I first watched National Treasure as a child and imagined what it would be like to chase secrets across maps and monuments. The story of Benjamin Franklin Gates, who pursued hidden treasure while outwitting villains, seemed like pure invention. Yet in Virginia, a mystery suggests such adventure might not belong only to film.

It is part of a long tradition of stories about fortunes hidden beneath the American landscape, some of which I explored in 24 Lost Treasures Across America That Were Found or Still Missing.

The Beale Ciphers centers on Bedford County, where a hoard of gold, silver, and jewels is believed to lie beneath the soil. The treasure is said to be protected not by locks or guards but by three encrypted messages. Copies of these ciphers have circulated for generations, drawing fortune seekers nationwide.

The mystery begins in April 1817, when Thomas J. Beale left Virginia with thirty men who called themselves gentleman adventurers. Their expedition started as a buffalo hunt across the Great Plains, then part of the Spanish province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, today northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

They hunted during the day and camped by night in valleys and ravines. One evening, a glimmer of gold was found in a rocky cleft, and their expedition changed. For the next eighteen months, they mined the site, extracting gold and silver, and by the end, they had accumulated a fortune of staggering weight.

Beale was entrusted with the responsibility of moving the hoard eastward. The task proved as demanding as the mining itself. During the journey, he stopped in St. Louis, exchanging part of the bullion for jewels, lighting the load while preserving value. On his return to Virginia, he selected Bedford County as the site to hide the treasure.

He dug a stone-lined vault six feet into the ground and concealed the hoard. He created three encrypted messages to safeguard the fortune and its inheritance. One described the contents of the vault, another identified the heirs, and the last revealed the precise location. Together, they became known as the Beale Ciphers.

Accounts describe Beale as a striking, tall, dark-haired man with eyes to match and a complexion marked by years outdoors. He often stayed at Robert Morris’s Washington Hotel in Lynchburg, Virginia, during the winters of 1820 and 1822. In the spring of 1822, he entrusted Morriss with a locked iron box before leaving on his final journey.

Beale explained only that the box contained papers of value. He instructed Morriss to keep it secure and, if neither he nor his companions returned within ten years, to open it. In a letter from St. Louis, Beale promised that a key to decoding the papers would follow, though it never arrived.

Morriss kept the box safe far longer than the agreed decade. He waited twenty-three years, well beyond the point when he believed Beale had died, before finally opening it. Inside were several letters written in plain text by Beale alongside three pages of numbers. These were the ciphers that would capture public imagination for centuries.

Morriss struggled to solve them for the next twenty years, but his efforts brought only frustration. In 1862, at eighty-four, he passed the box and its contents to an unnamed friend. This man managed to decipher the second of the three texts, which revealed the contents of the treasure. The other two resisted all attempts.

