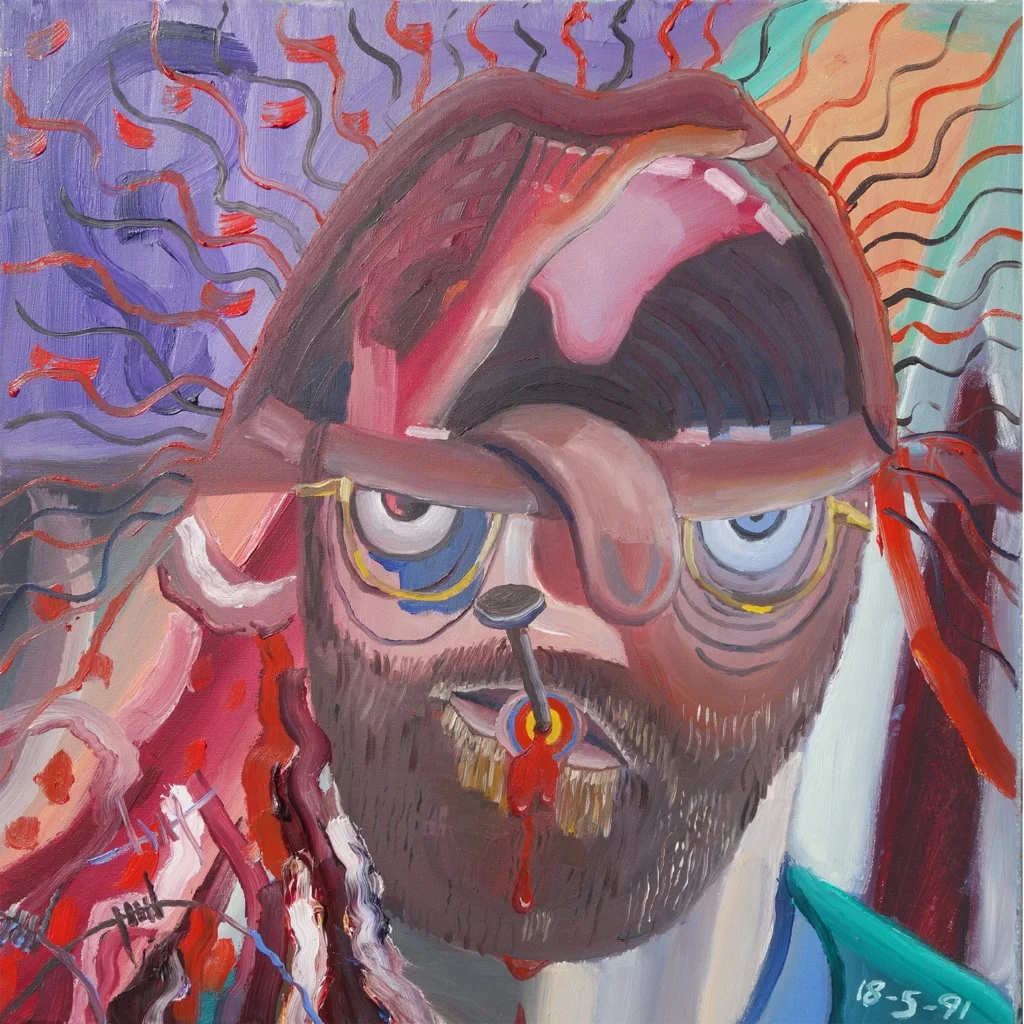

May 18, 1991

Charnley noted that he had cut back antidepressants and was no longer sleeping much. He believed his mind was broadcasting, so he painted the brain as a mouth to signify that. He also said his heart was broken, “gored,” and that this rupture pushed his thoughts outward. The portrait intensifies that rupture.

