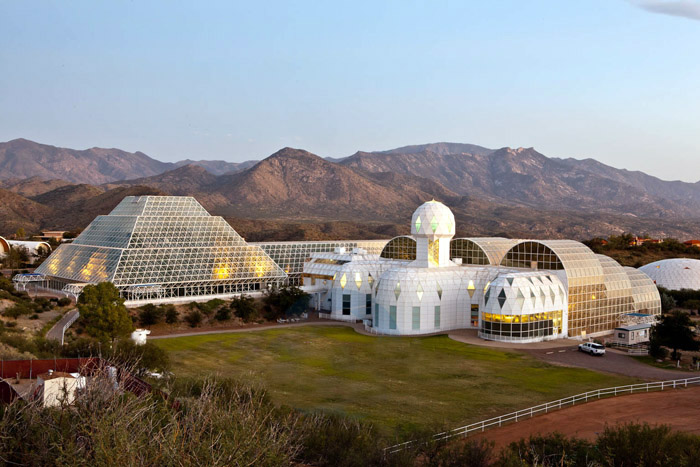

The project Biosphere 2 was meant to be a self contained Earth, where all matter, including air, water, food, and waste, would naturally recycle without aid from the external world. It was an unprecedented attempt of an unparalleled size, meant to be a test on what living on Mars, or other such inhospitable planets might demand.

The Biosphere 2 experiment in 1991 and the “mini Earth” idea

Now, more than three decades later, the same facility has become the unlikely backdrop for a global influencer’s youtube video, bringing this scientific oddity to the attention of millions of viewers.

Biosphere 2, located near Tucson, Arizona, once the site of advanced ecological research, has again captured public attention after YouTube creator MrBeast (Jimmy Donaldson) and his crew filmed a segment there. In his latest video, that focuses on cutting edge technologies and futuristic research, MrBeast walked from the facility’s iconic rooftop into its rainforest and ocean biomes, describing the site as a “mini Earth” that could hint at what could exist, in terms of life, in Mars and other planets.

A 3.14 acre glass and steel structure constructed between 1987 and 1991, Biosphere 2 was the brainchild of John P. Allen, a systems ecologist, and was funded to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars by Texas oil tycoon Ed Bass, who envisioned a self sufficient “mini Earth.” The project was conceived as a prototype for a self-sustaining human colony in hostile environments, including places beyond Earth such as Mars, where closed ecological systems would be essential for long term survival.

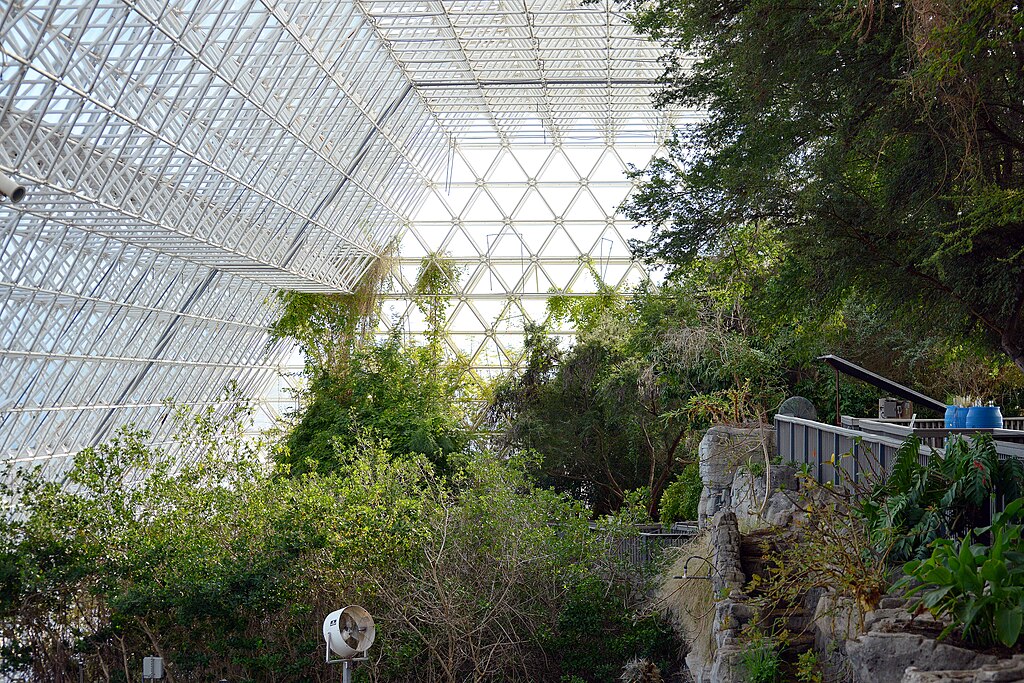

Scientists and engineers hoped that by sealing volunteers inside a carefully constructed set of ecosystems, or biomes, as they called it, including a tropical rainforest, desert, savanna, mangrove wetlands and an artificial ocean, they could observe how life behaves within a fully isolated habitat. The experiment was intended to mirror the conditions that future explorers might have to encounter on Mars, where survival would depend on the habitability of closed systems, without access to supplies from Earth.

