Cindy James spent almost seven years telling people that someone wanted her dead. By the spring of 1989, the story sounded so extreme that it split every room. Either a quiet nurse from Richmond had been hunted by a sadist who never slipped. Or she had built the terror herself. There was almost nothing in between.

This two part investigation draws from The Gazette’s 1989 serialization of Neal Hall’s book The Deaths of Cindy James, along with public records and the official Wikipedia account of her case. Unless otherwise indicated, direct quotations from Cindy’s letters and key witnesses are taken from that original reporting.

Cindy James was born Cynthia Elizabeth Hack in 1944 in Oliver, British Columbia, one of six children in a disciplined, close watching household headed by an air force officer and teacher. She grew into a competent pediatric nurse, quieter than some, self contained, apparently reliable. People who worked with her trusted her with difficult children and difficult parents.

In 1966 she married South African psychiatrist Roy Makepeace, eighteen years older, charming, complicated, and already a source of unease for her family. They believed he had too much influence over a woman they still saw as gentle and suggestible. The marriage slowly cooled. Cindy hinted at violence, while Makepeace insisted he had done little wrong. The distance grew.

By 1982 the marriage had broken. Cindy changed houses, kept working, and tried to build a life that felt separate. That autumn, the calls began. Breathing on the line. Obscene threats. A voice that shifted tone as if it belonged to several men, or to one man who had practiced. She reported them to the RCMP and started keeping notes.