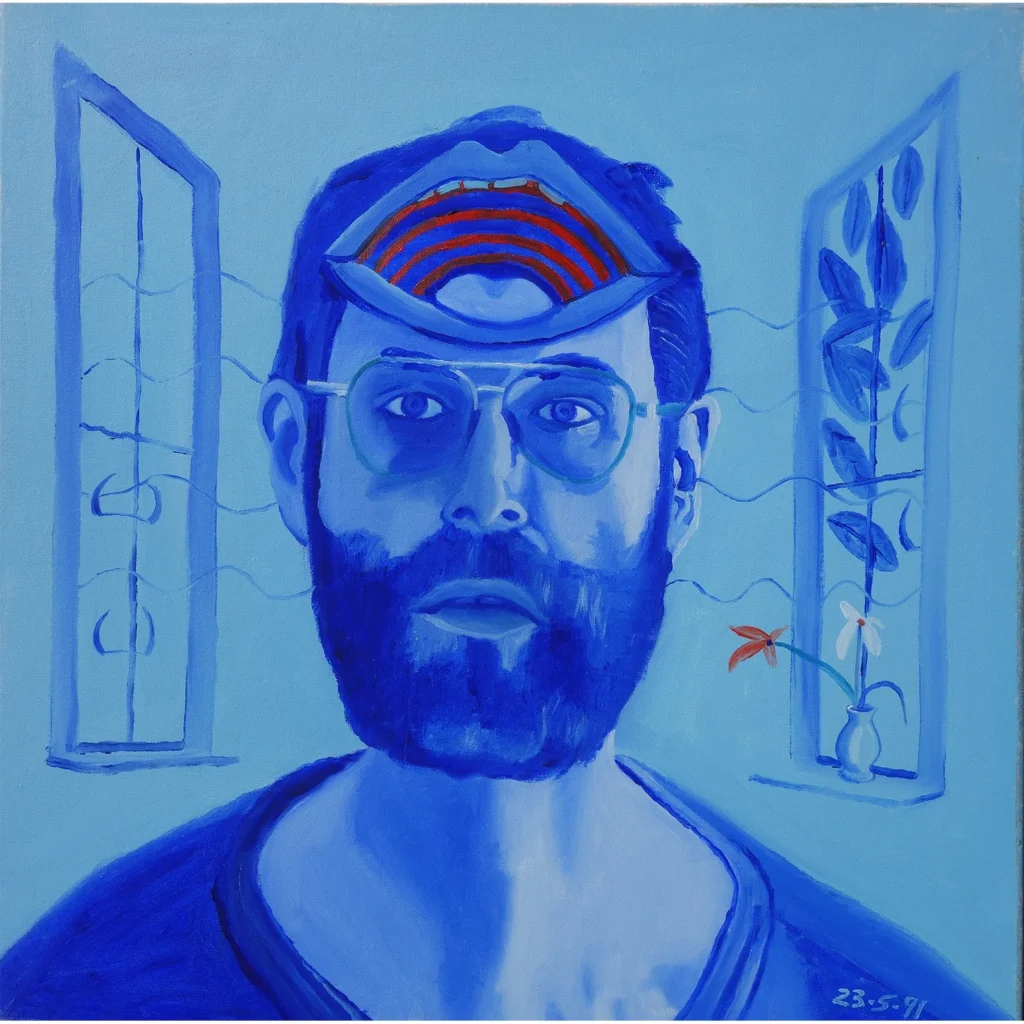

May 23, 1991

He said he was depressed after cutting back on antidepressants and painted the face blue. He wrote that voices from the street gutted him emotionally and that he tried to show thought broadcasting by turning the brain into a mouth for a second time.

May 24, 1991

In his notes he suggested “Perhaps a broken heart is the cause of it all.” He wrote that spiders’ legs represent his inhibitions, and that as his thoughts broadcast he felt ever closer to deeper symptoms. In the image the left side is wounded, the right side strung, the face rendered as a site of conflict.

