In September 1983, a rumour spread that tons of game cartridges had been crushed and buried in a landfill in Alamogordo, New Mexico. The story implied that the cargo buried in the landfill consisted of unsold and unwanted E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial game cartridges.

This birthed one of the most persistent urban legends in the gaming space. The E.T. game was such a disaster that it triggered the video game industry crash of 1983 and resulted in tens of millions of dollars in losses.

For decades, though, the story lived between fact and myth until, in 2014, a documentary crew unearthed more than 1,300 cartridges.

Atari was gaming’s king in the early 1980s until the bubble burst

To understand why Atari had to go to the lengths of burying the evidence of their failure, one has to appreciate their position at the time. By the early 1980s, Atari was the unofficial king of the video gaming industry.

Warner Communications had acquired them for $28 million in 1976, and Atari’s net worth ballooned to $2 billion within a few years. In fact, their sales accounted for more than half of their parent company’s revenues, and they dominated 80 per cent of the gaming market at the time.

One of their main products, the Atari 2600 console, was a rising fixture in American homes. They also produced massive hits like Space Invaders and Asteroids. Atari’s Achilles heel, though, lay in its culture of excess.

According to programmer Howard Scott, their organisational culture had a ‘fall of Rome’ feel, with a belief in unending growth.

This is what set the stage for their downfall. Atari adopted high-risk business practices, such as requiring distributors to place orders for entire years at a time. They also produced games based on projections rather than market demand and leanings.

One of the preludes to the E.T. Fiasco was the Pac-Man event. Based on the arcade game’s previous success, Atari produced 12 million cartridges, even though it had sold only 10 million consoles globally.

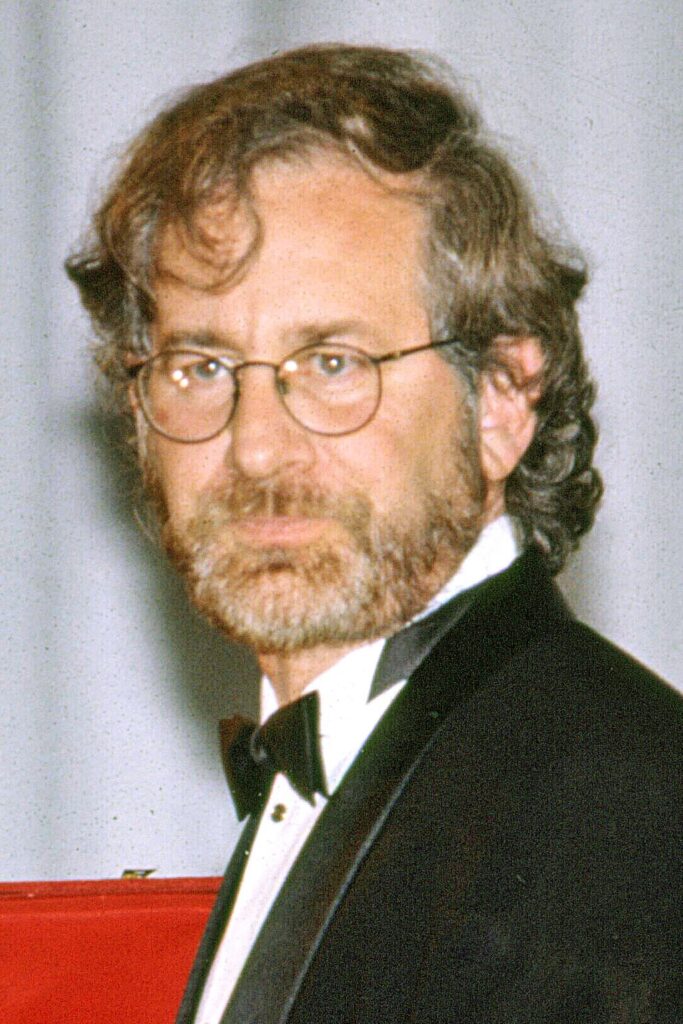

At the end of the year, they were left with 5 million unsold cartridges, excluding returns. Warner Communications secured the rights to the game following Steven Spielberg’s 1982 hit.

Atari tried to capitalise on the holiday season and asked Warshaw to develop the game within just five weeks. Having to work at home to finish the timeline, Warshaw delivered on schedule. Spielberg gave his approval, and Atari bet everything, pushing 5 million cartridges into the market.

Instead of a success, the game was a disaster as players found it frustrating to navigate. A lot of it was due to the pits that frequently trapped the E.T. protagonist during gameplay, with little guidance for escape.

Soon, it earned a reputation as one of the worst games ever made. Only 1.5 million copies were sold, resulting in $100 million in losses on that title alone and a destroyed reputation among the gaming consumer base. The market was also flooded with unsold E.T. and Pac-Man games, leading to the huge recession.

Atari buried the unsold games in 1983

As Atari’s financial situation worsened in 1983, the company realised it needed to dispose of its large excess inventory. Between 10 and 12 semi-trailers loaded with Atari products were crushed and buried at the Alamogordo landfill. Some of the local newsprint outlets also reported cases of children robbing the E.T. ‘grave site’.

To deter scavengers, concrete was poured over the area where the games were buried. That said, many embellishments were added to the act over the years leading up to the excavation. Local lore indicated millions of E.T. cartridges were buried.