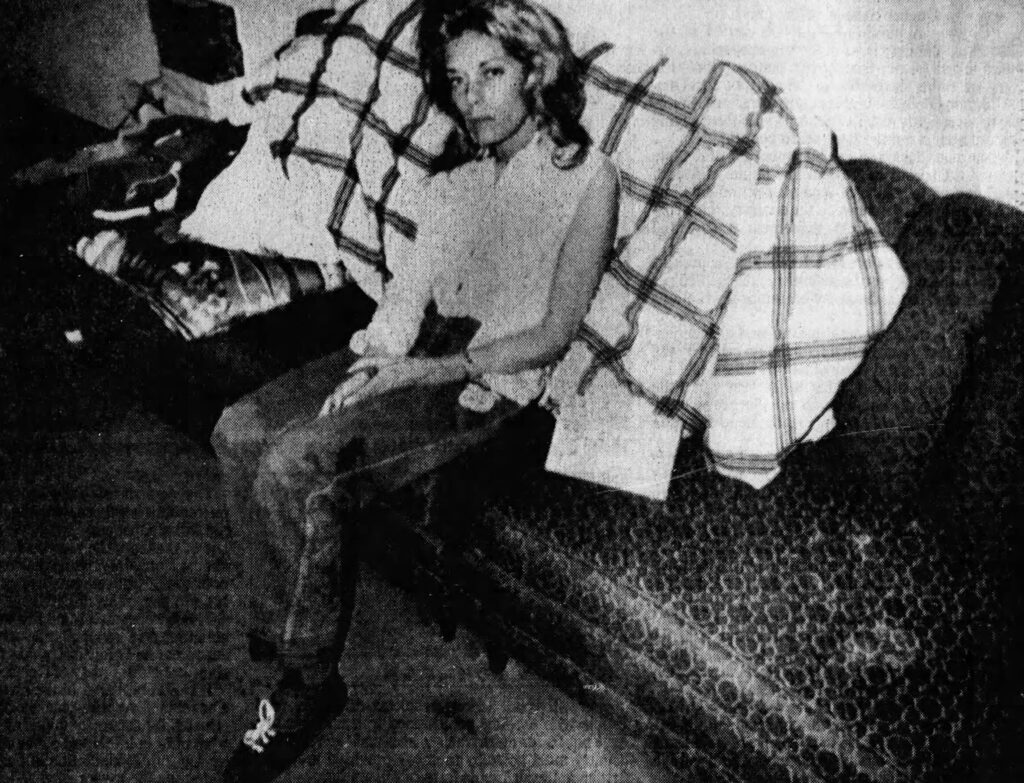

Cindy James, a Vancouver nurse who believed she was being stalked

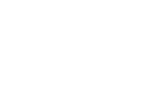

Lights were smashed. A rock came through a window. A pillow on her bed was slashed. Neighbors reported a man loitering outside. Someone left crude, cut and paste notes with violent images. Cindy confided fears about her estranged husband, then withdrew them, then circled back. The first detectives logged her complaints and went looking for someone who never seemed to stay.

Officers found phone lines cut in five places. A dead cat appeared in her garden. Another note showed a woman with her throat slashed and a greeting twisted into a threat. The pattern did not feel like a one off. It felt staged, deliberate, obsessed with humiliation. Friends saw Cindy’s world tighten. The police presence grew. So did everyone’s doubts.

Patrick McBride, an RCMP officer who briefly boarded at her house, heard some of the calls and watched the unease. He also saw Makepeace turn up outside, sitting in his car, saying he wanted to catch whoever was after her. The circle around Cindy turned more claustrophobic. Lover, ex husband, investigators, neighbors, each with their own theory. None with proof.

The first apparent physical attack came in January 1983. Cindy’s friend and coworker Agnes Woodcock arrived to visit and found the house quiet. She walked through, calling Cindy’s name. In the yard she discovered her lying on the ground with a nylon stocking knotted tight around her neck. When Cindy recovered, she said two men had dragged her into the garage and threatened to kill her sister.

Doctors noted injuries but no conclusive signs of sexual assault. Police asked Cindy to see a psychiatrist. She refused, worried that if she did, nobody would believe anything she said again. Instead she went back to work with children and tried to harden her routines. New address, new number, security measures, watchful friends. The calls and notes followed anyway.

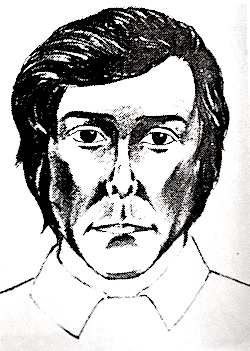

How the Cindy James stalker case confused the RCMP

She hired private investigator Ozzie Kaban. He equipped her with a silent alarm, radios, motion sensors, and advice. Cindy carried the panic device in her purse, sometimes in her hand when she walked from car to door. Even with all that equipment, the incidents kept coming. Cut phone lines. Notes with crude threats. Strangled cats. A sense that someone enjoyed rehearsing her fear.

In early 1984, Kaban rushed over after hearing strange sounds over the two way radio he had given her. He found Cindy on the living room floor, a paring knife through her hand, a message pinned with it that told her she must die. A needle mark showed on her arm. No drugs appeared in her system. Police began to talk quietly.

Some officers believed there had to be a real tormentor. The damage to her dog, Heidi, and the dead cats felt too brutal for the Cindy they thought they knew. Others started to suspect a constructed narrative, part genuine fear, part self orchestrated. Files filled with photographs, burnt paper, broken glass, yet almost no traceable fingerprints or footprints. Evidence that went nowhere.

By 1985 Cindy’s mental health had clearly frayed. She was hospitalized after an overdose, then again for depression and anorexia. Psychiatric reports sketched a bright woman with deep anxiety and volatile moods. One consultant believed she suffered from a complex personality disorder and unresolved trauma. Another thought she was under siege from something, inside or outside, he could not say. Everyone had language. Nobody had certainty.

The RCMP ran costly surveillance operations. They watched Cindy. They watched Makepeace. They watched other men who had drifted into the case. They tapped phones. They analyzed notes. They brought in a knot expert to study the nylon stockings she was so often found bound with. For years, every lead dissolved. The file grew into one of British Columbia’s most expensive.

