Before menus, before microwaves, before anyone said “I’m cutting carbs,” humans still had to eat. They foraged, cooked, soaked, boiled, and chewed their way through every kind of terrain and crisis. Food offered survival, carried meaning, demanded labor, and shaped identity. It connected communities to the land and to each other. This is the story of meals across centuries, served with a side of tools, textures, and forgotten flavors.

Charred Bones and Stone Soup

Before farming, before ovens or dishes, early humans ate whatever they could find, kill, or pull out of the ground. Meals came without recipes or rituals and carried only the urgency to survive. Prehistoric people hunted animals, cracked open bones for marrow, and roasted chunks of meat over open flames. The idea of “cuisine” had not yet formed. People scraped seeds into paste using grinding stones and cooked over hot rocks, creating food that was tough, fibrous, and slow to chew and digest.

Campsites often included communal fire pits where people brought roots, insects, and scraps to share. Flat rocks and large leaves served as makeshift plates, holding the meal with ease.

Grain, Beer, and the First Food Surplus

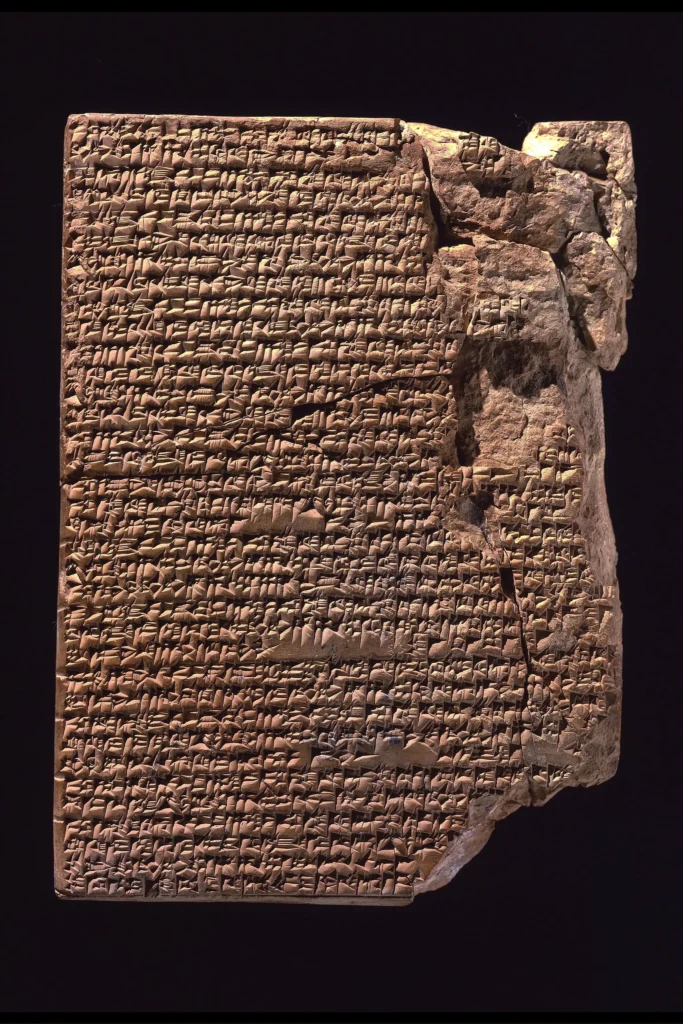

With the rise of agriculture, food became more predictable. In Mesopotamia, Egypt, and parts of the Indus Valley, people began growing barley, wheat, and lentils. They learned to store grain in clay jars and to ferment it into early beer. In many places, beer was safer to drink than water and more filling than broth. Babylonians wrote recipes on clay tablets. The earliest ones describe soups, stews, and a wide variety of ways to cook sheep.

Food was cooked in clay pots and served in shallow dishes. Most people ate with their hands. In some cultures, a spoon made from wood or bone was considered advanced.