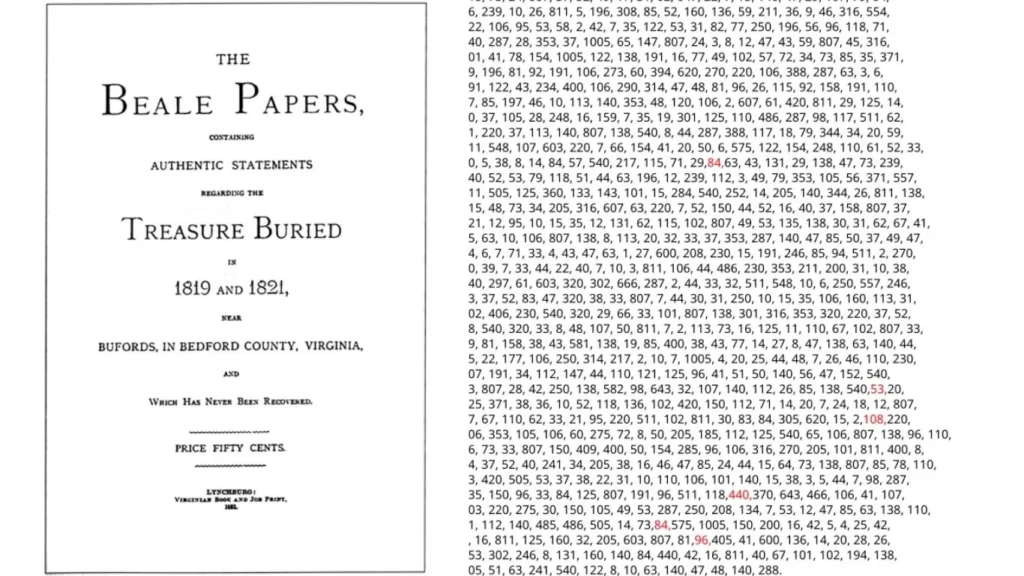

In 1885, the friend decided to share the story with the public. It was published in a twenty-three-page pamphlet titled The Beale Papers. It contains authentic statements regarding the treasure buried in 1819 and 1821, near Bufords, in Bedford County, Virginia, which has never been recovered. The pamphlet was issued by James B. Ward of Lynchburg.

Ward explained in the introduction that he published the account for financial reasons and to hand the challenge to the broader public. He hoped the immense prize might eventually fall to “some poor, but honest man.” The pamphlet sold for fifty cents and became the foundation of the Beale treasure legend.

What are the Beale ciphers?

The Beale story is remembered less for the journey and more for the remaining puzzle. Inside the iron box sat three pages of numbers that promised a fortune to anyone who could read them. The design was spare, yet it resisted casual decoding without the one thing that mattered, a key.

