Margaret Howe Lovatt grew up with talking animals that never quite left her. A slim book from her mother, about a cat named Miss Kelly who could understand human speech, planted the idea that language might not be exclusive to humans. Decades later, she would say that story “just stuck” with her and never quite stopped feeling possible.

In her early twenties on St Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands, that quiet belief met a real door. Over Christmas 1963, her brother-in-law mentioned a hidden laboratory at the far end of the island where people worked with dolphins. Curious, she drove down a muddy track, reached a cliff, and found a stark white building above the sea.

Gregory Bateson opened the door: tall, tousled, cigarette in hand, already an influential thinker. According to Lovatt, he looked at her and asked, “Why did you come here?” She answered that she had heard about the dolphins and wanted to help. The honesty worked. Bateson let her stay, watch, and write down what she saw.

There were three dolphins. “Peter, Pamela, and Sissy,” she recalled to The Observer years later. Sissy, the largest, dominated. Pamela was timid and easily stressed. Peter was the youngest, playful, and “a bit naughty.” Their pool is connected to the sea through tidal openings. Above, the overhanging structure was built to bring humans closer, literally living on top of another species.

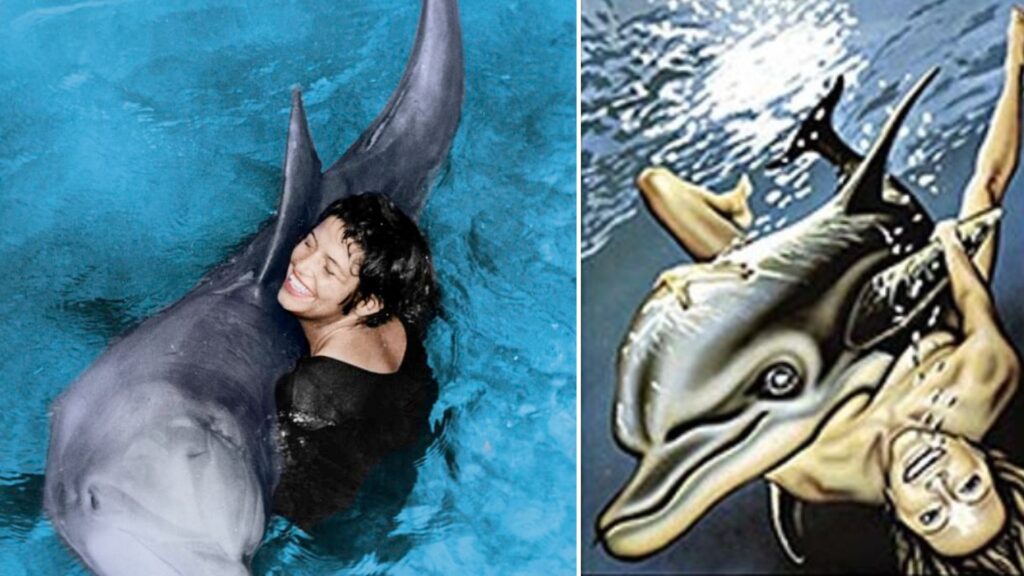

The place existed because of John C. Lilly, a physician and neuroscientist who had become obsessed with cetacean brains after examining a beached whale in 1949. At Marine Studios in Miami, he probed the brains of dolphins and watched them perform tricks for crowds. The size of their cortex convinced him they were not simple show animals, but potential intellectual equals.

Lilly turned that conviction into a narrative. In his book “Man and Dolphin,” he suggested dolphins might learn to mimic human speech. He imagined them one day holding a “cetacean chair” in global decision-making. The language was speculative, but it caught on. Frank Drake later said Lilly’s ideas helped him think about “the challenges of communicating with other intelligent species.”

For astronomers and Cold War agencies, dolphins became a rehearsal for extraterrestrials. Suppose humans could not decode an Earthly non-human intelligence; what hope would NASA or SETI have with signals from deep space? That logic helped secure funding from NASA and the U.S. Navy for Lilly’s new lab in the Caribbean, where science, fantasy, and politics all converged on St Thomas.

