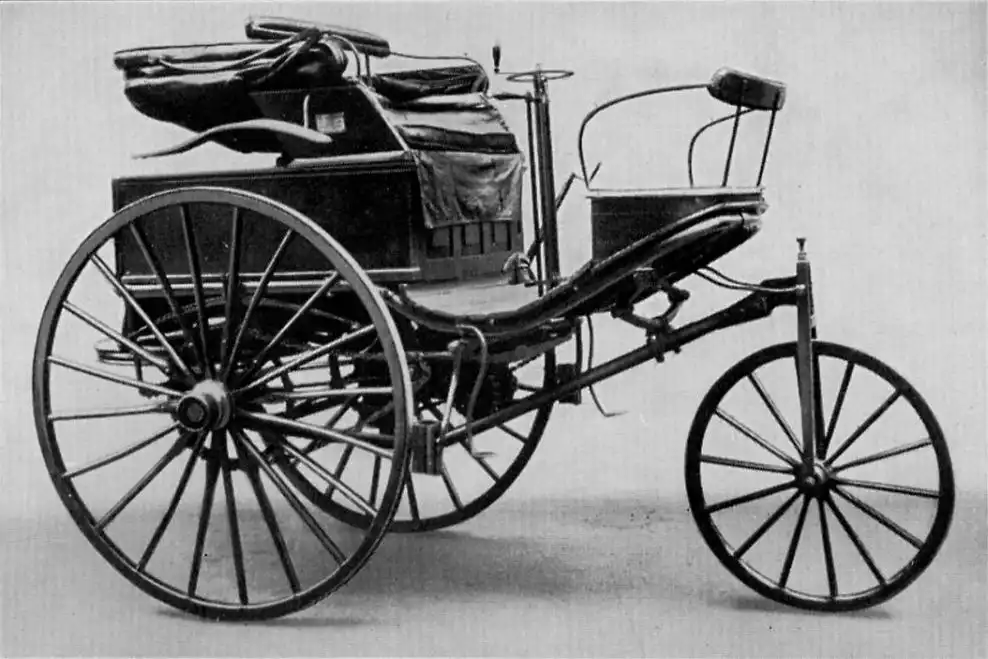

The earliest car did not resemble what we drive today. It had three wheels, no steering wheel, and a single-cylinder engine that wheezed out less than one horsepower. Karl Benz completed the Patent-Motorwagen in 1885. It ran on gasoline and depended on a series of levers and chains to keep it moving.

While Benz was focused on engineering, his wife Bertha made it famous. She took the car on a 66-mile trip in 1888 with her sons, buying fuel from a pharmacy along the way. She also fixed a broken fuel line with her hat pin. Her journey proved the machine could travel far and return home.

