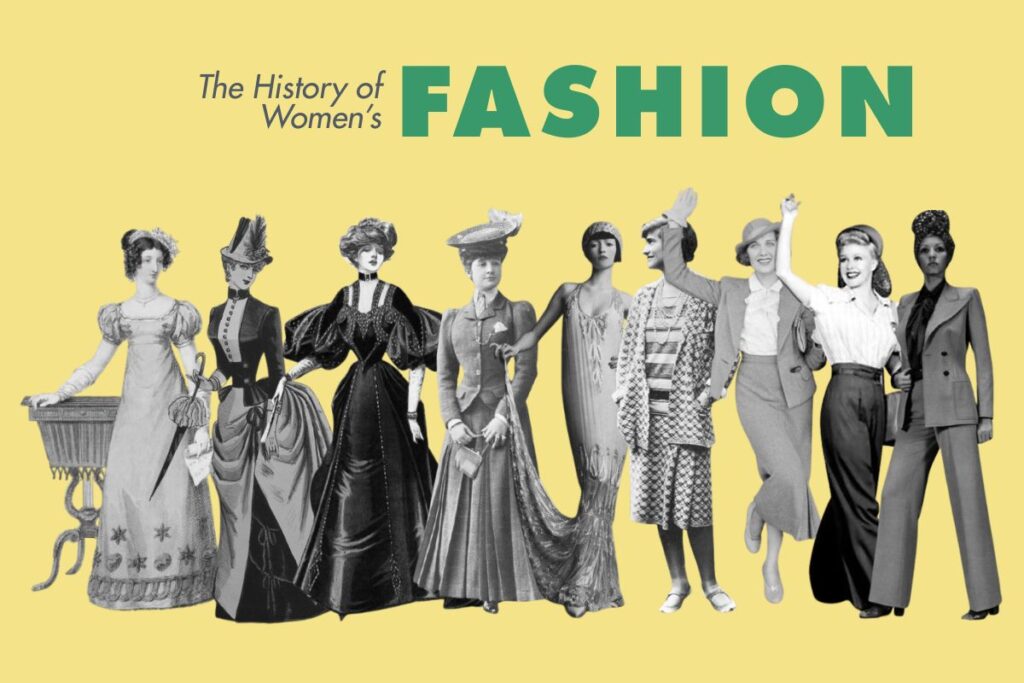

In 18th-century Europe, fashion became a spectacle. Skirts widened so much that women had to turn sideways just to pass through a door. These exaggerated shapes came from panniers, hidden structures sewn beneath the dress to push the fabric out sideways, not unlike table wings. The point was to signal control, not offer comfort. If you wore one, you likely didn’t have to do anything else with your day.

Fabrics turned sugary. Pastel silks, ribbons, and lace layered into confections. The French queen Marie Antoinette set the tone with her constantly changing wardrobe and trend-setting gowns. Her robe à la polonaise lifted the back of the dress into gathered swags, adding even more volume. This kind of styling took time, money, and a team of dressers. Every fold meant privilege.

By the 1790s, the extravagance came to a halt. The French Revolution made that kind of fashion a political liability. Panniers disappeared and corsets began to loosen. Women began wearing gowns inspired by classical statues, with light fabrics and high waistlines. Dressing simply was no longer a peasant thing; it became radical.

High Waist, Light Fabric, Low Stress

Early 1800s fashion looked soft and minimal, especially compared to what came before. Women now wore Empire-waist dresses that cut just under the bust and flowed straight down to the floor. The shape echoed Roman and Greek sculptures. These gowns were often made from muslin and had very little structure. For a brief window of time, women wore what actually felt good.