When the facility was sealed on September 26th, 1991, eight volunteers, or “biospherians” including Abigail Alling, Linda Leigh, Taber MacCallum, Mark Nelson, Jane Poynter, Sally Silverstone, Mark Van Thillo, and Dr. Roy Walford, assumed responsibility for an entire artificial world, prepared to grow their own food, recycle air and water, and maintain every aspect of their environment for two uninterrupted years.

Many U.S. astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts, including Yuri Gagarin, Neil Armstrong, Valentina Tereshkova, and Buzz Aldrin had previously spent extended periods in outer space during the Cold War and its aftermath. Yet even the longest of these missions relied entirely upon supplies carried from Earth. Food, water, and breathable air accompanied every flight, sharply limiting the duration for which humans could remain away from their home planet.

Biosphere 2 was developed to challenge this constraint. Its purpose was not simply to keep humans alive in total isolation, but to demonstrate that a closed ecological system could, in theory, support human life indefinitely, without ongoing access to Earth’s resources.

The mission quickly drew intense public scrutiny when, early on, a crew member suffered a serious finger injury and was temporarily removed for emergency surgery. Her return with supplies, including a duffel bag, fuelled press speculation over how “self sufficient” the experiment truly was. Critics questioned whether the system was ever fully closed, and whether such medical intervention would be possible on a distant planet.

Despite the outward theatricals though, several biospherians later reflected that the project’s unpredictable twists were, in fact, part of experiment itself. “Just the fact that the same number of people came out as went in is a triumph,” said Mark Nelson, one of the original eight. “We built it not because we had the answers. We built it to find out what we didn’t know.”

Insistence upon the seriousness of the experiment however, did little to temper the intense media attention the project attracted. The scale, secrecy and ambition around which it was constructed, made it irresistible to journalists, many of whom framed it more as a high stakes social experiment, than an ecological experiment.

Despite the speculations and controversies surrounding it, the project headed to a relatively stable start, with a high crew morale. Problems however, soon began to emerge, with food being the primary among them.

Crop yields fell far below expectations, while the labour required to maintain the agricultural systems proved to be a lot greater than anticipated. “We really could have used more calories,” recalled Linda Leigh. Many crops grew too slowly or demanded excessive effort, and even small comforts were scarce. The wild coffee bushes inside, for instance, required nearly two weeks to yield enough beans for a single cup.

“It was hard to make exciting food,” Leigh noted. To maintain morale, cooking duties were rotated among the crew. Some improvised creatively “someone once made a taco shaped like a dinosaur”, while others produced meals remembered less fondly, such as cold potato leaf soup. Over time, every member of the crew experienced significant weight loss, and grew increasingly irritable.

Why oxygen fell in Biosphere 2 and how the crew split

Compounding the food crisis was a more serious problem. Oxygen levels fell faster than anticipated, and carbon dioxide levels rose exponentially. While Earth’s atmosphere contains about 21 per cent oxygen, levels inside Biosphere 2 dropped to roughly 14.2 per cent, comparable to high altitude. “It felt like mountain-climbing,” said Mark Nelson, further recalling that some crew developed sleep apnoea and struggled to speak without pausing for breath. Work slowed to a sluggish pace, and any further decline, he noted, could have posed serious health risks.

The physical stress took an inevitable social toll. Nelson would later describe the experience as “a marathon group therapy session.” Tensions surfaced gradually, and cups were thrown, and there were incidents of spitting, though no physical violence occurred. “It was more a coldness,” Leigh explained. “Not wanting to be around each other.” The crew ultimately split into two groups of four, divided over how to respond to the crisis. One faction favoured bringing in supplemental food and oxygen to ensure that declining health did not compromise the scientific work. The other opposed intervention, believing that altering the conditions would undermine the experiment’s purpose.

While media coverage at the time portrayed this rift as evidence of personal failure or mismanagement, researchers later emphasised that such divisions are common in small groups subjected to long term confinement, limited privacy and sustained physical stress.

Studies of Antarctic research stations, submarine crews and spaceflight simulations have repeatedly shown that prolonged isolation can intensify minor disagreements, leading to factionalisation even among highly trained and motivated individuals. In Biosphere 2, the relentless workloads and absence of any possibility of withdrawal exacerbated this strain. The sealed environment allowed no social escape, turning ordinary kerfuffles into prolonged divisions.

