Long before hospitals and pharmacies, people used whatever they could gather, grind, boil, or swallow to feel better. Some of these cures came from close observation of the natural world, others from traditions passed down through generations, and many from pure invention. Healing was often tied to ritual and belief, guided by the stars, or linked to the rhythms of nature and spirit. A root brewed into a tonic, a whispered charm in the dark, or the movement of the moon could all serve as medicine.

People placed enormous trust in these remedies, sometimes with the same devotion they gave to religion. The body was seen as more than flesh and bone. It was thought to be shaped by invisible forces, bound up with emotions, memory, and unseen spirits. To heal meant not only treating the body but also restoring meaning and balance. For centuries, the problem of human suffering was met with ceremonies, symbols, and stories long before science introduced its own explanations.

The Body as a Battlefield of Spirits

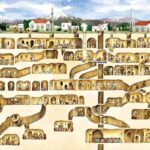

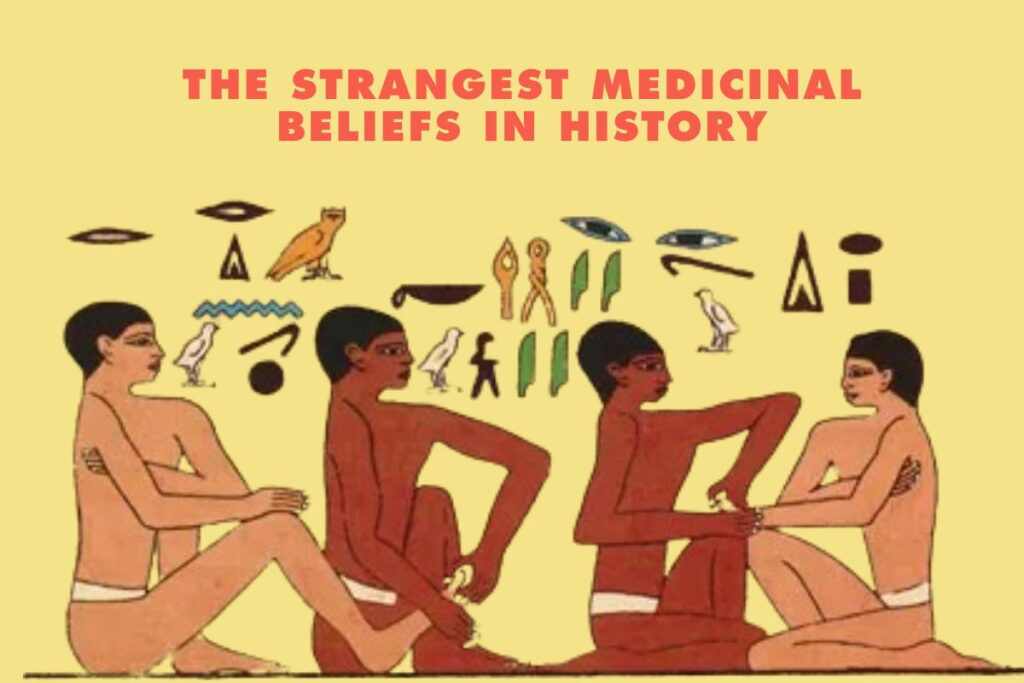

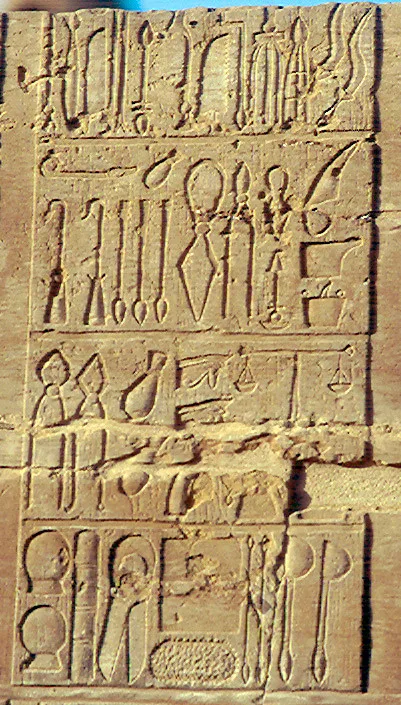

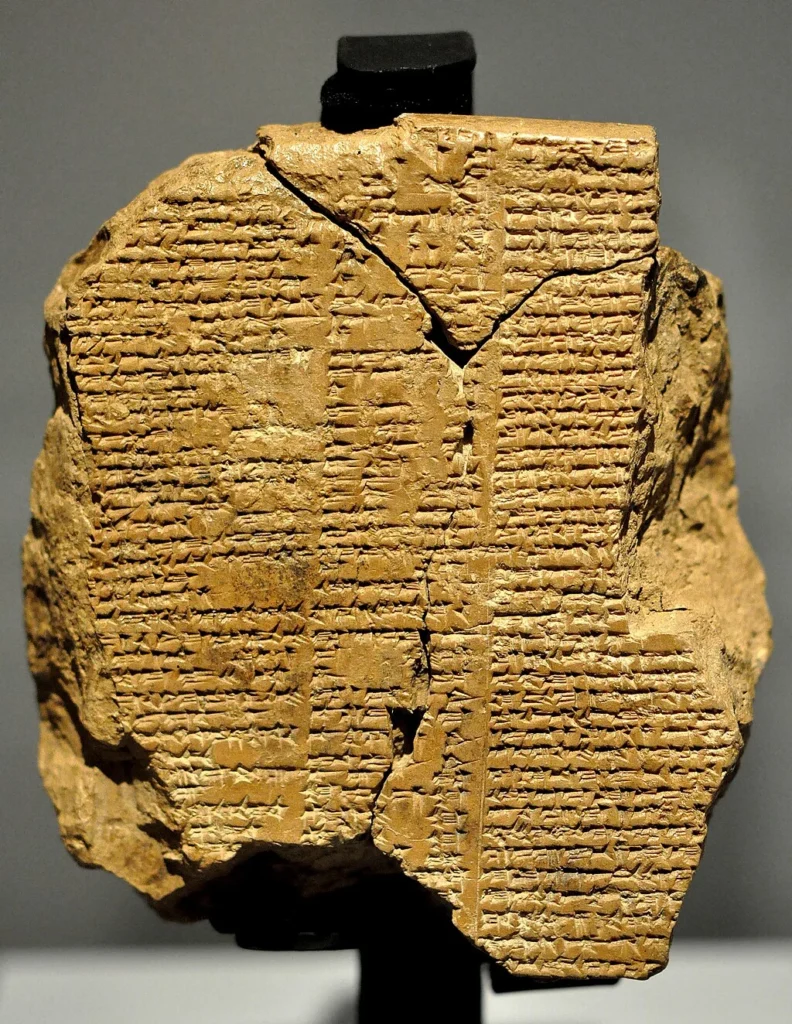

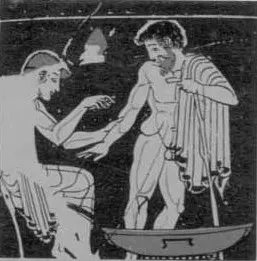

In the earliest civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, illness was often viewed as punishment from gods or as the work of demons that entered the body. Healing rituals involved chants, offerings, and sacred gestures. Words carried weight, and so did crushed plants and brewed mixtures. Clay tablets describe spells used to drive out tooth demons, paired with poultices made of herbs and beer. Practical treatment and spiritual ritual were inseparable.

Priests and physicians often shared the same role, moving between temple and home with equal authority. Medicine and magic were not separate ideas but part of a single system of belief. Healing was a form of faith, and that faith created a framework people trusted, shaping practices from the grand halls of temples to ordinary households.