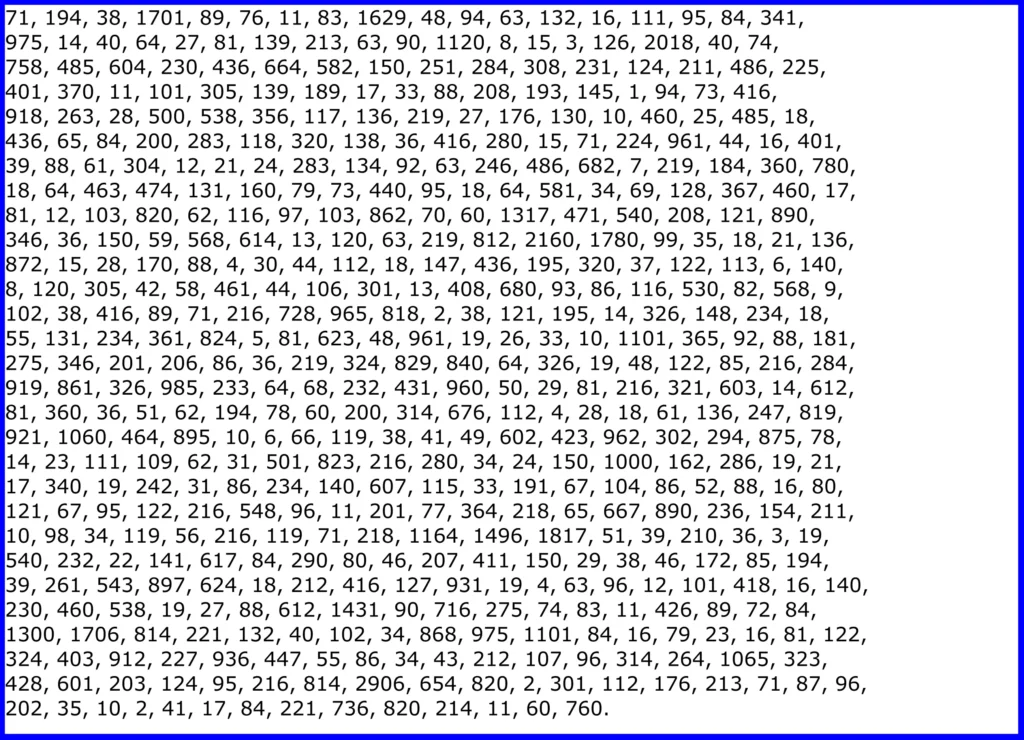

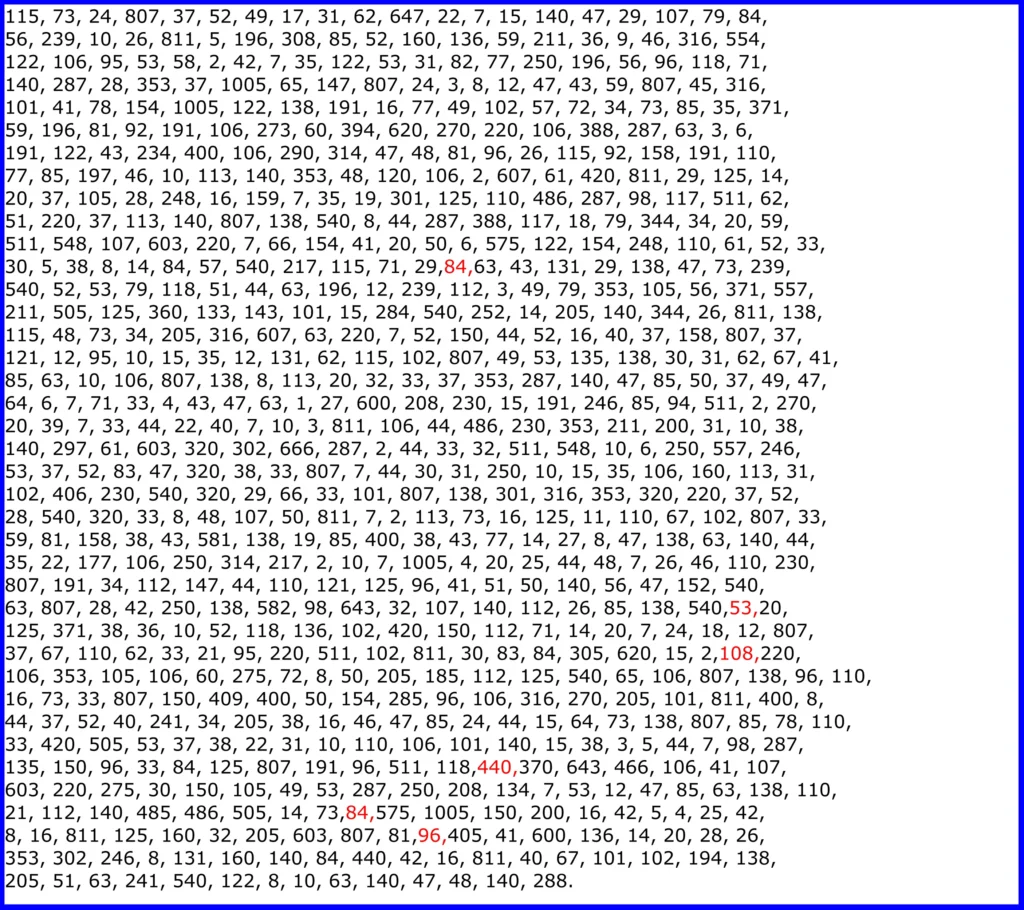

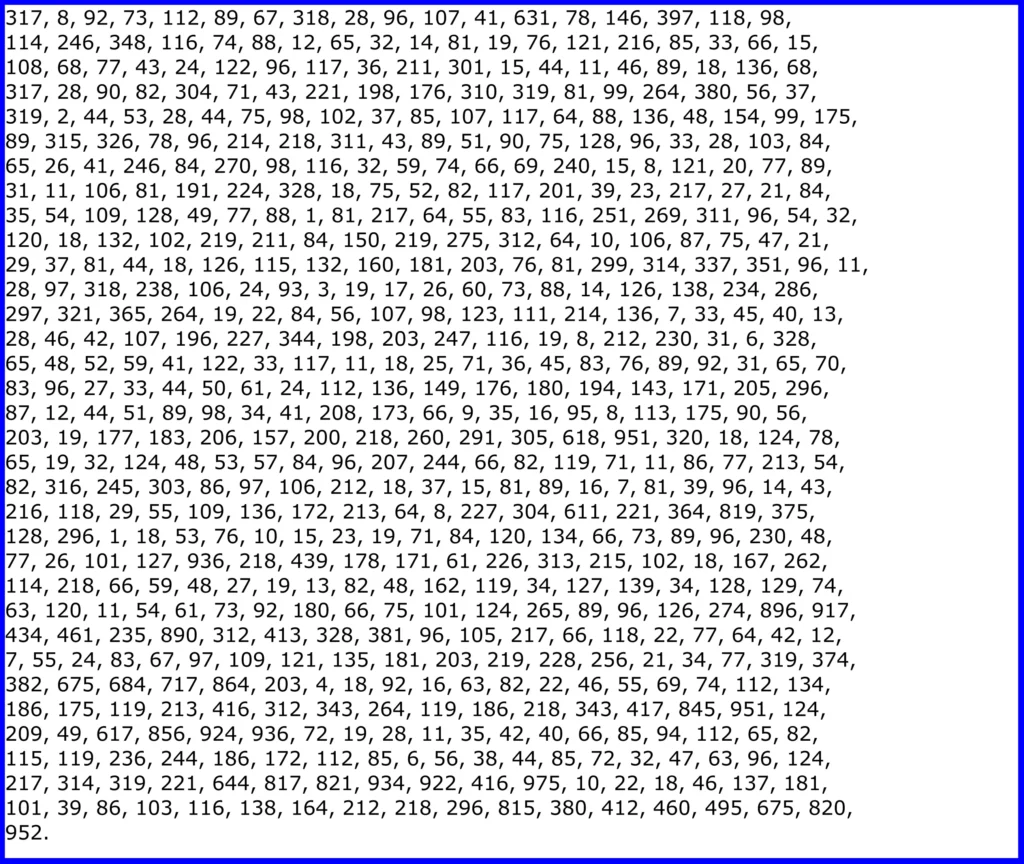

The papers are often described as three separate ciphers with specific purposes. The first contains five hundred twenty numbers and is believed to represent the exact location of the vault. The second holds seven hundred sixty-two numbers and explains the contents. The third lists six hundred eighteen numbers and names the heirs.

Each page consisted of long rows of numerals. To most readers, they seemed random, yet they were arranged with care. The system allowed one letter to be represented by more than one number, which blunted simple letter counts and kept the surface of the code from giving itself away.

The only real progress came on the second paper. An unnamed friend of Robert Morriss reasoned that the numbers might point to words in a well-known text from the founding era. He tried the Declaration of Independence and found that its words lined up with the sequence in a workable way.

The method is easier to understand than it is to execute. Match each number to the position of a word in the chosen document, then take the first letter of that word to build a message. Do this carefully, page after page, and a paragraph of plain English emerges.

The resulting passage reads like an inventory and a set of instructions. It places the vault in Bedford County near Bufords, six feet underground in a stone-lined pit. It describes iron pots with iron lids. It says the vessels rest on stone and are covered with more stone to hide them.

The text also gives quantities that demand attention. The first deposit in November 1819 reports 1,014 pounds of gold and 3,812 pounds of silver. The second deposit in December 1821 added 1,907 pounds of gold, 1,288 silver, and jewels valued at thirteen thousand dollars.

The decoding worked only because the document used as a key did not precisely match the official text. Words were counted differently. A few were added and a few removed. Some were split into two. The pamphlet that told the story recorded these adjustments, and they became part of every later attempt.

There were peculiar counting choices as well. Self-evident was treated as two words. Unalienable appears as inalienable in the Declaration, but was handled in a way that produced a usable letter. The meantime was counted as two words. Several letters were treated as standing for others in specific numbered positions.

The pamphlet even acknowledged minor errors in the transcription of the decoding. It recorded stray letters and obvious misprints such as consistcd instead of consisted and varlt instead of vault, along with other slips. None of these changed the thrust of the message, but they reminded readers that the process was fragile.