When Lovatt stepped into Dolphin House in early 1964, she arrived as an outsider and quietly became indispensable. Bateson focused on dolphin-to-dolphin communication. Lilly moved between donors, conferences, and grand theories. Lovatt stayed at the tanks. She observed, hand-fed, cleaned, listened, and over time became the human presence Peter watched most closely.

The official aim sounded straightforward. They wanted Peter to produce clear, repeatable English words. If he could shape sounds like “Hello Margaret” on cue, Lilly believed it would prove dolphins had the capacity for human-style language and, symbolically, open a door between species. Lovatt began with slow, structured lessons at the waterline, repeating phrases near Peter’s blowhole.

She played with rhythm, pitch, and consonants, exaggerating the “M” in “Margaret.” Audio tapes from the period captured her patience. She later recalled the moment Peter rolled and tried to bubble an “M” through the water, a slight, distorted sound that she treated as hard-earned progress. Others heard noise. She insisted there was intent inside it.

Nights revealed a contradiction. Each evening, the staff pulled down the garage door and drove away, leaving three intelligent animals circling in their pool while the building above went dark. Lovatt felt the gap between the rhetoric of “minds like ours” and the habit of abandoning those minds for twelve quiet hours. It bothered her more than it bothered anyone in charge.

Margaret Howe Lovatt’s NASA experiment to teach a dolphin to talk

Lovatt’s solution was extreme and simple. She proposed flooding the upper floor so she could live there with one dolphin around the clock. She believed that constant proximity, similar to that of a parent with a child, would give Peter a better chance to associate sounds, meaning, and a shared routine. She told John Lilly she wanted to “fill this place with water” and move in.

Lilly agreed. He liked big gestures that sounded revolutionary. The upstairs rooms and balcony were waterproofed and partially filled, transforming the offices into a shallow lagoon that was threaded through desks, cables, and platforms. The plan was to spend six days together inside, and one day out with the other dolphins. It was part research protocol, part inhabiting the fantasy his own book had sold.

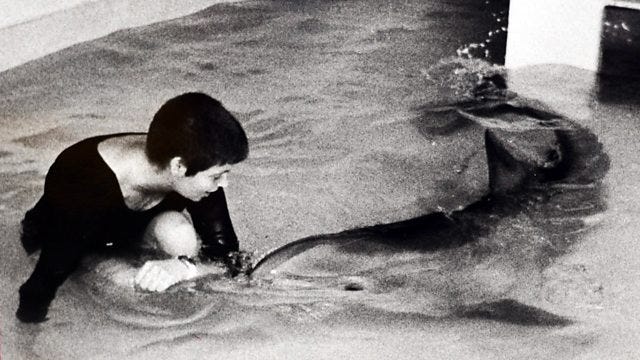

Lovatt chose Peter for the live-in experiment. He had less previous training, an intense fixation on her, and seemed most responsive to her. She set up a bed on a central platform, hung her desk above the water, and accepted a life where sleep, notes, coffee, and conversation all happened within reach of a dolphin who could nudge her awake at any time.

The first nights felt surreal. Outside, people ate dinner and drove home from work. Inside, she lay in half darkness, listening to pumps and watching Peter’s fin cut through moonlit water beside her mattress. She later admitted wondering why she was there, then defaulted to the answer that drove her from the start: to see what might happen if she stayed.

Daily tapes showed her persistence. Twice a day, she drilled sounds, encouraged attempts at “Hello Margaret,” played with phrasing, and logged even small changes. She believed Peter was trying. “He worked on that ‘M’ so hard,” she told the BBC. The work was repetitive, low-key, and dependent on patience rather than breakthroughs.

The deeper education unfolded when they were not formally “doing lessons.” Peter investigated her constantly. If she left her knees in the water, he examined them closely. If she moved through the room, he shadowed her path. She began to think of him less as a laboratory subject and more as a demanding roommate, an alert presence who noticed everything.

Visitors arrived with high expectations. Carl Sagan and others from the early SETI circle viewed Dolphin House as a small-scale model for alien contact. Drake later suggested experiments where trained dolphins would pass information to untrained ones, testing whether they had a structured communication system. In practice, Lilly did not build those trials. He focused on the cleaner story of English lessons.