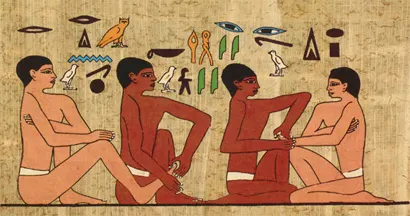

In ancient Egypt, medical knowledge was written on scrolls that treated the body like a sacred map. Each organ was thought to hold meaning: the liver spoke to the stomach, the heart to the bowels, and the breath carried messages from the gods themselves.

Remedies reflected this union of the physical and the symbolic. Mixtures included cow dung, beetle dust, and crocodile fat, combined with ritual instructions to restore balance. Every ingredient had a place in the cosmic order, and healing meant bringing the body back into harmony with the universe.

Greek Theories and Four Humors

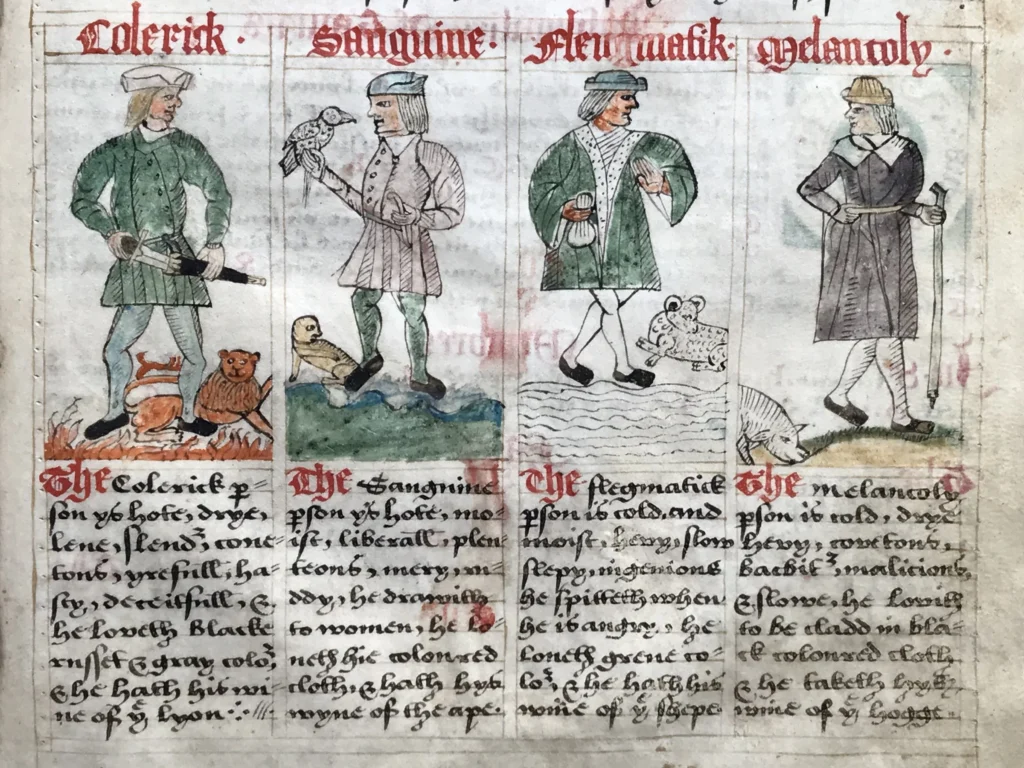

When Greek medicine took root, it introduced ideas that would shape healing for nearly two thousand years. Hippocrates taught that the body carried four vital fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Health, he said, depended on keeping these humors in balance.

Every illness pointed to an excess or shortage. Too much black bile explained melancholy, and physicians prescribed purging. A fever meant the body had overheated, so cooling foods or bloodletting were used to bring the system back into harmony.

Doctors spread these theories across empires. They treated the body as a whole. Bloodletting could calm moods, while cold herbs and hot baths worked to correct inner shifts. Patients were often told to rest for weeks in the clean air of mountains, where nature itself was considered medicine.

