In 1991, two hikers on the Austrian-Italian border discovered a frozen body sticking out of the ice. He had been lifeless for over five thousand years. His skin held a surprise with dozens of tattoos made up of small dark lines and crosses etched into his joints and lower back. He came to be called Ötzi the Iceman.

The marks on Ötzi’s body were not ornamental. They were placed on points associated with joint pain. Researchers now think they may have served a therapeutic or ritual purpose, something closer to acupuncture than decoration. What matters more is that tattooing was already old in Ötzi’s time.

Humans have been marking their skin for thousands of years. Before needles were made of metal, they were carved from bone. Pigments came from soot or plants. Techniques varied, but the motivation often circled around identity. Who you were, where you came from, who claimed you, and who let you go were all marked on your skin.

In Japan, tattoos once marked criminal status before they turned into full-body illustrations. In the Philippines, they honored warriors. In parts of the Arctic, they passed from mother to daughter like heirlooms. For many, the skin became a record of duty, of loss, or of survival.

Ink as Protection, Ink as Punishment

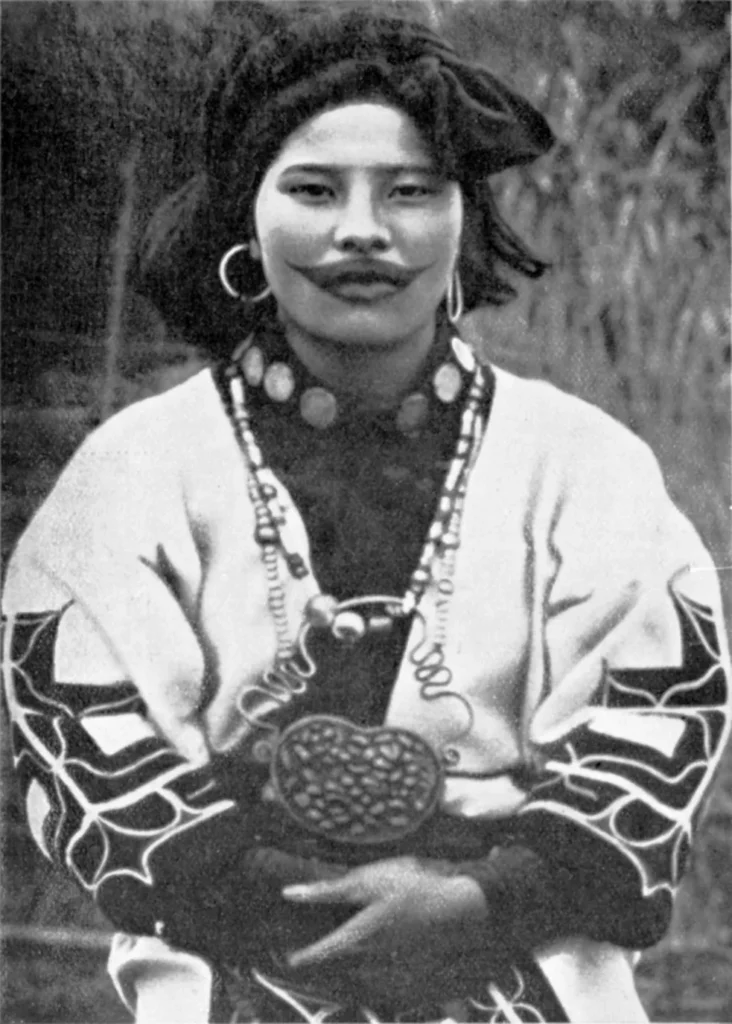

Among the Ainu women of northern Japan, tattoos followed a pattern. They began as small lines on the lips of young girls, growing more complex over the years. By the time a woman married, her mouth was surrounded by a dark, precise frame. The ink, applied through pain and patience, was believed to ward off evil spirits.