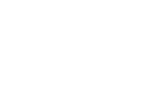

The reality that kept intruding was Peter’s body. He was an adolescent male in confinement with one constant human. In the narrowed world of the flooded rooms, his sexual arousal was frequent and prominent. At first, Lovatt had him taken downstairs to the two female dolphins to release that energy. Still, the transfers were chaotic and broke the fragile rhythm of teaching.

How the dolphin sex controversy overshadowed John Lilly’s research

Margaret later described the turning point plainly. Rather than repeatedly stopping everything and moving him, she began manually relieving his arousal in the tank so they could “get rid of that” and continue. She told The Guardian it was “sexual on his part, not sexual on mine, sensuous perhaps.” Her framing saw it as pragmatic, part of managing Peter.

Crucially, this did not happen in secret. Staff saw it from the walkways. There were no curtains. Lovatt believed this transparency proved it was not a sordid affair, but a practical response inside an already unconventional experiment. She also thought it deepened Peter’s trust, because she no longer sent him away whenever his body interrupted their schedule.

Outside that narrow context, the choice read very differently. The boundary between research and intimacy was blurred in a way that critics later deemed unforgivable. It gave every future retelling an easy hook: the woman who sexually serviced a dolphin in a NASA-related lab. Whatever Lovatt felt at the time, that detail would eventually eclipse almost everything else.

The most brutal version appeared in Hustler magazine in the late 1970s, under the banner of “interspecies sex.” Lovatt recalled finding a copy and seeing her name, Peter’s name, and an explicit illustration. She bought every issue she could reach, but the story now existed as pornographic folklore. It flattened her own words into a spectacle built for sniggering readers.

Tabloids and later clickbait would run with that version. It transformed a complex research setting into a spectacle, overlooking the fact that the exact location had been sold years earlier as part of a serious NASA-funded project aimed at bridging the gap between humans and another intelligent species. Once “dolphin sex” was attached to Margaret Howe Lovatt, it never really detached.

Meanwhile, John Lilly’s other obsession unfolded in the background. He held government permission to use LSD in controlled settings and was fascinated by its potential to change consciousness. Friends, including Ric O’Barry and Jeff Bridges, later described how Lilly shifted from white coat scientist to someone far more interested in internal voyages and mystical speculation than in reproducible results.

Lilly began injecting some dolphins with LSD, curious whether the drug would provoke new vocalizations or behaviors. It did not deliver what he hoped. According to Lovatt and others, the dolphins showed no apparent, dramatic change that matched his grand ideas. The trials still happened, though, and highlighted how casually extreme interventions were made on highly sentient animals.

Lovatt objected to giving LSD to Peter and said Lilly agreed to spare him. It was Lilly’s lab and Lilly’s funding, and she could not stop him from using the drug on Sissy and Pamela. Those injections sharpened the ethical discomfort already present in a project that combined invasive neurology, confinement, and intimate contact in the name of speculative communication.

By autumn 1966, Lilly’s attention had drifted toward psychedelics and increasingly esoteric theories. The slow grind of vowel drills and taped attempts no longer interested him the way LSD did. Funding agencies, already uneasy with the lab’s direction and results, began to withdraw their support. Gregory Bateson left, unhappy with Lilly’s choices and the conditions for the dolphins.

Without solid backing, Dolphin House would not be able to survive. The flooded rooms that had become Lovatt’s world were marked for shutdown. The three dolphins would be moved to Lilly’s remaining facility. In this converted Miami bank, small indoor tanks replaced the open-sea pool of St. Thomas. Lovatt did not make that decision. She was told to help dismantle what she had built.

She had spent months living eye to eye with Peter, treating him as partner, student, problem, and, in her own view, friend. Now, the lab that enabled that closeness was closing its doors and boxing him up. What happened to Peter next, in that dark bank vault of a lab, would turn an odd story into something far more troubling.

The dolphins left St Thomas in crates instead of tides. Lovatt watched preparations for shipment to John Lilly’s remaining facility in Miami, a former bank building with small indoor tanks that felt nothing like the open sea pool she had filled with light and sound.