Treatments could be elaborate. Some doctors mixed crushed pearls into wine, while others made plasters with goat’s milk and barley. Each prescription returned to the same belief: the body’s inner forces had to move in rhythm, and disorder was the root of disease.

Body and Soul in Medieval Medicine

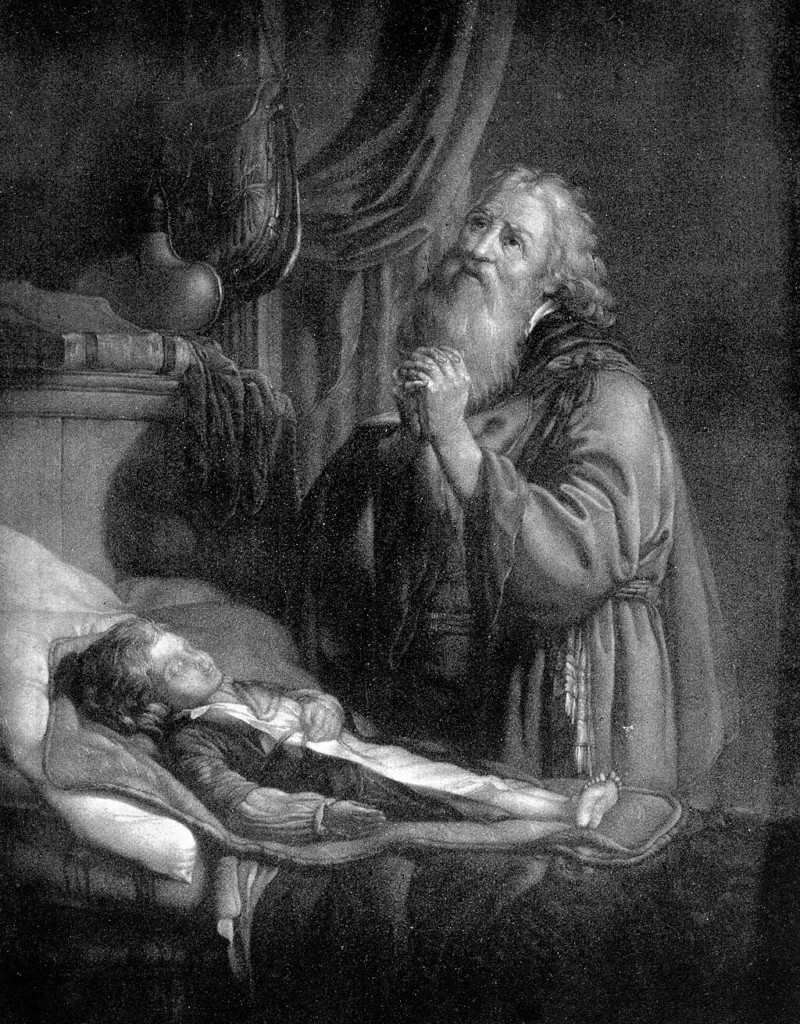

In medieval Europe, these ancient ideas merged with religion. The body was seen as a mirror of the soul, its health tied to sin, grace, and divine will. Illness might be punishment, a test of faith, or a sign of spiritual imbalance that demanded prayer as much as herbs.

Healing was never only physical. Remedies grew alongside devotion, with pilgrims crossing long distances to touch relics and sacred bones. Many believed these holy remains could shield them from illness or even turn back the course of disease.

