The road north of Rockport runs flat and exposed, a long ribbon that can feel endless in the early hours, when the coastal wind is still cool and traffic is thin.

On the morning of July 9, 1973, a young man was found beside the northbound lane of Highway 35 near Rockport, Texas, dead after what authorities believed was a hit-and-run. He looked, by later descriptions, like someone who had not been shaving for long. He was tall and thin, dressed in light clothes for a Texas summer, including a straw hat and white Levi’s jeans, and he carried nothing that could easily settle the simplest question–Who was he?

For decades, the case sat in that unresolved space that haunts both families and investigators, the space where a person can be unmistakably real and still officially unnamed. The young man became a “John Doe” in posters and databases, a sketch and a list of measurements, a death ruled a homicide because the driver did not stop.

This week, Dallas police said that the teenager on the roadside had been identified at last. In a Jan. 2, 2026 statement posted on the department’s official blog, the Dallas Police Department said it had closed the decades-old missing-person case of Norman Prater, first reported missing in Dallas on Jan. 14, 1973, by connecting it to the unidentified hit-and-run victim found months later near Rockport in Aransas County.

The identification, police said, resolved two cases at once: the disappearance of a 16-year-old boy from Dallas and the long-running mystery of an unnamed teenager who died on a coastal highway.

The roadside death near Rockport that had no name

The details preserved in public-facing postings are stark and specific, the way official summaries often are when time has worn away the softer edges of a life. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children later described the unidentified victim as a young man in his mid-to-late teens, about 5-foot-10 and 145 pounds, found dead beside the road near Rockport on July 9, 1973. The organization’s poster listed a straw hat, a white shirt, white Levi’s brand jeans, a braided elastic belt with a gold buckle, and brown shoes.

What the same poster could not provide was the connective tissue: where he had been coming from, who last saw him alive, why he was on that stretch of road.

Dallas police, describing the same death in their Jan. 2, 2026 post, called it an “unrelated tragedy” at the time: an unidentified white male killed in a hit-and-run on Highway 35 in Rock Port, Texas, in Aransas County. They said local authorities and media outlets tried to identify him, but his name remained unknown.

The idea that the victim might have belonged to a missing-person case elsewhere, in a city hours away, is one of those connections that can feel obvious only after it is made. In 1973, counties and cities did not share information with the speed or ease now taken for granted. Even today, cold cases can persist for years because the clue that matters most lives in a separate file cabinet, a different agency, or a family album kept in a drawer.

ALSO READ: What happened to Sophia Koetsier, the Dutch medical student who vanished in Uganda

Norman Prater’s last confirmed sighting began at midnight in Dallas

In Dallas, Norman Lamar Prater was 16 years old when he vanished. The Charley Project, which compiles missing-person cases using public records and agency information, reported that Prater was last seen in Dallas on Jan. 14, 1973. Around midnight, the site said, he went to an all-night coffee shop where his mother worked and had a soft drink.

He did not arrive alone. According to the Charley Project, Prater was accompanied by two teenage boys with shoulder-length hair whom his mother did not recognize and an older Hispanic man she knew by sight. It is a small detail, almost cinematic in its specificity, and it has persisted because it is one of the last moments in which someone who loved him could describe him in real time–where he stood, who stood nearby, what he said next.

Prater told his mother he was going home and agreed to help her move the next day, the Charley Project reported. But he apparently never made it back. He was never heard from again.

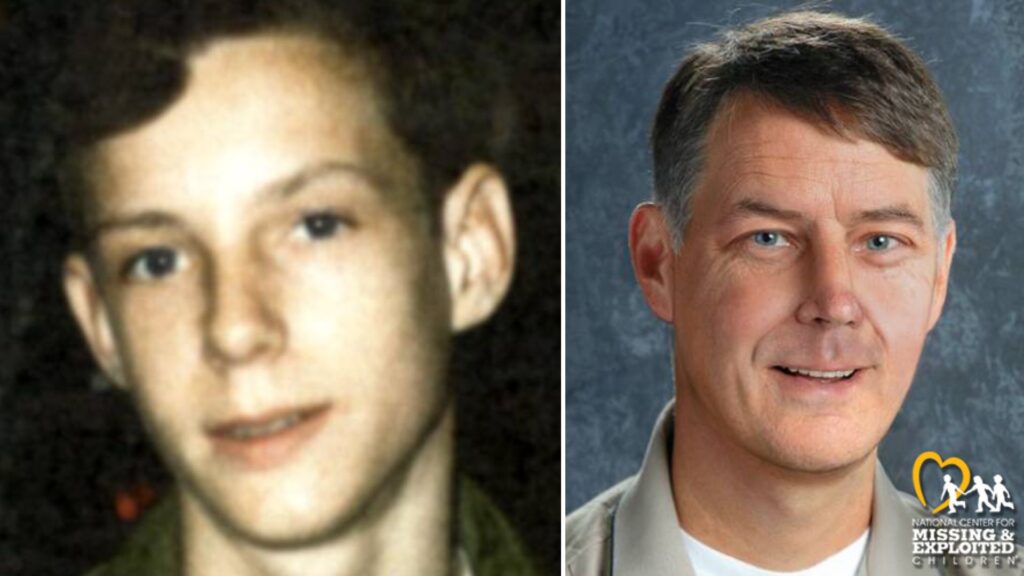

A missing-person poster published by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children captured the case in even plainer terms: Prater was last seen leaving his home on Jan. 14, 1973, and said he would be back shortly. He never returned, the poster said.