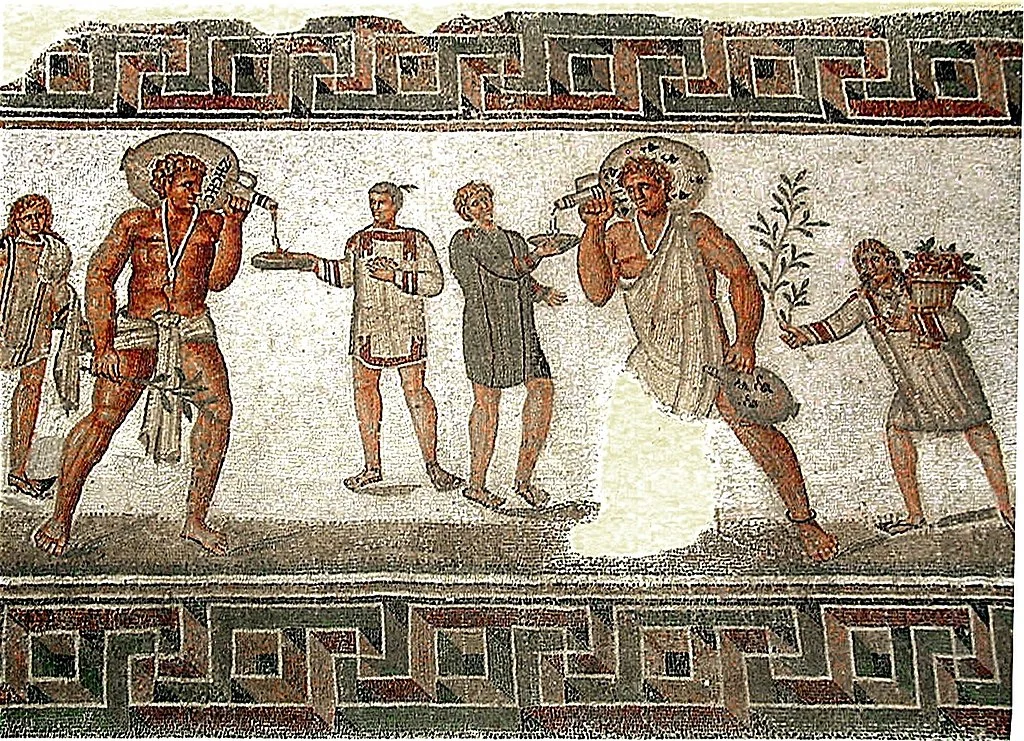

In contrast, tattoos were also used as tools of control. In ancient Rome, enslaved people were sometimes tattooed with the names of their owners. Some carried marks warning others not to trust them. The same practice appeared in early Chinese dynasties, where facial tattoos were used to punish crimes. In both cases, the marks served the state or the powerful.