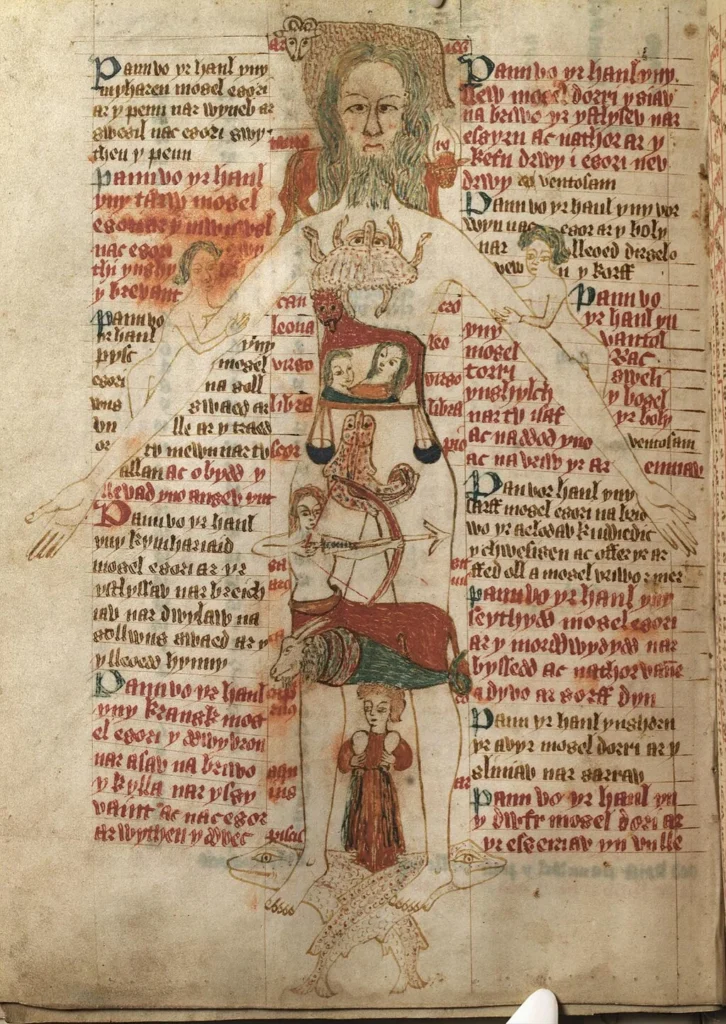

In the past, doctors often began their work with something as ordinary as a urine chart. They studied color, smell, and thickness, and in some cases even tasted the liquid to judge its qualities. At the same time, they looked at the patient’s skin, weighed the position of the stars, and then decided what cure to give.

Astrology guided much of this practice. The moon’s phase could decide when to set a broken bone, and childbirth was sometimes delayed or hastened to match what was seen as a safer alignment in the sky. To heal the body, physicians believed they also had to respect the heavens.

Ancient Cures in Indian and Chinese Traditions

Medicine in Europe followed the theories of the four humors and the teachings of the church. In India, Ayurveda shaped healing around energy and balance. In China, treatments focused on rhythm and flow. All of these systems treated the body as part of a wider natural world, shaped by air, water, fire, and earth.

Ayurveda taught that health came from balancing three forces, known as vata, pitta, and kapha. Remedies came from the kitchen and the fields: turmeric, neem, ghee, and careful breathing through yoga. Healers adjusted cures to match the season, the food a person ate, and the rhythm of their daily life.

Chinese medicine rested on the idea of qi, a life force that flowed through the body like a river across land. To keep that energy moving, healers used needles, herbs, and touch. Balance was restored with small, careful adjustments.

Organs were understood to carry more than their physical duties. The liver was tied to anger, the lungs to grief, and the heart to joy. Healing, then, meant more than treating the body. It also meant easing the emotions that weighed on it.

Witch Bottles and Burnt Feathers

In many rural communities, medicine began with tradition rather than science. Mothers passed down remedies to daughters, and neighbors shared cures that had traveled by word of mouth for centuries. In parts of Europe and North America, families buried “witch bottles” beneath their hearths, filling them with hair, nails, or even urine to keep sickness away. People burned owl feathers to chase off fevers, and some swallowed mercury, believing it could cleanse the body from within.