The Dallas Police Department’s blog post this week described the beginning of the case the way detectives would have written it into a file. On Jan. 14, 1973, the department said, Prater was reported missing by his family, and the investigation remained active but unresolved for decades.

Fifty-two years of posters, databases, and a life frozen in time

In many missing-person cases that last this long, the timeline stays short even as the years stretch out. A person is last seen and a report is filed. Then the case becomes a mixture of leads pursued and leads that never materialize, of records maintained and records lost, of family members aging while a teenager remains forever a teenager in the mind’s eye.

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children kept Prater’s case in its system with a Dallas Police Department contact number and its 24-hour call center tip line. The poster includes an age-progressed rendering, an attempt to imagine how a 16-year-old might look decades later, a kind of visual bridge thrown across time.

NamUs, the federal missing and unidentified persons system, also listed a case for Norman Lamar Prater as a missing person from Dallas with a last contact date of Jan. 14, 1973.

One consequence of that long span is that theories can accrete around a disappearance, especially one from the early 1970s in Texas, when fears about serial violence and runaway teens were part of the cultural landscape. The Charley Project noted that authorities looked into whether Prater could have been a victim of Dean Corll, the Houston-area serial killer known as the “Candy Man,” whose crimes against teenage boys and young men took place between 1970 and 1973.

ALSO READ: Mary Stewart Cerruti’s skeleton was found inside the walls of her Houston home

A detective’s second look, and the link between two 1973 files

Dallas police credited the breakthrough to Detective Ryan Dalby, who they said re-examined the Prater case and connected “key details” that suggested a link between the Dallas missing-person file and the Aransas County hit-and-run death. The department described the connection as a “compelling match” between the unidentified victim and Prater.

The statement does not publicly spell out what, exactly, made the match compelling. In cold cases, those details can range from physical descriptors to clothing, dental records, fingerprints, or family-provided information. What the department did say is that Dalby located Prater’s brother, Isaac Prater, and that contact allowed the detective to “conclusively confirm” the identity of the unknown individual as Norman Prater.

The human hinge of the case, as described by Dallas police, is that moment: a brother reached after a half-century, asked to revisit memories that may have been carried as grief and unanswered questions for most of his life. Dallas police said Isaac Prater now has answers about his brother’s disappearance.

In the department’s telling, the resolution is also a statement about institutional persistence. Dallas Police Chief Daniel Comeaux praised Dalby’s work and called it “a testament” to the department’s commitment “no matter how much time has passed.”

From Dallas to the Texas coast, the distance is still part of the story

The identification answers the most basic question–who the victim was–but it does not, at least in the public material released so far, explain how Prater got from Dallas to the coastal bend. The last confirmed sighting described by the Charley Project places him in Dallas around midnight on Jan. 14, 1973, at his mother’s workplace, saying he was heading home.

Dallas police did not say whether Prater left Dallas voluntarily, whether he traveled with anyone, or whether investigators were able to identify the people he was last seen with at the coffee shop. The department’s Jan. 2 post also does not describe any intermediate sightings or evidence that might map his movements over the next several months.

That gap matters because it shapes the kind of case this is. A missing-person report can cover a range of realities–running away, being coerced, being harmed soon after leaving home, being harmed later in an entirely different setting. A hit-and-run death months later suggests that Prater was alive for some period after his disappearance, but the public record available through these postings does not describe where he was living, who he was with, or what circumstances brought him onto Highway 35 near Rockport.

The same is true of the hit-and-run itself. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s poster says authorities believed the young man died from a hit-and-run vehicle collision and that the death was ruled a homicide, a classification that can reflect the driver’s failure to stop and render aid, among other factors. The Dallas Police Department’s statement described the incident as a hit-and-run but did not identify a driver or say whether any suspect was ever found.

If anything, the resolution underscores how a case can be both solved and unfinished at the same time. The name is settled, the missing-person file in Dallas is closed, and a once-unidentified victim is no longer anonymous. But the narrative arc between those bookends–Dallas in January, Rockport in July–remains thin in the publicly shared facts.

Anyone with information about the July 9, 1973 hit-and-run death near Rockport, Texas, can contact the Aransas County Sheriff’s Office at (361) 729-2222 or the Nueces County Medical Examiner’s Office at (361) 884-4994; tips can also be routed through NCMEC’s 24-hour call center at 1-800-843-5678, as listed on the public poster for the unidentified case.