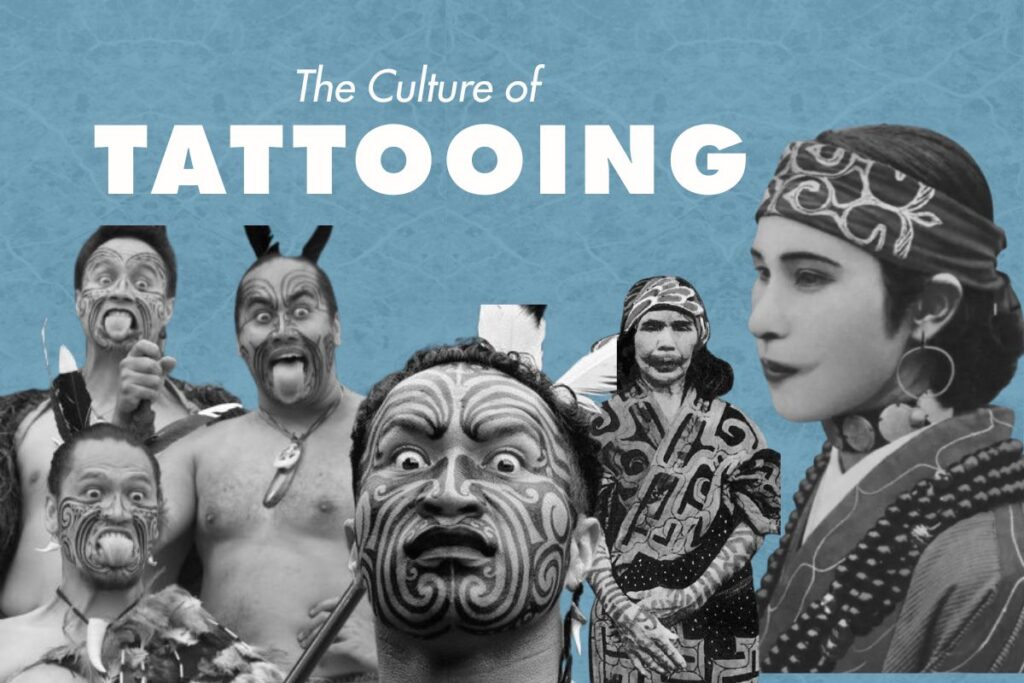

In Polynesia, the word tattoo comes from tatau, meaning to strike. The method involved tapping sharp tools into the skin using a rhythmic beat. The process took time, and sometimes brought infection or death. But those who survived wore their status in full view. Chiefs bore intricate designs across thighs and backs, each line loaded with genealogy and authority.

In 18th-century Samoa, tattoo artists called tufuga trained for years. When a young man received his pe’a, a dense tattoo covering the midsection and legs, he endured days of puncture work. The process required money, time, and the presence of witnesses, as tattoos functioned as social acts meant to be seen.

Skin Deep but Long Remembered

When Captain James Cook arrived in the South Pacific in the 1700s, his crew returned to Europe with something unexpected. Some of the sailors had received tattoos during their voyages. They became a novelty in Europe, where the practice had largely disappeared. For a time, tattooing became a sign of travel, of connection to something foreign and adventurous.

But the trend didn’t belong to Europe. On the African continent, skin marking took many forms. In Ethiopia and Sudan, Christian communities used forehead tattoos in the shape of crosses as both spiritual shields and social signals. In West Africa, scarification sometimes replaced tattooing, but the motivation remained similar. Marks carried the stories of kinship, bravery, and transition.

The Inuit of North America practiced facial tattooing among women for thousands of years. The lines and curves on cheeks and chins formed a grammar only locals could read. When missionaries arrived in the 19th century, the practice nearly vanished. But it never fully disappeared. In recent decades, descendants have revived the art, connecting memory to skin in deliberate ways.

In Thailand, sacred tattoos known as sak yant combine geometry and scripture. Traditionally applied by monks or spiritual practitioners, they are believed to protect the bearer from harm. These tattoos are still practiced today, often in temples, where the meaning comes not only from the ink but from the ritual that surrounds it.

The Body as a Map of Belonging

Tattoos once faded into the margins of global history. For much of the 20th century, they were associated with prisoners, sailors, and the working class. In parts of the Western world, they were seen as rebellion or deviance. But across most of human history, tattooing had little to do with defiance. It was more often about acceptance.

In Burma, older generations of Chin women still bear facial tattoos that once signaled tribal affiliation. In Cambodia, monks apply tattoos that mark commitment to spiritual life. In Iran, older Kurdish women recall palm tattoos that served as cosmetic adornment. The common thread is less about aesthetics and more about belonging.

In many Indigenous Australian groups, body marking functioned as part of initiation. In Papua New Guinea, tattoos often marked a woman’s first menstruation or a man’s first hunt. The marks told others where someone stood in the rhythm of life.

Even now, tattoos serve similar roles. Memorial tattoos commemorate those lost. Religious tattoos reaffirm belief. Family crests, flags, and even coordinates turn the body into a place of memory.

The tools have changed. Machines replaced hand-tapped sticks. Studios replaced ceremonial huts. But the impulse remains. People still return to the skin as a place to say who they are, who they were, and who they wish to remember.