Every region shaped its own cures, guided by stories, local plants, and seasonal rhythms. Healing often came with small rituals or whispered words, a mixture of the practical and the mystical that became part of daily life.

In forests and mountain villages, women tended herb gardens and collected roots, bark, and charms with care. They knew when to harvest, what to boil, and how to prepare tonics under certain moons or seasons. Their knowledge was memory preserved, passed carefully from one generation to the next.

These women were midwives, healers, and caretakers of both health and spirit. Communities relied on them in times of birth, illness, and misfortune. Yet the same power that brought respect could also bring fear. When crops failed or neighbors grew suspicious, the healer might suddenly become the accused, branded a witch by the people she once served.

The Golden Age of Quackery

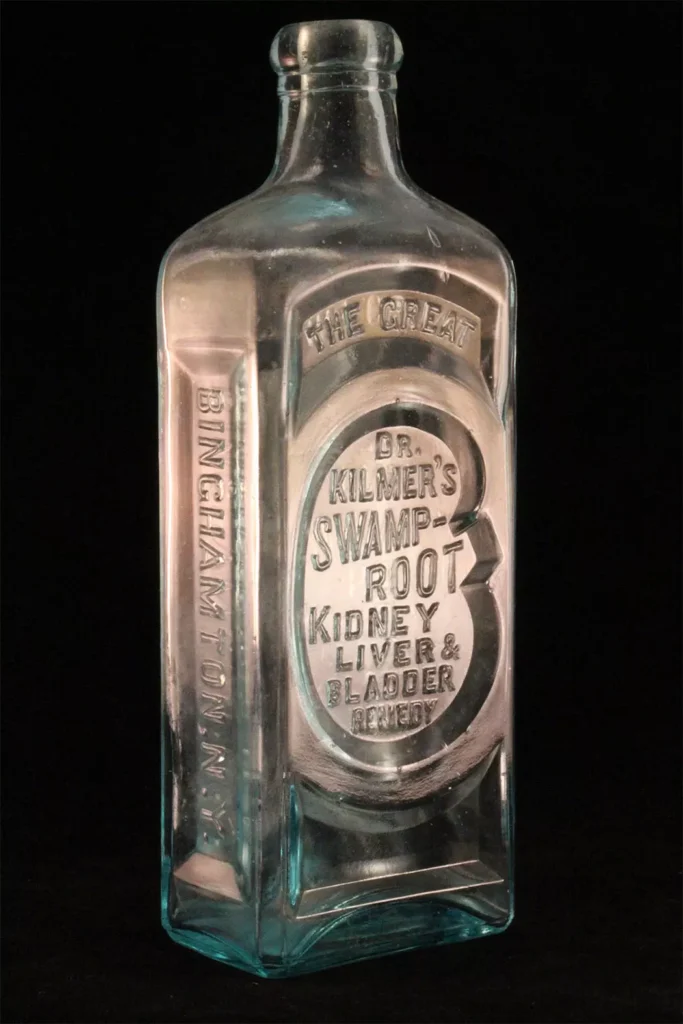

By the 1700s and 1800s, medicine entered a new age filled with spectacle and bold promises. Newspapers and broadsides advertised miracle tonics that claimed to cure baldness, heartbreak, or almost anything at all. Showmen drove into towns with painted wagons, selling bottles filled less with science than with hope.

Many of these cures targeted women. Elixirs mixed with opium or chloroform were sold as calming restoratives, promising rest and vitality. Labels spoke of purity and health, but inside the bottles were ingredients that often disturbed the body more than they healed it.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, medicine cabinets looked very different from today. One popular tonic mixed gold, strychnine, and alcohol, promising renewed strength with every glowing sip. Another encouraged calm by adding drops of radium, a substance that seemed as mysterious as it was dangerous. Mothers gave morphine syrups to soothe teething babies, comforted by the elegant labels and polished claims printed on the bottles.

Cures appeared for nearly everything. Pills claimed they could make people taller, brighten the skin, or even restore lost teeth. Advertisements filled newspapers with ornate lettering and bold promises, insisting that beauty, health, or youth could be purchased for the price of a single vial.

