War stories love that moment when a lone soldier slips into an occupied city, fools an entire garrison, and walks out at dawn as the unexpected hero. Most films treat that as fantasy. In April 1945, in the Dutch city of Zwolle, one man actually did it. His name was Léo Major.

He was not a commando or an officer with tailored uniforms. He was a thin French Canadian from a rough part of Montreal, the first of thirteen children, raised by a father who was hard on everyone and sometimes crossed the line. At nineteen, he joined the Canadian army. He said it was partly for the thrill and partly to show his father he could be worth something.

He had been born in the United States. Léo was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to French Canadian parents, and they returned to Montreal before he turned one. That city shaped him. It was where he boxed, worked small jobs, and finally stepped into a recruiting office in 1940 to enlist in the Régiment de la Chaudière.

By the time his regiment landed on Juno Beach on D Day, June 6, 1944, Major was working as a scout and sniper. He carried a stubborn streak that came from years of refusing to accept limits. It would matter more than any instruction he ever received.

Who was Léo Major before he became the one eyed ghost

On D Day, he joined a reconnaissance push inland. He moved ahead of the main force and found a German halftrack with its crew still nearby. Instead of waving for help or waiting for a larger unit, he closed in alone, killed the soldiers, and took the vehicle. Inside, he found communications equipment and code sheets that intelligence officers treated as rare finds.

A few days later, he encountered his first patrol of Waffen SS. There was no pause. He opened fire and killed four of them, and one of the dying men set off a phosphorus grenade. The blast cut across his face and cost him the sight in one eye. At a field hospital, a doctor told him his time on the line was over.

Major would not accept that verdict. A sniper needs one good eye, he told the medical staff, and he still had one. He put on an eye patch, joked that he looked like a pirate, and returned to his regiment as a scout. It was the start of a reputation among his peers. He did not scare easily, and he did not always follow the expected line.

In the autumn of 1944, the First Canadian Army was given a grim assignment. The Scheldt estuary in the southern Netherlands and northern Belgium had to be cleared of German forces so Allied supply ships could reach Antwerp. The ground was low, wet, and open. German units had spent months digging in. Casualties rose quickly.

During that campaign, Major became a figure of near myth within his regiment. He was sent to learn what had happened to a Canadian company that had vanished during the fighting. Moving alone through dikes and narrow canals, he found abandoned gear and understood the men had been captured. Trying to get out of the cold, he slipped into a small house and saw two German soldiers on a nearby dike.

He captured the first German and used him to draw the second one closer. When the second soldier tried to lift his weapon, Major shot him. He then marched his prisoner straight to the local German commander, stepped into the position as if he belonged there, and demanded their surrender. Comrades and later historians wrote that the entire company, roughly a hundred men, handed themselves over.

On the return trip, SS troops saw Germans walking under guard and opened fire on their own men. Several were killed, and others were hit. Major kept moving his line of prisoners toward Canadian positions and did not slow for the incoming fire. He stopped only long enough to wave down a Canadian tank and instruct the crew to take up the SS position behind him. Ninety-three prisoners reached the Canadian front that day.

How did he capture ninety three German soldiers by himself

The incident grew into a lasting story about Major being offered the Distinguished Conduct Medal and turning it down because he disliked British General Bernard Montgomery. Over the years, the tale hardened. Later checks in military archives revealed a DCM recommendation from 1945, but nothing earlier, and some Dutch historians question certain aspects of the refusal tale. What no one disputes is that his fellow soldiers saw one man walk back from the fighting with almost a hundred enemy troops behind him.

Only a few months later, in early 1945, Major’s run of fortune seemed to end. Near the German-Dutch border, while searching for missing British soldiers, the vehicle he was riding in hit a land mine. The blast threw him into the air and slammed him back to the ground. He broke vertebrae, an arm, ribs, and both ankles, and was taken to a field hospital, where he was kept on morphine to manage the pain.

Doctors told him he was finished for the rest of the war. For nearly a week, he stayed in bed and listened to the slow routines of a ward filled with men who knew they would not return to the front. Then he made up his mind that he would not stay. When a chance appeared, he slipped out, caught a ride in a jeep, and headed for Nijmegen, where he knew a Dutch family. He stayed with them for almost a month and then limped back to his regiment in March 1945.

What pushed one soldier to liberate an entire city alone

By April, his unit had reached the outskirts of Zwolle. The city, with about fifty thousand residents, remained in German hands. Canadian planners were ready to shell it hard to break the defense. That plan risked killing civilians and destroying much of the town. Before giving the order, the commanding officer asked for volunteers to scout the defenses and, if possible, contact the resistance.