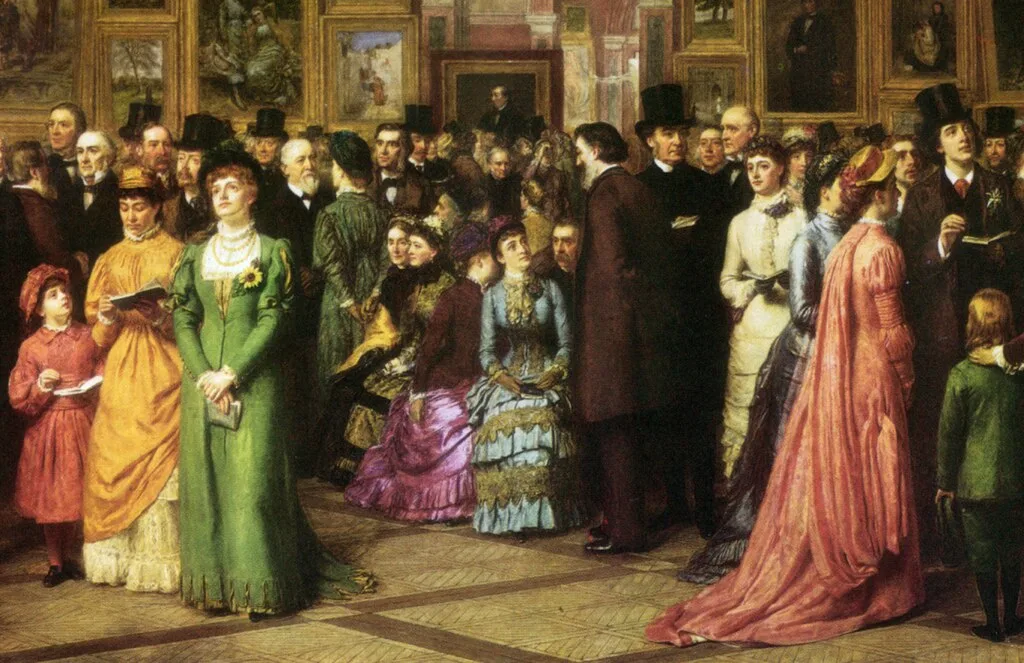

The simplicity did not last long. The Victorian era swept in with new rules. Sleeves expanded, necklines rose, skirts grew heavier, petticoats multiplied, and corsets returned. This time, they reshaped more than the waist. They pushed the chest forward and the hips back, forming what was known as the S-curve silhouette.

As the 19th century continued, skirts became engineering projects. The crinoline arrived, essentially a steel cage that women wore under their dresses. It created massive bell shapes that turned every entrance into a performance. While the outside looked light and elegant, the inside felt like scaffolding.

Dressing Like a Machine

Factories changed fashion forever. With the invention of the sewing machine, clothes no longer had to be handmade. Fashion magazines, dress patterns, and department stores turned once-exclusive styles into everyday options. By the late 1800s, women could buy versions of what society women wore. Just not the comfort.

Every few years, the silhouette changed again as bustles popped out behind the skirt, sleeves swelled at the shoulders, and skirts rose, dipped, and rose again. But the core idea stayed the same: shaping the body into whatever structure was in style. Through force rather than flexibility.

Meanwhile, women were moving both physically and socially. As the suffrage movement gained momentum, so did the popularity of practical outfits. The “suffragette suit” paired tailored jackets with walking skirts, signaling both political intent and physical freedom. Women were taking to the streets, and for once, their clothes were designed to let them.