Cindy tried to take back control where she could. She changed her name from Makepeace to James. She altered her car’s color. She moved houses. She leaned on Agnes and Tom Woodcock, who slept over often so she did not feel alone. She started a job at Richmond General Hospital in 1987 and, for stretches, managed to look almost ordinary again.

The harassment never vanished completely. Windows were cracked. Porch bulbs loosened. Anonymous notes appeared. A chilling message arrived at the hospital in April 1989 that said “SOON, CINDY.” Another taunt, “sleep well,” appeared traced on the dew of her windshield. There were reports of attempted break ins that left no easy trail, and one scent dog track that jumped the fence and died in the dark.

By May 1989 Cindy James had spent nearly seven years inside this maze. She had loyal supporters who believed every word. She had officers who had spent careers on her complaints and no longer believed at all. She had her own diaries, her own silences, her own sense that time was running out. Into that tension came one strangely hopeful week.

Five days before she went missing, Cindy wrote to her youngest sister, Melanie Cassidy, who lived in Whitehorse. The letter admitted that someone was “still getting harassed from time to time by someone trying to break in here,” but the tone turned, for once, toward light. Gord Lalonde, the husband of her friend Dorene Sutton, was going to wire a sensor along her fence.

She explained that if someone stepped into the yard, the device would alert them quietly, so they could call police “while he is busy doing his thing.” She wrote, “I’m really hopeful we might actually catch him soon. Wouldn’t that be wonderful! I could actually start living a normal life again. I’ve almost forgotten what that feels like.”

“The police have been pretty useless,” she added, “so it would be wonderful to hand him over on a silver platter.” She signed off to get ready for a visit from “Marion,” her former supervisor and friend. The letter did not sound like a goodbye note. It sounded like a woman clinging to order, hardening plans, almost daring to hope.

The Cindy James case in the weeks before she vanished

Marion Christensen had known Cindy since the days they worked with emotionally disturbed children. She admired Cindy’s patience, her soft voice, the way she kept showing up for the hardest kids. By 1989 Marion also knew the toll the threats had taken. Cindy’s world had shrunk to alarm codes, locked curtains, routines measured in inches and minutes.

On Thursday, May 25, Marion called after lunch to tell Cindy she and her husband would be away for a few days. Cindy sounded better than she had in years. She told Marion she was starting a five day break from Richmond General. She had social plans, a child’s birthday to attend, and friends coming over for bridge that night. Her voice felt bright.

Cindy also mentioned a run of attempted break ins after a long quiet spell and admitted she sensed “pressure was building up and something was going to happen.” It was the old dread, spoken almost casually. Then she brushed past it and focused on the makeover she had been meaning to get. That afternoon, she drove to The Bay at a Richmond mall.

There she sat for a cosmetic consultation, looking for something that would soften a facial skin problem and help her feel more like herself. Staff remembered her as polite and hopeful. To people who loved her, that appointment mattered. You do not book a makeover and a bridge night and a child’s present if you are walking yourself toward an exit.

A little before four, Cindy arrived at Richmond General to pick up her paycheque. Payroll clerk and neighbor Tammy Carmen told her cheques could not be handed out until four, so Cindy went for coffee with nurse and friend Diane Yong. Diane admired the makeover. Cindy told her things had been quiet for two weeks. Almost too quiet. She worried “something big” might be looming.

They agreed to meet for dinner the next evening. Cindy sounded steady and engaged. When she returned for her cheque, Tammy noticed how “bubbly” she seemed, pleased with the new look. Friends later repeated the same impression. In their eyes, Cindy James in late May 1989 looked less like a woman unraveling and more like someone trying to claim a normal life again.

That afternoon she shopped for a gift for Adrian, the eight year old son of her close friend Dorene. She phoned another close friend, Agnes Woodcock, to ask, “What do I buy for an eight year old.” She invited Agnes and her husband, Tom, to come over that night, play bridge, stay over. The plan sounded simple, safe, exactly the sort of anchor Cindy relied on.