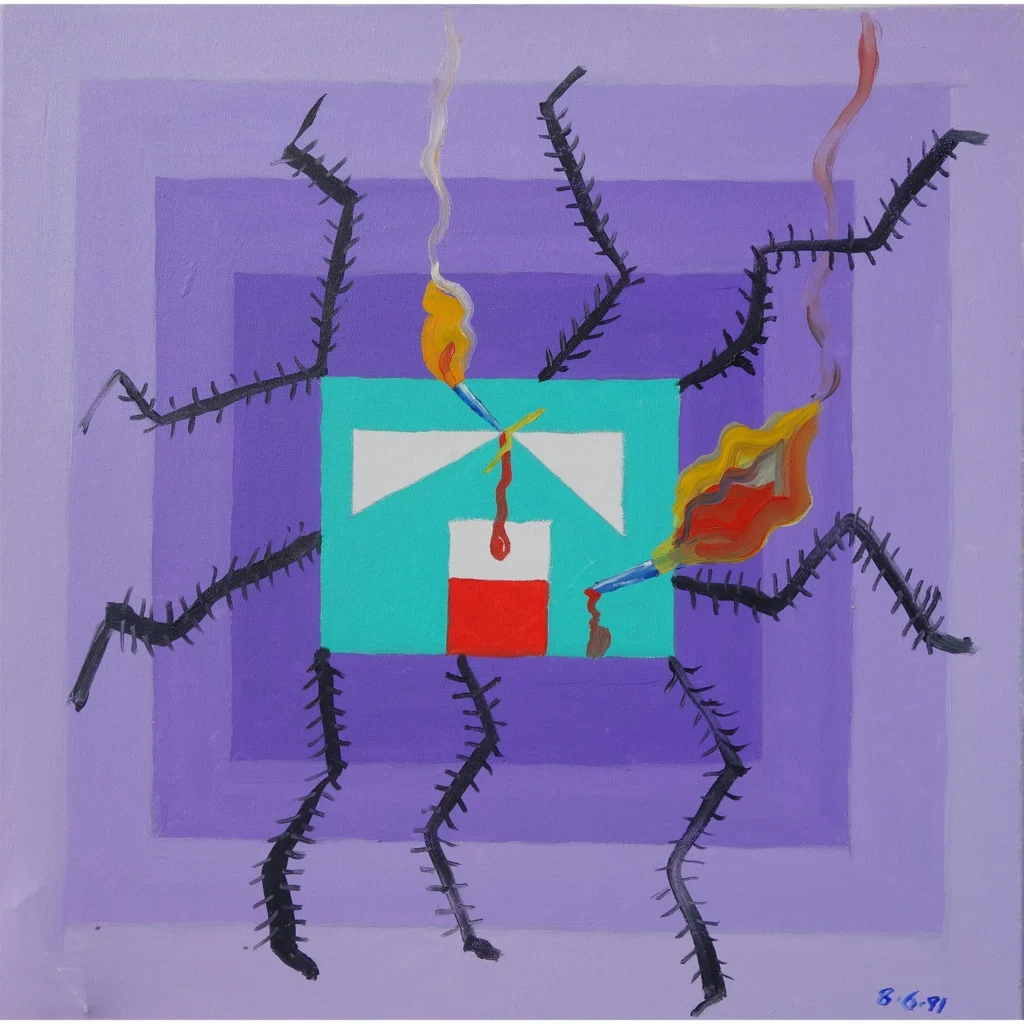

June 8, 1991

He mentions “spider’s legs” again, radiating outward and dissipating from his brain. He describes “flaming darts of ESP” piercing rational thoughts. The painting shows a weblike aura extending from the head, and the brain shifting in tension with white fields of thought.

June 13, 1991

He writes of emptiness, of heads stripped of secrets. He painted two eggs as empty vessels and crows like thoughts flying away. He says voices and gossip intensified his fears. The portrait is skeletal, voices in color, elements floating detached.

June 19, 1991

He asks whether others are intruding into his mental life, saying everyone has “a foot in the door.” He notes a silenced mouth, the tongue tied, as though he cannot reply. The image shows partial masking of lips, tension around ears.

June 27, 1991

He called this an extremely complicated picture and said he felt he was closing in on the essential image of schizophrenia. He wrote that he tried to be transparent, to exert control, and that his brain or ego was transfixed with nails. This is a turning point in the sequence.