When Radiation Was Health

Radiation, still new and poorly understood, carried an air of wonder. Products infused with radium made their way into face creams, chocolates, and toothpaste. The most famous of all was “Radithor,” a radioactive water marketed as a tonic for athletes and businessmen chasing stamina and success.

One wealthy industrialist drank so much Radithor that his jaw began to crumble, yet his misfortune did little to slow the fascination. Radium’s invisible glow captured imaginations, and shelves filled with products that mixed scientific discovery with promises of modern vitality. Shoppers saw progress in each glowing bottle.

Even spas joined the craze. Some opened rooms filled with radon gas, assuring visitors that the air would energize the blood and quiet the mind. The tiled walls, warm lighting, and careful design gave the impression of entering a new age of healing.

People often left such places refreshed and hopeful, convinced they had found a cure supported by science. What they carried home in their bodies, however, lingered in silence, unseen and unquestioned, a reminder of the faith placed in modern promises.

Strange Tools and Stranger Theories

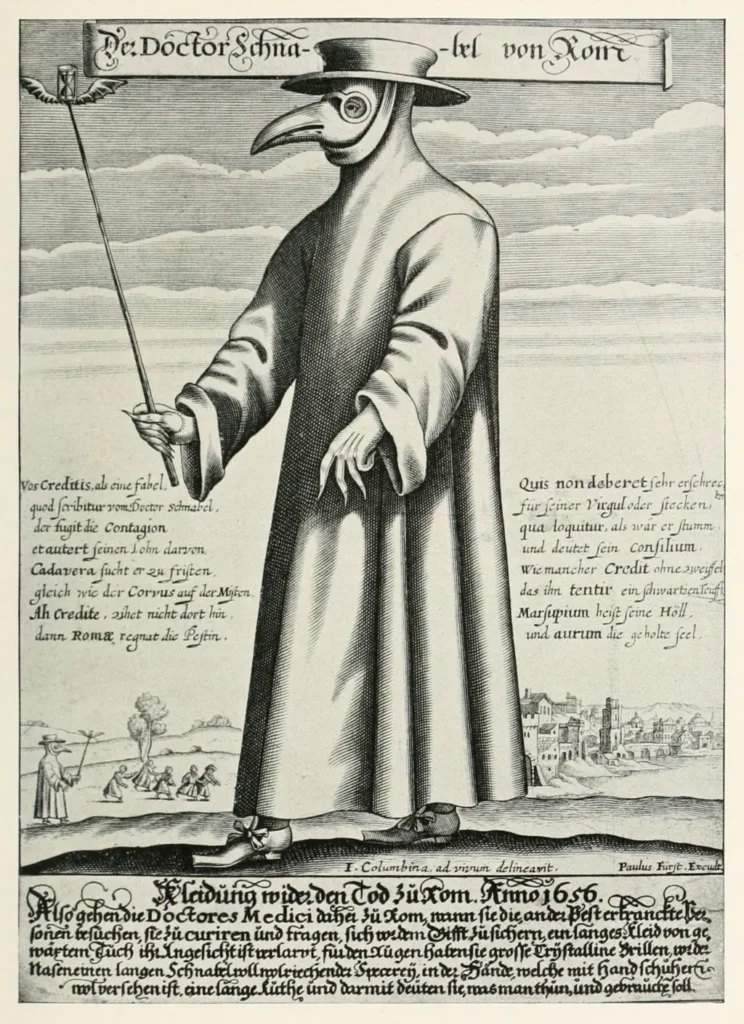

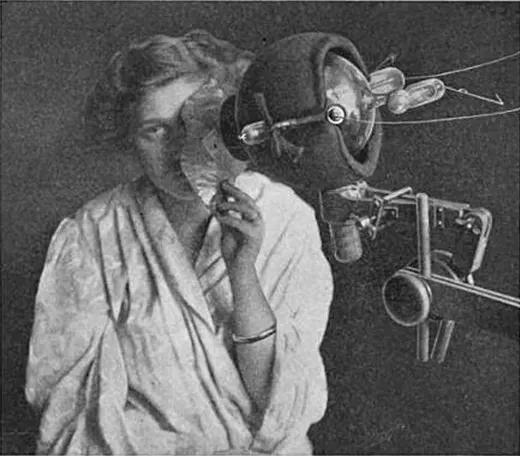

Old medicine left behind tools that looked as unsettling as they were beautiful. Trepanation drills, made to bore holes into skulls and release pressure or spirits, sat beside polished steel scalpels with ivory handles. Glass jars for cupping gleamed in the light, their fragile forms meant to draw sickness from the skin.