When Hemlines Started Talking Back

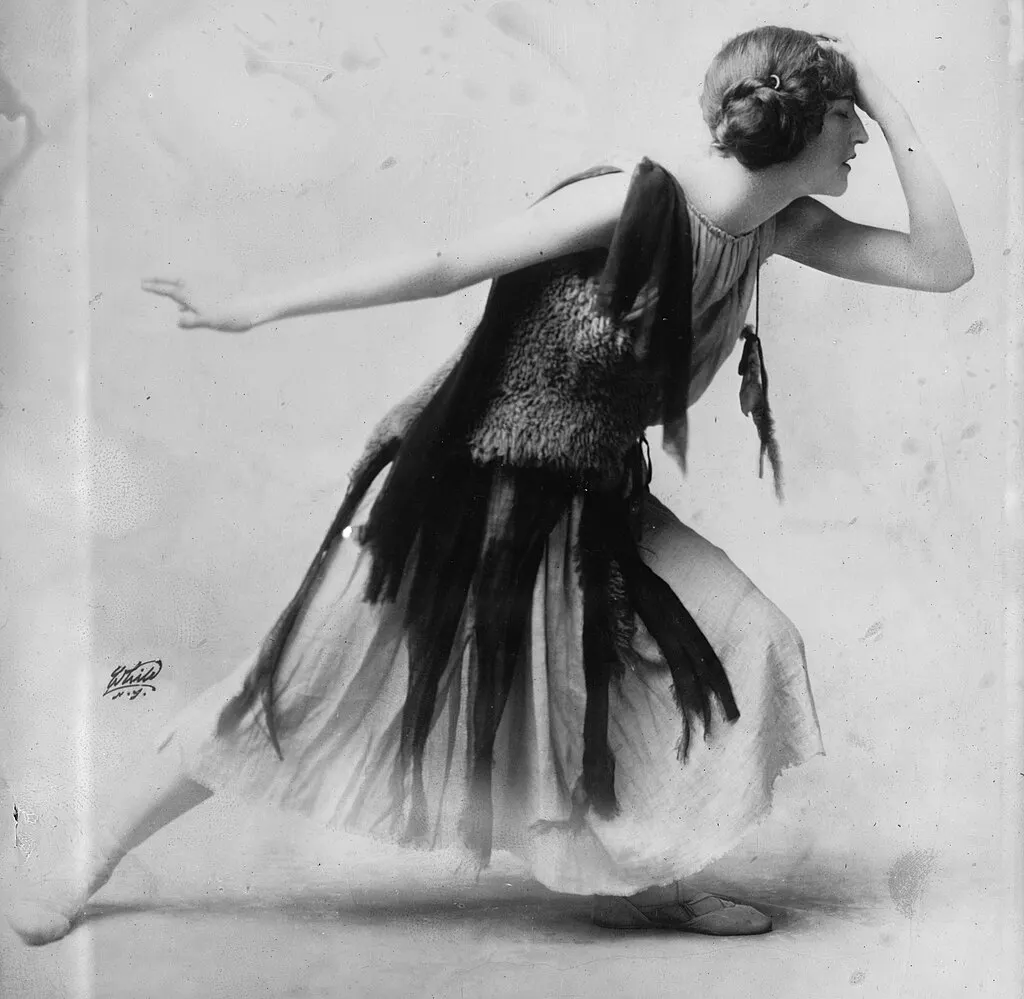

By the 1920s, women had had enough, and after the trauma of World War I, fashion shed its weight as hemlines rose to the knee, waists dropped low, and sleeves disappeared. For the first time, women dressed like they did not owe anyone elegance. The flapper look took over cities. Loose dresses, cloche hats, and bobbed hair signaled freedom from both corsets and expectations.

The dresses did more than show skin because they allowed movement. Dance halls filled with women in fringe, beads, and sequins, shaking loose every inch of constraint. These were more than fashion choices; they were public declarations of independence. Women smoked, drank, and voted, and their outfits reflected the shift.

But the party didn’t last forever. The Great Depression arrived in the 1930s, dragging fashion back into restraint. Silhouettes lengthened again and fabric became precious. Details like ruffles and collars returned, carefully stitched to make the most of limited materials. Style still mattered, but now it had to stretch.

War Makes the Waistline Work

During World War II, fabric was rationed and so was patience. Women entered the workforce in huge numbers, filling factory jobs, offices, and fields. Fashion followed function as skirts narrowed, shoulders squared, and military-inspired jackets and utility dresses became the norm. It was less about looking good and more about getting things done.

But after the war ended, everything flipped. In 1947, designer Christian Dior introduced what he called the New Look. It brought back full skirts, tiny waists, and soft femininity. The silhouette was round, curved, and carefully constructed. After years of rations and uniforms, women were once again expected to perform beauty.

The change was not subtle. Dior’s designs used layers of fabric, padding, corsetry, and stitching to create an hourglass shape from scratch. It was a cultural reset. Men were home from war. Women were pushed out of jobs. And fashion politely told them where they now belonged.

Pants? In Public?

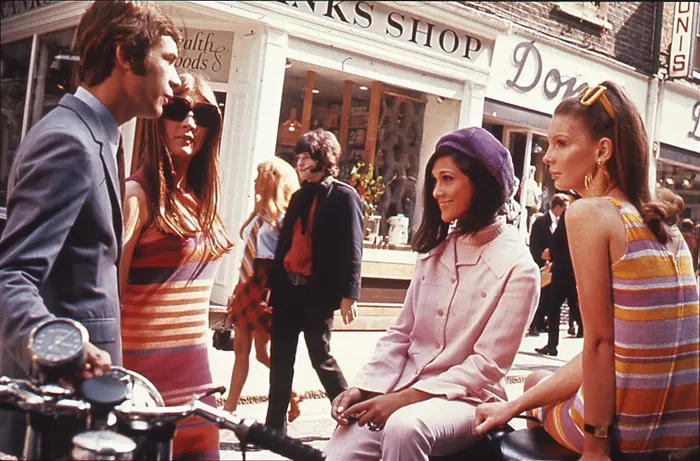

In the 1960s and 70s, rebellion came in waves. The youth questioned everything, including what counted as appropriate clothing. Women began wearing pants outside of work, sparking real controversy. Jeans, once reserved for laborers, became statements of independence. The rules about what a woman could wear were crumbling.

Miniskirts, crop tops, and unstructured silhouettes dominated. Fashion became more personal. Instead of following one trend, women explored identities as hippies wore flowing layers, activists wore sharp tailoring, and disco brought sequins and jumpsuits. For the first time, clothing no longer followed a single set of rules. It followed you.