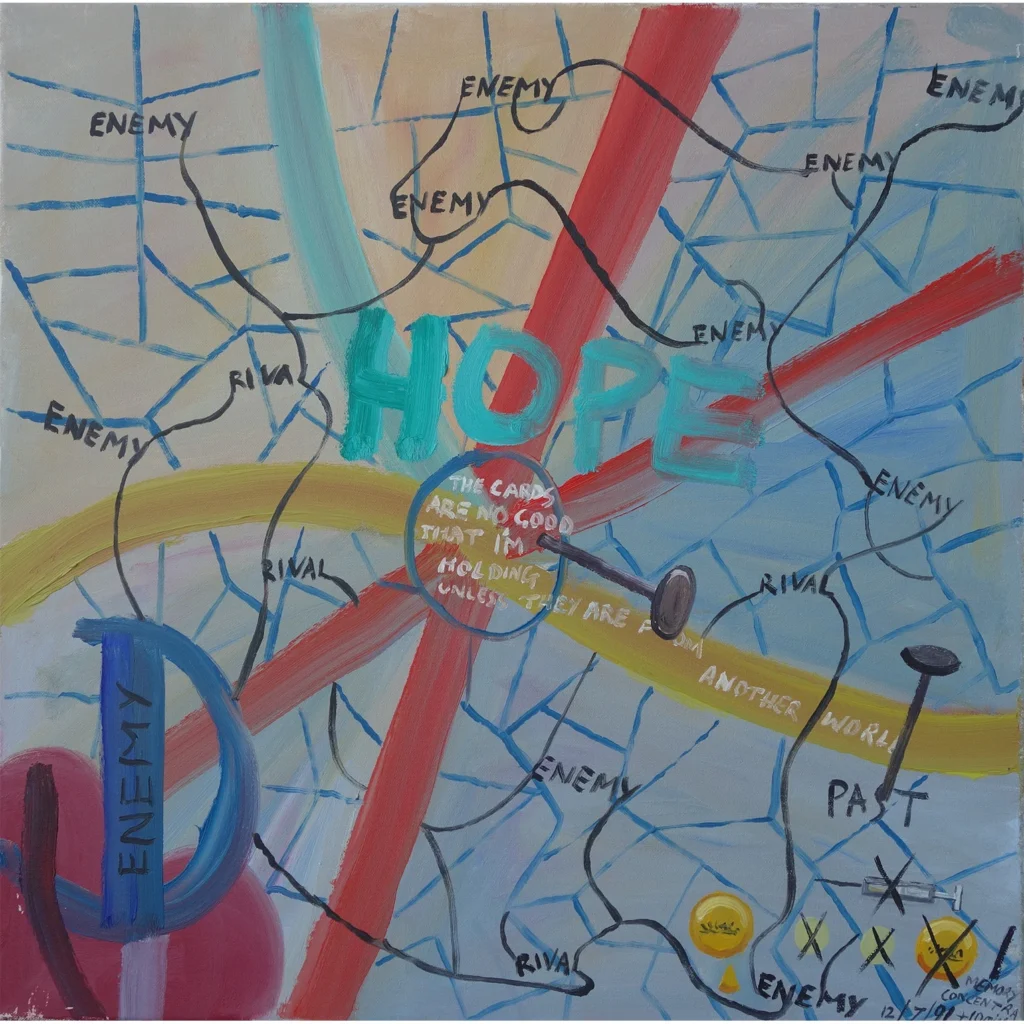

July 12, 1991

Charnley inscribed text on the canvas: “The cards are no good that I’m holding unless they are from another world.” He references Dylan’s lyrics. The words sit where the face would be and become the subject.

July 19, 1991

There is no diary note for the final portrait. The archive points out that red and yellow dominate here and elsewhere in the series when anguish is acute, and suggests looking back to 14 May and 12 July for the same colours. The face is almost gone.

After the Final Portrait

Bryan Charnley ended his life in July 1991 soon after the last self portrait. The sequence is unusual because each painting sits beside a daily note, so image and text can be read together.

Works from the series have been shown at the Bethlem Museum of the Mind and preserved in the Wellcome Collection. For readers who want to see the set with diary extracts, the official archive lists each portrait and date.

For broader context on artists and mental illness, see our piece on Louis Wain’s cats, where style changes track a long period of treatment and hospital life. For a plain guide to categories, see our explainer on outsider art and why training complicates the label in cases like Charnley’s. For background on care and stigma in Britain across the 1970s and 1980s, read our short history of mental health in late twentieth-century Britain.

This article stands as a hub. From here, readers can move to profiles that compare different paths under illness, including Richard Dadd and Yayoi Kusama, and a practical note on how to read diary-based art so symbols are taken from the artist’s own words rather than guessed at.

Thank you

I’m grateful that he had the courage and will to create this art and diary notes which can teach us some things about how the schizophrenic person suffers from the illness. I hope he is resting in a loving place with joy and without illness. I mean to say in happiness with God, and others may have their own views.

In Bryan Charnley’s Self Portrait series, he mentioned the effects of reducing his medication, specifically Depixol. I’m curious how this medication works in terms of managing symptoms of schizophrenia and what the common side effects are. Could anyone share insights or point me to information like that found here: https://pillintrip.com/medicine/depixol?

Great read and RIP Bryan 🙁