She later said quietly that if Peter had been a dog or a cat, she might have tried to keep him. Instead, her role shifted from live-in partner to someone packing up animals she understood better than the people signing the papers.

Miami meant shallow rectangles, artificial lighting, recycled water, and a lack of a Caribbean sky. Accounts from those who visited describe an antiseptic space that stripped away the sensory richness Dolphin House had offered. Within weeks, Peter’s behavior underwent a significant change. He moved less, responded less, and no longer had the constant human presence that had structured his days.

Then Lilly phoned her. Lovatt recalled him saying that Peter had “committed suicide,” that he had sunk to the bottom and not come up for air. For most land mammals, that phrase would be a metaphor. For dolphins, who must choose each breath, it sounded uncomfortably literal.

Dolphin advocate Ric O’Barry later explained that every inhalation for a dolphin is deliberate. In his words, if life becomes too much, a dolphin can simply not take the next breath. It is a biological possibility that indicates intent when a healthy, young animal stops swimming upward.

Veterinarian Andy Williamson, who knew the St Thomas animals, framed Peter’s death as emotional. He suggested the move had broken a bond Peter did not understand, that separation and confinement created a kind of grief his physiology could enforce with a single choice underwater. It sounded less like science and more like an accusation.

Lovatt’s reaction was complicated. She said she felt more pain imagining him in that bank building than knowing he was gone. In her view, death released him from conditions that never should have replaced the sea. The guilt sat between those lines, never fully claimed, never entirely denied.

Lilly did not rebuild Dolphin House. In the following years, he moved deeper into psychedelic exploration, sensory deprivation tanks, and ideas that drifted from empirical work toward mystical speculation. Former colleagues and historians describe a trajectory in which the disciplined researcher gave way to the psychonaut. At the same time, the dolphins that anchored his fame slipped into footnotes.

John Lilly’s LSD obsession and the downfall of Dolphin House

The public story, however, refused to stay in footnotes. Hustler’s cartoonish spread fixed Margaret Howe Lovatt and Peter inside a sexual punchline. Sensational coverage in tabloids and later online pieces repeated the same frame: the woman who had sex with a dolphin in a NASA experiment. The complexities of power, protocol, and design rarely survived the headline.

When Christopher Riley’s BBC documentary “The Girl Who Talked to Dolphins” aired, it gave Lovatt space to answer in her own voice. She repeated that what happened with Peter felt pragmatic, that she did not see herself as a fetishist in a tank. She also admitted that the Hustler portrayal hurt, then said she tried to ignore it.

Parallel cases began to surface in the media cycle. Malcolm Brenner publicly discussed his own claimed sexual relationship with a dolphin named Dolly in the 1970s, and commentators folded his narrative beside Lovatt’s as if they belonged to the same file. For many readers, “dolphin sex” became a clickable category rather than a sign of failed ethics.

Researchers who came after treated the St Thomas experiment as an example of how enthusiasm can outrun evidence. Advances in animal communication studies pointed out that expecting dolphins to form English words with their anatomy made little biological sense. Some, including scientists at the SETI Institute, shifted the question toward decoding the complexity of dolphin signals on their own terms.

Within that reassessment, one part of Lilly’s original instinct survived. Studies of dolphin vocalizations and social structures have reinforced that they hold sophisticated, layered communication systems. The idea that we share the planet with other intelligent minds no longer relies on forcing human syllables through a blowhole. It rests instead on accepting intelligence that does not mirror ours.

Margaret Howe Lovatt stayed on St Thomas. She married a photographer who had documented the project, moved back into the empty Dolphin House, and raised three daughters in rooms where water once reached the furniture. In later interviews, she described the building as evoking a “good feeling,” as if the failed experiment had left behind something gentler than its reputation would suggest.

Letters reached her from young researchers who had grown up on fragments of her story. Some said that reading about a woman living with a dolphin had inspired them to pursue a career in marine biology. She liked that thought, and once compared Peter’s role in their lives to Miss Kelly’s role in hers: a story that made another kind of mind feel close enough to try and reach.

If this story fascinated you, don’t miss our feature on the Monster Study, where researchers in 1939 deliberately induced stuttering in orphans to test language development.