And designers took notes. High fashion began to reflect the street. Youth culture drove what ended up on runways. Fashion was no longer top-down, but it became inside-out.

Power Shoulders and Plastic Glam

The 1980s were not subtle. Women entered corporate offices in growing numbers, and fashion bulked up to match. Blazers came with shoulder pads, skirts were sharp and structured, colors clashed, and prints screamed. The goal was to look powerful without saying a word. The silhouette was not soft, but it was squared off and hard to ignore.

At the same time, pop stars led a different kind of revolution. Madonna’s layered lingerie-as-outerwear look turned bras and corsets into bold statements. Hair got higher, accessories piled on, and everything glittered, bounced, or made noise. Fashion became a performance.

And underneath it all was plastic. Synthetic fabrics, flashy finishes, and cheap materials created a look that was both shiny and disposable. Power dressing was about visibility. It was about presence, more than comfort or taste.

Less Fabric, More Choice

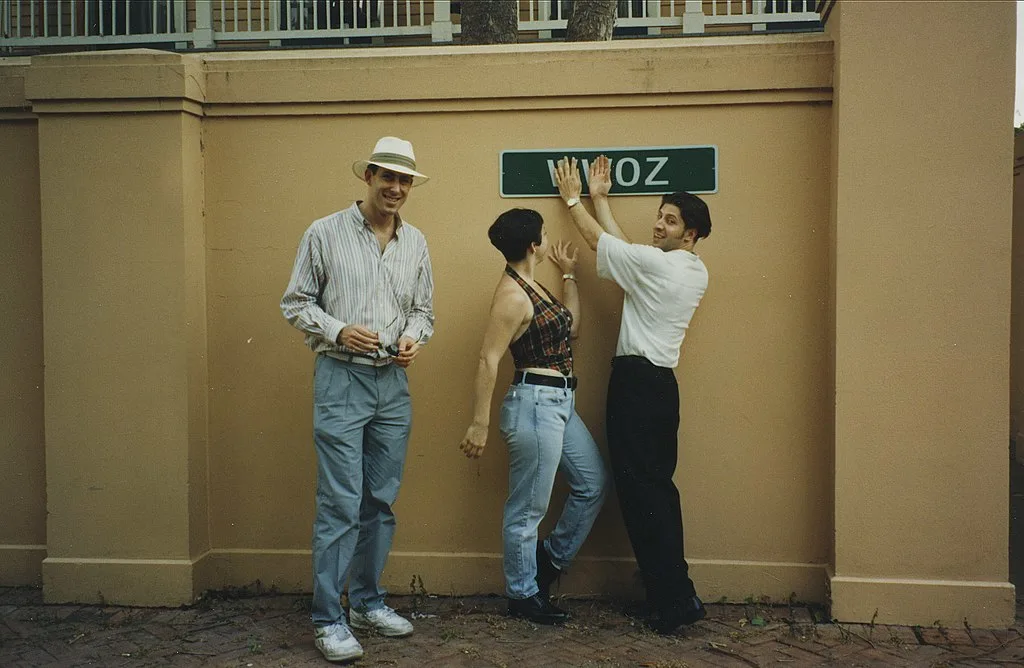

In the 1990s, women’s fashion split in two. One half leaned into minimalism. Think slip dresses, clean lines, and almost no makeup. It was sleek and understated. The other half embraced maximalism again, this time in streetwear. Oversized jeans, crop tops, sports jerseys, and sneakers showed up in closets across cultures.

This duality reflected the larger moment. The fashion world had become global, and style references crossed borders and genres. One woman might wear a Calvin Klein dress on Monday and a Tommy Hilfiger hoodie on Friday. Clothing no longer had to prove womanhood. It just had to express it.

The rules were off the table. Fashion flipped between polished and undone, luxury and thrift, feminine and androgynous. And for the first time, you could wear almost anything and call it fashion.

Threads of the Present

Today’s fashion is less about a single look and more about a shifting mix of identities. You might see a corset paired with cargo pants, a lehenga reimagined as a two-piece set, and a blazer styled over a hoodie. Fashion now talks to the past, the future, and the algorithm. It borrows, flips meanings, and recycles, sometimes literally.

Social media changed how trends spread. You do not need a designer to go viral. A girl in her bedroom can spark a global look. At the same time, people are asking harder questions about where clothes come from, how they’re made, and who gets left out of the industry’s vision of beauty.

Diversity has become a demand, not just a buzzword. From plus-size runways to gender-fluid collections, today’s fashion refuses to be boxed in. It might be chaotic and confusing, but it belongs to everyone.