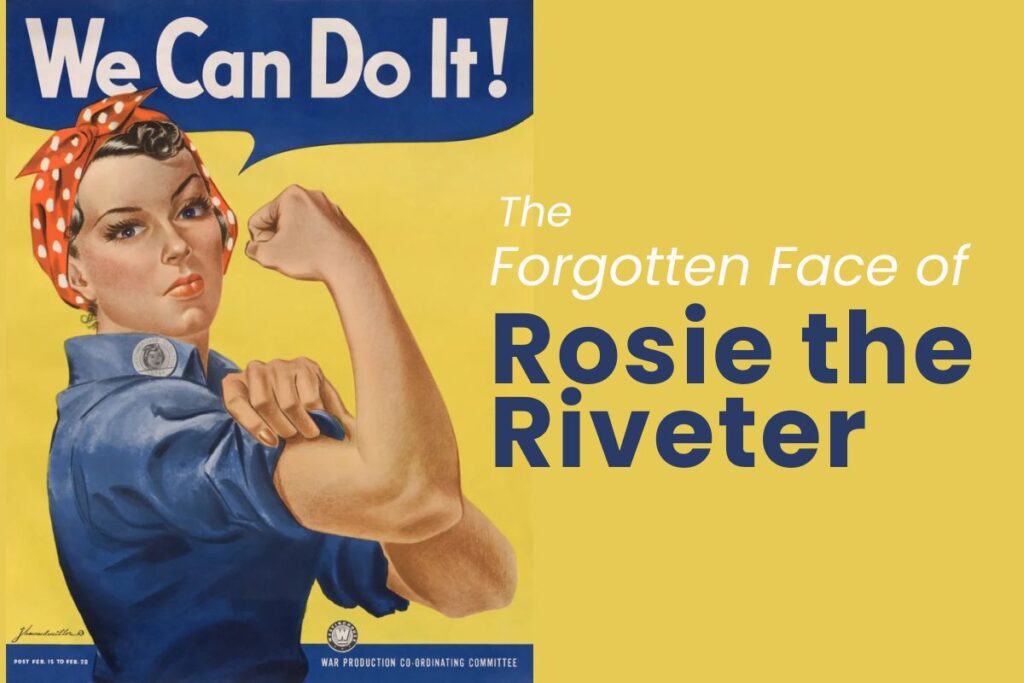

She wore a blue work shirt with rolled sleeves and a red polka-dot bandana that kept her hair back from her face. Her lips were painted, her gaze steady, and her right arm bent to show the curve of her bicep. In the corner of the poster, the words were printed in white over a navy speech bubble: We Can Do It!

The year was 1943. The poster was meant to boost morale among Westinghouse Electric employees, not the general public. It was displayed for just two weeks before being taken down and forgotten.

Decades later, it resurfaced and took on a second life. Feminist groups, labor organizers, and cultural critics turned it into a symbol of strength and resistance. The woman in the poster became known as Rosie the Riveter. But the face behind the image remained unnamed, or worse, misidentified.

The Woman in the Photograph

In 1942, a photographer from the Acme news agency arrived at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California. He had been assigned to capture images of women who had stepped into jobs that were once reserved for men. One of those women was Naomi Parker. She stood at a lathe, wearing a light-colored coverall with the sleeves rolled just above her wrists. Her hair was tucked under a polka-dot bandana, and her shoes had thick soles. She leaned forward slightly, both hands steady on the machine.

The photo was published that same year in newspapers across the country. It ran with no name, just a simple caption describing the scene. Naomi saw it and saved a copy. She had been proud of the work and liked how she looked in the picture. There was no reason to believe it would ever become important.

Naomi had taken the job alongside her sister Ada. They lived together in a rented room and shared a daily routine that began before sunrise. Naomi operated machines. Ada worked in the office. Each day, they packed metal tins with simple lunches and walked through the gates as civilian defense workers. Their pay was modest, and the hours were long, but they understood the weight of what they were doing.

Mistaken Identity and the Search for the Truth

For most of her life, Naomi Parker Fraley remained unknown outside her family. The photograph taken at the Alameda Naval Air Station had been archived by the government, like many wartime images. Decades later, when it resurfaced in articles and museum exhibits, it was displayed with someone else’s name beneath it.

That name belonged to Geraldine Hoff Doyle, a Michigan woman who had briefly worked in a factory during the war. She had seen the same photograph in a 1980s magazine and thought it showed her. The media picked up her story and, without verifying the source, began referring to her as the original Rosie the Riveter. Museums followed. Textbooks and newspapers repeated the claim. By the 1990s, Doyle’s name had become attached to the poster in popular memory, even though she had never worked at the Naval Air Station in Alameda.

Naomi saw the image in a 2011 exhibit at the Rosie the Riveter museum in Richmond, California. The label credited Geraldine Doyle. She quietly told a staff member that the photograph showed her, not someone else. She brought documentation. Her sister, Ada, confirmed the same. Still, the correction was not made.

It took several more years before the story reached James Kimble, a communications professor at Seton Hall University. He had been researching wartime propaganda and became curious about the image’s origin. His investigation led him to government archives, newspaper clippings, and finally to Naomi herself. He compared the timelines, employment records, and facial features in other photographs. His conclusion was published in 2016. Naomi Parker Fraley had been the woman in the photograph all along.

When asked how she felt about the discovery, Naomi gave a brief quote: “The women of this country these days need icons. If they think I’m one, I’m happy about that.”

The Woman in the Photo, and Everyone She Stood For

Naomi Parker Fraley passed away in 2018 at the age of 96. By then, the photo of her standing at the lathe in 1942 had become widely circulated, finally credited, and quietly honored.

She spent most of her life out of the spotlight. She worked, married, lived in small towns, and kept the original newspaper clipping of her photograph tucked away. When asked about it late in life, she said she was glad people had come to care. “I was just doing my job,” she told a reporter.

The poster had become a symbol of female empowerment. But for her, it had always just been a photograph of a day at work.

Naomi Parker Fraley in her later years. She was finally recognized as the real woman behind the wartime poster.

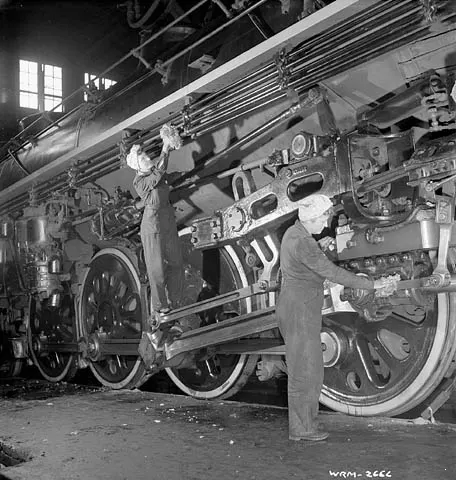

Her story is often told alongside the image, but it also belongs beside many others. The war had opened factory gates to women across the country. They drilled, riveted, sorted, and welded. They stepped into jobs that had previously been denied to them, and they carried production lines that kept the war effort moving.

By the end of the war, most of these women were laid off or asked to return to domestic roles. Some stayed on, quietly. Others never stepped into a factory again. But the photographs remained.

Naomi’s image, once misfiled and mislabeled, now lives on in articles, books, and classroom walls. It stands as a symbol of wartime labor, but also as a reminder that symbols begin with people.

She never called herself Rosie. She never asked to be remembered. But she was part of something much larger than herself, and that part, finally, has her name on it.