Some instruments even mimicked life. Artificial leeches buzzed with mechanical parts, promising to do the work of real ones. Treatments that were considered effective often appeared in strange shapes, guided less by science and more by custom, belief, and the steady confidence of the healer who used them.

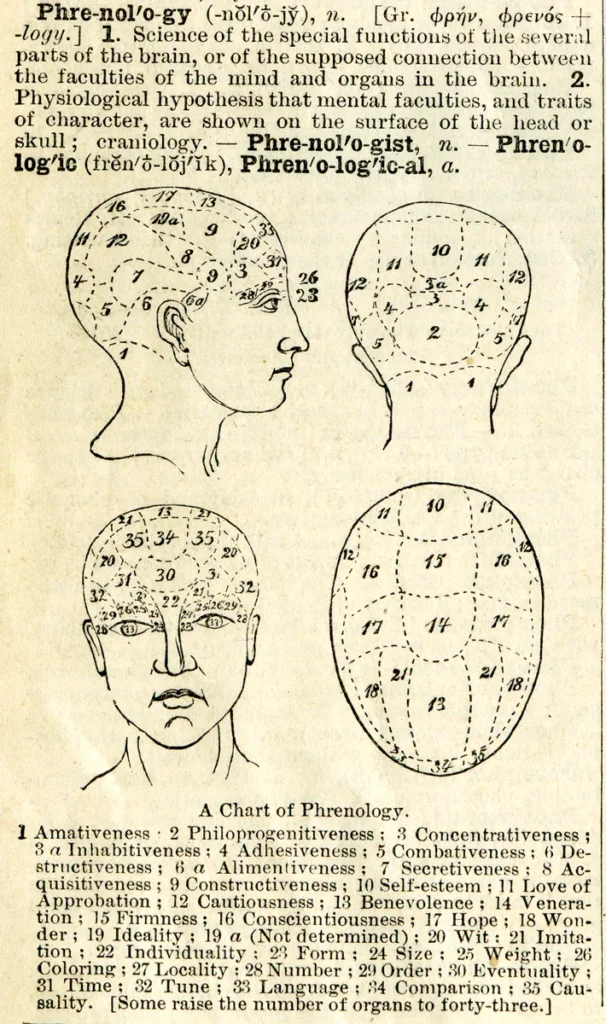

Theories were often drawn into careful diagrams. Phrenologists traced the bumps of the skull, convinced that character and habits could be read in bone. Others turned to the soles of the feet or the iris of the eye, believing that every line and curve connected to hidden systems deep inside the body.

Reflexology and iridology were part of this effort to read illness as if it were a text. To their followers, the body itself spoke a language that could be understood through touch, observation, and faith.

The Ghost of Belief Still Lingers

Many of these practices now sound like performance more than medicine. Yet belief has always been a powerful drug. Whether through powdered mummy, star charts, or glowing bottles of uranium, people looked for remedies that fit the stories they told about pain and healing.

Modern medicine may follow different rules, but the longing for wonder still lingers. People trust in crystals, sip teas that promise cleansing, and share cures science has yet to prove. The past has not vanished. It continues, wearing new clothes.