The Car Becomes a Product, Not Just an Invention

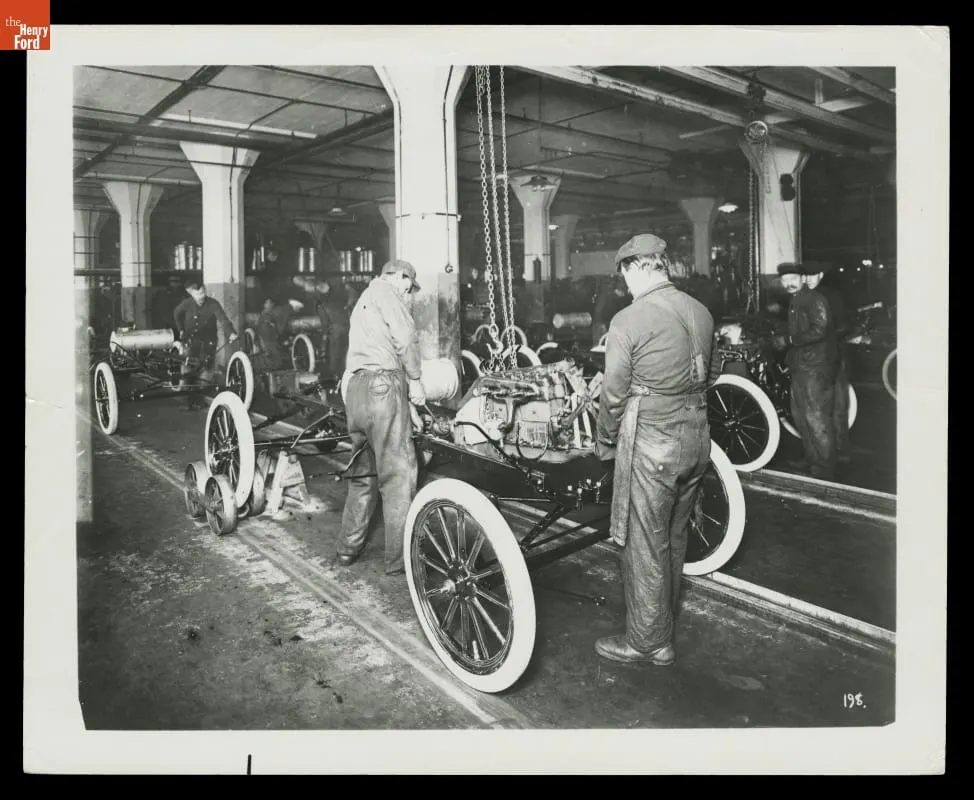

By 1908, the world was ready to drive. What it lacked was a car people could afford. Henry Ford solved that problem with the Model T. It was not fancy, but it started easily and held up on rough roads. It became a tool for farmers, mail carriers, and anyone with a little savings.

The key was Ford’s factory. Instead of building one car at a time, he brought the car to the workers. Each man added one part, again and again. This system cut the time to build a Model T from twelve hours to less than two. By 1927, Ford had sold over fifteen million units.

A New Symbol of Status, Speed, and Crime

In the 1920s and 30s, cars gained personality. The wealthy bought long, curved Duesenbergs. Ordinary people dreamt of Packards and Studebakers. Cities became louder as horns blared and engines roared. The road became a public theater of ambition.

Criminals noticed too. Getaway cars allowed bank robbers like John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde to escape across state lines. Bonnie’s poetry romanticized their Ford V8, but photographs told the truth. It was dented, bloodstained, and filled with bullet holes. It died with them on a Louisiana highway.

When War Stopped Style and Started Strategy

During World War II, American car factories stopped making cars for civilians. They produced tanks, Jeeps, and bombers instead. Chrome grilles were replaced with camouflage paint. Tires went to military convoys, not cross-country road trips.

One vehicle became a favorite: the Willys Jeep. It was boxy, fast to repair, and able to cross swamps and hills. Soldiers respected it. After the war, veterans brought the Jeep home. It soon became a civilian utility vehicle and set the stage for the SUV.

The 1950s Car Was Built Like a Rocket

The decade after the war was loud and optimistic. People moved to the suburbs, built highways, and turned drive-ins into weekend rituals. Car companies competed with each other by adding chrome, color, and flair. Tailfins reached absurd sizes.

The 1959 Cadillac Eldorado was the peak of this trend. It was longer than some city apartments and dripped with ornaments. Driving became a form of self-expression. Even station wagons began to look luxurious, with faux wood paneling and pastel paint jobs.

The Car Kennedy Rode Into History

In 1961, a unique car rolled off Ford’s production line. It was a black Lincoln Continental convertible with suicide doors and extra length. After delivery, it was sent to Hess and Eisenhardt in Ohio to become the presidential limousine. They extended the frame, added steps, and left the roof removable.

President John F. Kennedy used this car, called the SS-100-X, for parades and public events. It allowed people to see him clearly. On November 22, 1963, in Dallas, the roof panels had been removed. As the car passed through Dealey Plaza, shots were fired. The limousine kept rolling as Secret Service agents jumped aboard. Kennedy did not survive.

After the assassination, the same car was rebuilt. It received bulletproof glass, armor plating, and a fixed roof. It continued to serve later presidents under a different name. No vehicle before or since has carried the same weight in American memory.