Private Léo Major and his close friend Corporal Willie Arseneault stepped forward. Their assignment was simple on paper. They were to watch and report what they found. Among themselves, they agreed that if there was any chance to save Zwolle from an artillery strike, they would try something more.

They entered Zwolle after dark on April 13, 1945. They moved along the edge of the city until a German position spotted them. Gunfire erupted. Arseneault was killed instantly, and Major saw him drop in the street. Furious, he shot the men who had fired on them. The rest of the Germans climbed into a vehicle and sped off into the night.

He had a decision to make. The mission had been blown, and his friend was dead. He could fall back and report, or he could keep going. He chose to continue alone. What happened next became the source of his nickname, the One-Eyed Ghost, and later drew comparisons to a real-life action figure.

Near the outskirts, he stopped a German staff car and ordered the driver to take him to an officer who was drinking in a bar. The officer spoke French. Major told him in an even voice that Canadian guns would begin shelling Zwolle at six in the morning. If German troops stayed, they would bring casualties on themselves and on civilians. If they withdrew, they might save the town. As a gesture of trust, he let the officer keep his sidearm.

His bluff needed noise. Through the rest of the night, he raced through the streets, firing his weapon, throwing grenades into empty corners, breaking windows, and shouting to create the sound of a much larger force. Under the cover of darkness, he ambushed small groups of German soldiers, disarmed them, and marched them to Canadian positions outside the city.

He did it several times. Groups of eight to ten men were walked out, handed over to troops waiting along the outskirts, and he went straight back in. He was a thin and worn soldier with one good eye and a machine gun, yet to German sentries listening to gunfire in different parts of town, he sounded like a full assault.

Zwolle’s resistance members still had no clear idea what was unfolding. At some point before dawn, he reached a few locals, explained what he was trying to do, and kept moving. Between bursts of fighting, he slipped into houses, took quick naps on couches or beds, then forced himself back into the streets for another round.

During the night, he found the Gestapo headquarters and set it on fire. Later, he discovered the SS office. There, he fought at close range with senior officers. Several were killed, and the rest scattered into the dark. Among the bodies, he saw two men wearing resistance armbands. They had been posing as local fighters, a sign that the underground had already been infiltrated or would have been in the coming days.

By about 4:30 in the morning, the gunfire stopped, answering him. Patrol routes were empty. German troops had crossed the nearby river and left the city behind. When he finally met members of the resistance in person, he told them the Germans were gone and Zwolle was free.

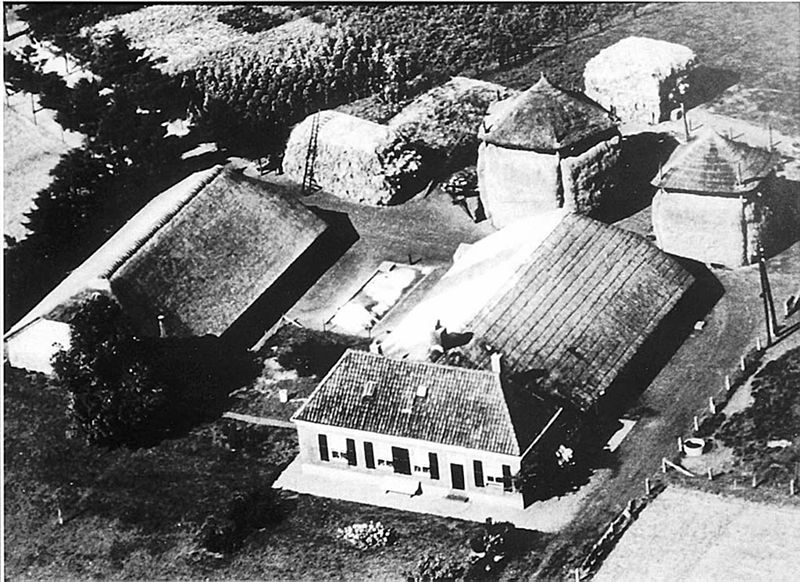

At dawn, Canadian troops advanced, expecting a fight, and found none. The planned artillery barrage was cancelled. Civilians stepped into the streets and learned their town had been freed during a single confused night. Major, who had spent hours running, shooting, shouting, and marching prisoners, reached his unit around nine in the morning. He then returned to recover the body of Willie Arseneault. He had it taken to a nearby farm until it could be buried.

For that night of work, he received the Distinguished Conduct Medal, one of the highest awards for gallantry available to a non-commissioned soldier in the Commonwealth. It was the first of two he would earn.