Another wrinkle came from the lack of reliable images of the original papers. Long column numbers invite mistakes in setting type and copying by hand. Over time, different printings introduced omissions and substitutions, including whether ten hundred or one thousand appears and how dates are written. Such variations created confusion about minor details.

Even with those problems, the figures invite calculation. The combined weight approaches three tons. Later estimates turned the inventory into modern units, about thirty-five thousand troy ounces of gold and more than sixty-one thousand troy ounces of silver. Those totals have been valued at tens of millions in recent years.

Are the Beale ciphers real, and has anyone solved them?

Debate over authenticity has followed the ciphers for more than a century. One early researcher, Carl Hammer of Sperry UNIVAC, used large computers of the late 1960s to study the numbers. He concluded the two unsolved pages did not behave like random strings. He probably concealed meaningful text that required a missing key.

Skeptics point to the pamphlet itself. The narrative rests on hearsay and circumstantial detail; only the second paper has ever been solved. The price of fifty cents was steep, and the publisher expected wide sales. To some readers, that combination looks like a plan to spark interest rather than an account of fact.

Long alphabetical runs appear if the modified Declaration of Independence is used as a key for the first cipher. Specialists argue that the odds of such sequences appearing several times by chance are vanishingly small. That finding has fueled claims that the first text was manipulated to produce a plausible clue rather than a genuine message.

There are practical objections as well. Critics ask why Beale would divide one essential message into three separate pages when the goal was to ensure heirs received their shares. Others note that the third paper seems too short to list thirty men and their next of kin clearly and helpfully.

Style studies add another layer. Analysts have found strong similarities between the prose in the pamphlet and the letters attributed to Beale, which hints at a single author behind both. Timelines raise questions, too. Records suggest Robert Morriss did not run the Washington Hotel until at least 1823, later than the pamphlet implies.

Number behavior has been tested in different counting systems. In base ten, the unsolved pages show uneven patterns in their final digits, which humans often produce when inventing numbers. Shift to number systems that do not share factors with ten, and the patterns flatten. The decoded page stays complex. The others look more uniform.

Copying adds confusion. Clear images of the original pages have been rare, and long columns of digits invite mistakes. Over time, printings and retellings introduced omissions and substitutions. Some versions write ten hundred, where others write one thousand. Dates vary between words and numerals. Small changes make later analysis harder than it appears.

Where is the Beale treasure now?

Uncertainty has not discouraged seekers. Expeditions have dug across Bedford County, and arrests for trespass have followed. A series of digs on the top of Porter’s Mountain produced Civil War artifacts rather than bullion. The sale of those items covered costs. The vault, if it exists, remained out of reach.

Decoders have tried every famous document they can think of. The Constitution, the Magna Carta, books of the Bible, and early Virginia charters have all served as keys. None has worked. Some argue Beale could have written his own key text and kept it private, making the remaining pages impossible to solve.

The theory that Edgar Allan Poe wrote the pamphlet has also circulated. Poe loved ciphers and wrote a story that used one. He lived in Virginia during part of the period the pamphlet describes. The dates do not match. He died in eighteen forty nine, and the pamphlet appeared in eighteen eighty five. Style studies also point away from him.

The mystery appeared in the UK’s Mysteries series and Unsolved Mysteries. The History Channel revisited it in 2011 in Brad Meltzer’s Decoded, which tied the story to the Declaration of Independence.

Writers have continued the discussion. The Beale Cipher Association published a newsletter from 1979 to 1996. Simon Singh devoted a chapter to the case in his 1999 book The Code Book. Both kept the story alive among researchers and readers.

Film and television also carried the legend forward. The award-winning animated short The Thomas Beale Cipher was released in 2010. A 2015 episode of Expedition Unknown followed host Josh Gates to Bedford County in search of the treasure.

Most recently, in 2024, Popular Mechanics journalist Dave Howard profiled modern researchers who have tried and failed to solve the two unsolved ciphers. His reporting underscored the durability of the mystery and the persistence of those still chasing it.