Fuel Shortages Change the Shape of the Car

In the 1970s, the world experienced an oil crisis. Gas prices rose, and lines at the pump stretched for blocks. American carmakers had built vehicles that guzzled fuel. Now, buyers looked for something smaller and more efficient.

Japanese automakers offered the answer. The Toyota Corolla and Honda Civic were inexpensive, reliable, and easy to repair. American companies scrambled to catch up. The car shifted from being a loud expression of wealth to becoming a practical tool for survival.

Digital Begins to Replace Mechanical

In the 1980s, cars began to speak another language. Early onboard computers appeared. Digital speedometers and blinking indicators became common. Safety features also improved. Airbags were introduced. Anti-lock brakes started moving from race tracks to regular roads.

The DeLorean DMC-12 became famous through its stainless-steel body and gullwing doors rather than its performance. It was a flop in showrooms but a star on screen. In “Back to the Future,” it reached 88 miles per hour and became a time machine. It proved that the car had become more than a vehicle and had entered the imagination.

SUVs Rise and Minivans Retreat

By the 1990s, American families began to move away from sedans and station wagons. They wanted more space, more power, and a sense of command on the road. The Ford Explorer and Jeep Cherokee became the new family vehicles.

At the same time, computer systems inside cars grew more complex. Vehicles now monitored tire pressure, adjusted the suspension, and locked themselves. Mechanics learned to read error codes instead of listening to clanks. The bond between man and machine began to depend on software.

Hybrids Quietly Lead a Green Revolution

The early 2000s brought hybrids into mainstream garages. The Toyota Prius was quiet, aerodynamic, and unusually shaped. It combined gasoline and electric power. It became a favorite among celebrities and city dwellers. It also turned fuel economy into a public conversation.

Car companies began to compete on miles per gallon. Green became marketable. Hybrid versions of existing models appeared. Yet the engines remained internal combustion. The change had begun, but it had not gone far enough to shift the industry.

The Tesla Shockwave

Tesla launched the Roadster in 2008, but the Model S in 2012 changed everything. The Model S looked elegant, drove fast, updated itself overnight, offered space for seven, had no engine under the hood, and sold out quickly.

Drivers could now plug in at home, skip gas stations, and monitor their car from a phone. The Tesla was more than an electric vehicle; it functioned as a software platform. And as it gained autopilot features, the line between driving and riding began to blur.

The Car Learns to Drive Itself

As the 2010s progressed, cars began to help drivers in ways that seemed almost like intuition. Lane assistance, adaptive cruise control, and automatic braking appeared one by one. Sensors, cameras, and radar formed a digital cocoon around the car.

Full self-driving continued as a promise while partial autonomy entered daily life, making long highway trips feel easier and less demanding. Some cars could park themselves. Others prevented collisions before the driver even noticed the danger.

Electric Is No Longer Experimental

By the 2020s, nearly every major manufacturer had joined the electric race. Porsche built the Taycan. Ford turned its iconic Mustang into the Mach-E. Hyundai, Kia, Rivian, and even General Motors launched full electric lines. Charging stations spread across cities and highways.

Battery range improved and fast charging became viable, encouraging hesitant buyers to make the switch. Governments announced timelines to phase out combustion engine sales, marking a lasting shift in the history of the car.

Concept Cars Push Toward Science Fiction

Future designs now stretch imagination and material. BMW unveiled a color-changing vehicle while Hyundai introduced a walking car equipped with robotic legs. Inside these futuristic designs, seats respond with haptic feedback and windows transform into interactive screens. Artificial intelligence plays music based on mood and route.

While these vehicles remain concept-only, they show what may come. The car of tomorrow may not have a steering wheel. It may not need a driver. It may fly, fold, or even climb.

The Car Remains a Personal Machine

Despite all the changes in power, shape, and software, the car still plays an emotional role. People remember their first ride. They name their vehicles. They attach meaning to commutes and road trips. In some cases, they build lives around them.

A car is never just a machine. It is a container for stories, arguments, silence, and music. It connects places and people. And as long as it moves, it remains part of what it means to be human.