After the war, he left the army, and the transition into civilian life brought its own weight. Quebec society carried mixed feelings about the conflict. Conscription had caused hard divisions, and many French-speaking soldiers who fought in Europe did not return to celebrations. Several came home quietly and stayed that way.

Major did the same. At thirty, he was back in Montreal, living on a veteran’s pension and managing the aches of old injuries. He listened to James Brown, sewed clothes, and rarely spoke about his experiences in Europe. The legend of the fearless scout was only part of who he was. Friends and relatives recalled how he carried memories of shooting teenage soldiers through a sniper scope, and how war films could bring him to tears.

When the Korean War began, he enlisted again. This time he served with the Royal 22e Régiment, often known as the Van Doos, and once again fought in terrain where a single hill could shape the fate of thousands.

In 1951, United Nations forces, including a United States infantry division of roughly ten thousand men, came under repeated attacks by Chinese troops estimated at four times that number. A key hill changed hands more than once, and at one stage, Chinese units threatened to surround American formations from the high ground.

Major was placed in command of an elite reconnaissance and sniper platoon. With eighteen men, he received orders to retake a hill that other units had tried and failed to hold. They moved up after dark, crawling through ravines and low brush and navigating by memory until they found themselves inside Chinese positions.

At his signal, the group opened fire from the centre of the enemy line. Confusion spread quickly as gunfire and bursts from machine guns came from a place the defenders considered secure. By a quarter to one in the morning, Major’s small platoon had taken the hill.

Higher headquarters soon instructed him to leave the position in advance of expected counterattacks. He refused. He gathered what cover he could find for his men and prepared to hold. Over the next three days, they survived artillery fire, small arms fire, and repeated attempts by Chinese forces to reclaim the height.

When reinforcements reached them, the hill was still in United Nations hands. For leading the assault and defending the position under heavy pressure, Major received a bar to his Distinguished Conduct Medal, marking that he had earned the same award twice in separate wars. Remarkably few soldiers in the Commonwealth ever achieved that distinction. He was the only Canadian.

Back home in Quebec, he remained largely unknown outside military circles and the Dutch city he had helped liberate. He never wrote a memoir, and he did not tour veterans’ halls giving speeches. He spent his time with family, lived with his injuries, and treated them as the cost of coming back.

The story of Zwolle might have stayed a local memory in the Netherlands if not for a knock on his door in 1969. A delegation from Zwolle had come to Montreal to invite him to a ceremony marking the liberation of the city. When they reached his home, his wife and children were surprised to see how strongly people from another country remembered the quiet man with the eye patch sitting in their living room.

That visit marked the beginning of a slow climb toward recognition. Zwolle named a street after him and held annual events in his honour. Dutch veterans and soccer supporters lifted banners with his young face on them. Years later, Canadian reporters returned to the story. A French-language documentary called “The One Eyed Ghost” aired on Radio-Canada and introduced him to viewers who had never heard of a soldier who once treated occupied streets as his own territory.

Why his actions in Korea made him a rare military figure

Historians and curators at military museums followed his record, spoke with surviving comrades and relatives, and worked to sort legend from fact. They found repeated examples of boldness and stubborn independence. He had refused orders he considered wrong or too cautious. He had rarely spoken about his medals. He did not fit neatly into the official image of a war hero and never tried to.

Léo Major died on October 12, 2008, in Candiac, Quebec, at the age of eighty-seven. A Dutch colonel attended his funeral, a quiet sign of the bond between a Canadian soldier and a European city that had never forgotten him. He was laid to rest in the National Field of Honour, another veteran among veterans, his campaigns carved into the stone above him.

If you remove the uniforms and the dates, his story follows a simple line. A poor boy leaves home trying to prove himself to a father who rarely gave him credit, loses an eye and nearly his spine, fights through two large wars, and again and again moves toward danger when others are told to hold back. He did not liberate Zwolle because a superior ordered it. He did it because he stood in the dark with a friend dead at his feet and a city full of civilians ahead of him and chose not to walk away.

On the page, he was listed as an infantry sergeant, another name in the lists from Normandy, Zeeland, Zwolle, and Korea. In life, he was far harder to label. Ordinary in upbringing and remarkable in his decisions, he was the kind of madlad who existed long before the internet thought to invent a word for one.

You can also explore the story of Deborah Scaling Kiley, who survived a shark filled shipwreck only to face a strange end later, and the life of Audrey Hepburn, whose path from surviving World War II to winning an Oscar was far more complex than her elegant image.

Sources

- Léo Major profile, The New York Times

- Medium feature on Léo Major, Medium

- Léo Major entry, Wikipedia