An investigation showed the total number of games buried was 728,000. It was also suggested that the site was exclusively for E.T. games. Upon analysis, the recovered items were diverse, including 50 titles such as Defender, Centipede, and Missile Command, as well as E.T.

Now, while Atari’s blunders and the uncovered E.T. games became the scapegoats of the video game crash, it was a symptom of a perfect storm. Factors like poor-quality third-party games, market saturation, and the rise of personal computers compounded Atari’s disastrous business practices.

Atari also buried the games to clear inventory. Warehouse managers were simply ordered to dispose of the existing stock following the market collapse. They chose the Alamogordo landfill because it apparently had strict anti-scavenging laws.

The 2014 Alamogordo excavation turned the Atari landfill story into proof

For almost 30 years, the burial of the games was somewhere in between corporate rumour and actual history. It was hinted at in many gaming magazines and online forums, often receiving criticism for being too conspiracy-esque to be true.

This ended in early 2014, when the Alamogordo landfill became an archaeological dig site that was live-streamed to ensure believability. This endeavour was sponsored by Fuel Entertainment, in collaboration with Xbox Entertainment Studios, to produce the documentary Atari: Game Over.

This was a quest to get to the bottom of a gaming campfire tale. The experience was an interesting mix of pop-culture gimmicks and by-the-book archaeology. The landfill was designated a potential historical site and granted a permit for excavation.

The ‘punk archaeologists’ treated the site not just as a dump site, but as a place in time where 20th-century consumer culture could be uncovered. Their academic analysis contrasted with the carnival-themed setting that quickly became the norm.

Curiosity seekers, gamers, and members of the media soon gathered behind the set fences to bear witness. Someone parked a DeLorean nearby to make it more on-brand.

Joe Lewandoski, a local contractor, was key to the exercise, as he had personally witnessed Atari bury the games.

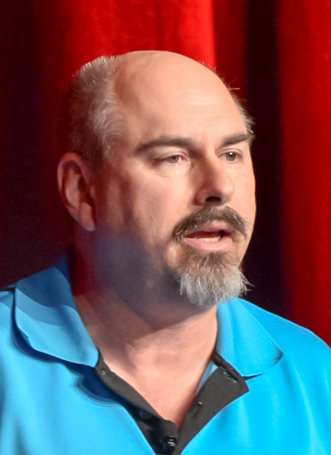

Relying on the old plans and his memory of the incident, he guided the team to the specific quadrant they should dig. There was significant tension as the heavy machinery ate through the debris. Howard Warshaw, the game’s creator, was watching at the edge of the pit.

On 26 April 2014, the backhoe picked up earth that was tangled with shards of plastic. These were Atari cartridges. These artefacts were carefully extracted from the pit and cleaned. The crowd cheered not just because the objects were found but because of the vindication of the legend. For Warshaw, it brought closure.

He had borne the weight of the game for 31 years and felt like the poster child for Atari’s failure. He stated that what struck him was that something he had done so long ago was still creating joy for people.

The physical proof of the gaming cartridges did something that criticism could not. The game had returned as a relic of history, rather than the ghost of failure.

The excavation, however, was also about discovery. Former Atari manager, James Heller confirmed 728,000 games were buried at the site. Many of these were from previously succesful titles. This revealed that the burial was not just a tomb for E.T. alone.

It was a cross-section of Atari’s despair. It was evidence that the burial was a drastic inventory clearance.

Each recovered artefact has since been catalogued and preserved in various museums. By unearthing the legend, the excavators provided the industry with an origin story for the collapse of its first golden age.

How companies handle excess inventory now, and why Atari’s case was different

What Atari did was extreme, but the problems surrounding excess inventory are widespread. Today, modern companies may use write-downs or write-offs. This is where the company decides to reduce the value of the unsold inventory still on the books. It helps to absorb the financial cost of removing it from the warehouses.

For ethical and environmental reasons, some companies may choose to donate unsold items. This works for tax benefits and to increase goodwill toward the brand. Some apparel companies are notorious for donating the previous season’s items if they cannot sell them at their stated prices.

In tech, old models or chips become irrelevant as technology advances. Sometimes the components are also harvested or refurbished in newer models, so it’s not a total waste.

That said, there are key differences in the Atari case compared to more recent contexts.

For one, the modern instances of excess inventory disposal are not as sensational. Rather than a single event, it is an ongoing and managed process.

What the Atari E.T. landfill dig changed for Warshaw and gaming history

The dig provided much-needed closure for the 30-year-old mystery. Though it continues to reflect as a cautionary tale. The E.T. game cartridges are currently housed at the Henry Ford Museum and the Smithsonian, serving as beacons of the fall of the first gaming era.

Cartridges were auctioned off by the City of Alamogordo for over $100,000, which is ironic given that the games were buried as trash.

Howard Warshaw’s story also deserves to be recognised. Following the 1983 crash, he lost his job and fortune. His trajectory went from high-flying developer to an outcast in the gaming world. Finally, he found his way back into the field of psychotherapy in Silicon Valley.

He currently helps tech workers handle the pressures he previously worked under. Warshaw found redemption after decades of ridicule in a field that does not easily forgive big mistakes.

The dig showed that the recent past, particularly in digital consumer culture, has significant archaeological value. These cartridges were once worthless, but only because they symbolised corporate greed and overreach at the time.

The Atari story is more than a cautionary tale about the boom-and-bust of technological cycles. It warns about the dangers of unbridled optimism in the corporate space. The incident also shows how companies sought to cover up their perceived shame.