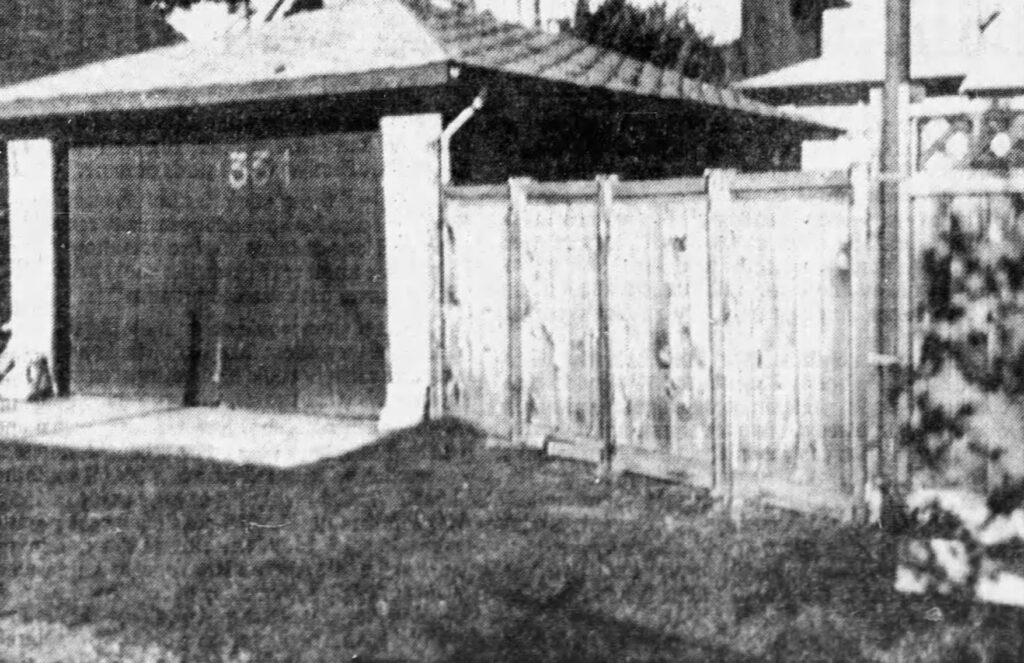

Around ten that night, the Woodcocks pulled into Cindy’s driveway on Claysmith Road. Agnes tooted the horn. Normally, Cindy would appear at the window and wave. No one came. The house was dark in the wrong way. Cindy’s blue Chevrolet Citation was gone. Agnes knocked at the front door. No answer. She and Tom walked around to the back. Still nothing.

They checked with Richard Johnston, the tenant downstairs. He told them Cindy had left around four or four thirty, saying she would deposit her cheque and do some shopping. It sounded reasonable. Yet Cindy had promised to be home by dark. With her history, breaking that promise without a call did not feel casual. It felt wrong enough that the couple sat in their car, thinking.

Agnes decided to swing past Blundell Centre, the mall where Cindy usually banked. In the lot, she saw it. “There’s her car.” They pulled close so the headlights washed over the Citation. Grocery bags sat on the front seat. A wrapped gift lay inside. The car doors were locked. From a distance, nothing looked obviously smashed. It was the placement that scraped at her.

Cindy normally parked right in front of the bank, in the light, as close to the entrance as she could manage. Tonight the car sat farther out, in a relatively empty stretch of lot. Agnes felt a jolt of instinct. She told Tom not to touch the vehicle. “Let’s just go tell police it’s here.” They turned away from the car and headed for the station.

What happened next in that station lobby, and out in that parking lot under the fluorescents, would decide whether Cindy James’s disappearance was treated as urgent or postponed, as a crisis or as more noise. It would take a patrol car, a flashlight, and a drop of blood on a door to push her story into its final, permanent chapter. That is where Part Two begins.