Crew members later recalled being woken by television cameras pressed against the glass, as daily reports on their health, relationships and diet began to eclipse the experiment’s scientific aims. Tourists and schoolchildren arrived in droves, photographing the visibly emaciated crew. Leigh remembered a visit from renowned anthropologist Jane Goodall with wistful irony “She observed us like we were captive primates,” she said. Critics seized on the spectacle as evidence of scientific hubris, while supporters argued it was a misunderstood experiment undone by unrealistic public expectations.

Parallelly in the outside world, the conditions inside had begun to provoke widespread debate regarding the experiment’s ethical implications. Reports of declining health, food shortages and falling oxygen levels raised questions outside the facility about whether the project had crossed the boundary between scientific research and human risk. Although John Allen and the management team initially sought to downplay the severity of the problems, the strain inside the enclosure soon became increasingly difficult to conceal.

Eventually, additional food was introduced into the system, followed by two controlled injections of oxygen. For the biospherians, the change was immediate and profound. “People started laughing like crazy and running around,” recalled Mark Nelson. “I felt like I’d been 90 years old and now I was a teenager again. I realised I hadn’t seen anybody running for months.”

Outside the glass walls, however, the reaction was far less celebratory. As media debate intensified, critics increasingly dismissed the project as lacking scientific rigour. What had been conceived as a pioneering ecological experiment was recast by some commentators as an elaborate act, rather than research or, as one critic memorably described it, “trendy ecological entertainment.”

By then, the public narrative had already formed. Inside, the experiment continued in a diminished, and somewhat altered form. Though the biospherians returned to work with renewed vigour, questions of credibility lingered. Biosphere 2 had become an improvised system, functioning on compromise, far from the pristine enclosure its creators had envisioned

The first closure of Biosphere 2 formally ended on September 26, 1993, exactly two years after the crew had entered the sealed environment. All eight biospherians emerged alive, markedly thinner, physically exhausted, and deeply impacted by the entire experience. The project had achieved its most basic objective of sustained human survival inside a closed ecological system for an unprecedented duration.

A second, shorter mission began in March 1994, but it would not last. Internal disagreements over management, mounting financial pressures, and continued criticism of the project’s scientific governance led to its premature termination after just six months. By the mid 1990s, control of the facility had shifted away from its original leadership, and the vision of repeated, long term human closures, was visibly diminished.

Biosphere 2 today at the University of Arizona and the Mr Beast bump

Contemporary visions of Mars colonisation are far disconnected from the optimistic projections of the 1990s. Perhaps humbled by lessons learnt from experiments such as Biosphere 2. Engineers and ecologists today acknowledge that survival in isolation is not merely a matter of technology, but of ecology, psychology and governance. Closed systems today must be designed to account for cascading biological feedback, human conflict, nutritional limits and ethical oversight precisely the pressures that surmounted inside the glass walls of Biosphere 2.

The experiment itself, however, was perhaps too futuristic for the age in which it was conducted. Where Biosphere 2 was once judged prematurely under the constant glare of media scrutiny, it is now widely considered to be a commendable effort, and serves as a reminder that replicating Earth is far more difficult than one might imagine.

This softened view has found an unlikely catalyst in popular culture. Standing atop Biosphere 2, wearing the same spacesuit used by George Clooney in the film Gravity, YouTube creator MrBeast recently invited his audience inside what he described as “one of the world’s most unique research facilities.” “Let’s go be Martians for a day, boys!” he declared, before descending into the glass enclosed world below.

Beneath the structure today lie more than 300 species distributed across five stabilised ecosystems, consisting of an ocean, mangrove wetlands, tropical rainforest, savanna grasslands and fog desert biomes. Unlike the 1990s experiment, these systems today operate under the stewardship of the University of Arizona, which has repositioned Biosphere 2 as an open, working laboratory rather than a sealed ‘biosphere’. “In addition to our research, people can visit every day,” said John Adams, the facility’s deputy director and chief operations officer. “That gives us the opportunity to share both the historical significance of Biosphere 2 and the kind of science that can only happen here.”

Inside the rainforest biome, researchers are currently exposing plants to temperatures as high as 140 degrees Fahrenheit to study how extreme heat affects photosynthesis and leaf function. Nearby, in the ocean biome, scientists are preparing large scale coral “arks” designed to accelerate reef restoration worldwide. The desert biome, meanwhile, has recently welcomed a new population of Sonoyta pupfish, adding to its tightly managed biodiversity.

Student researchers working inside Biosphere 2 during the filming, described the striking scale of coordination behind it. One of them noted that while there was no direct interaction with MrBeast’s crew, the production itself was intriguing. “We didn’t actually interact with the crew, but it was really cool to see all of the behind the scenes work,” she said. “I couldn’t believe the scale of the production. There were so many cameras and people involved. It was incredible how much work goes into a single YouTube video.”

She further added that the attention brought by MrBeast offered something earlier decades of research could not. “I’m grateful that he came here and experienced Biosphere 2 for himself, and showed it to a wider audience. I really encourage people to see it for themselves. It’s such a remarkable place.”