Food Fit for Pharaohs and Slaves

In Ancient Egypt, diet depended on class. The elite had access to fruits, honey, and roast goose. Workers ate barley bread, lentils, onions, and beer. That beer was thick and murky, with floating grain still in it. Kitchen tools were basic. Most homes had a fire pit, a few jars, and a grinding stone. Bread was coarse and dense, baked in clay molds that often left ash and grit inside.

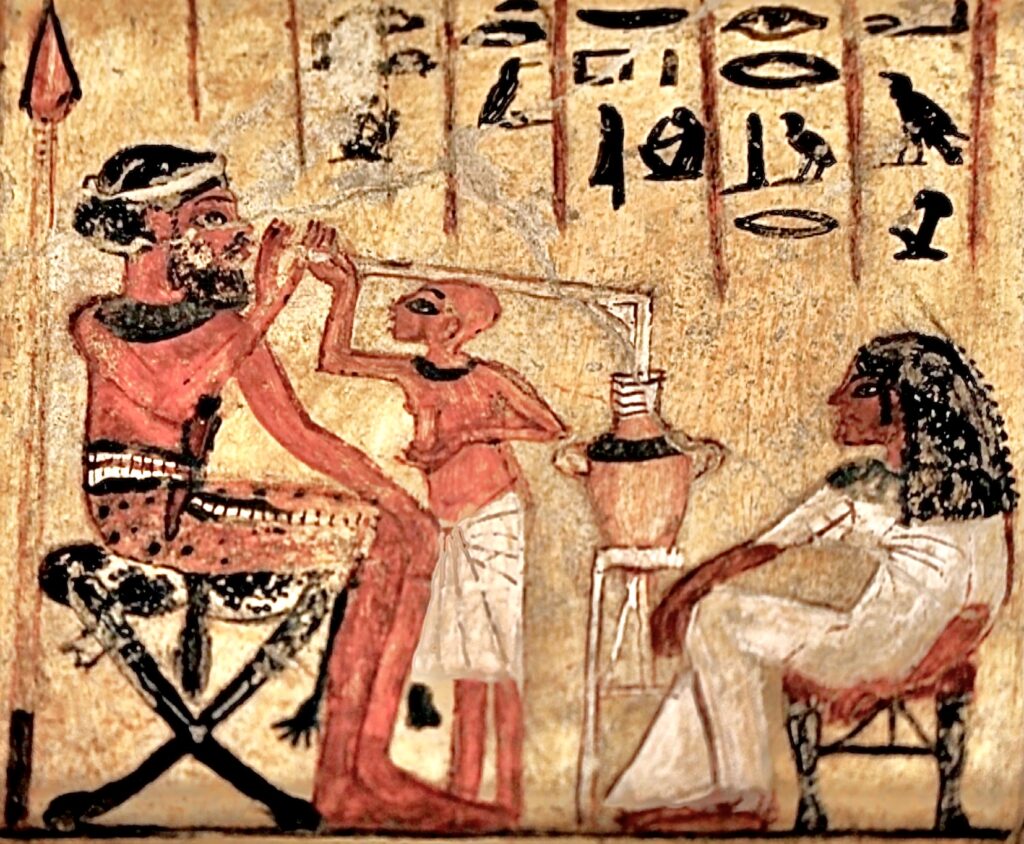

Tomb paintings show tables overflowing with figs, melons, fish, and folded cloth napkins. These images did not aim to document real meals. They portrayed aspirational offerings prepared to accompany the dead into the afterlife.

Rome Wasn’t Fed in a Day

Romans loved to eat in groups, reclining on couches and passing food with long-handled spoons. In upper-class homes, meals had many courses and included oysters, sea urchins, and stuffed dormice. Garum, a fermented fish sauce, appeared on nearly everything. Slaves prepared these meals in smoky kitchens using ceramic pots and bronze pans.

Street vendors sold simple food like bread, olives, and warm lentil stew to workers. Bakers made flatbreads in public ovens. In large cities, many homes did not have kitchens, so people ate out more often than in.

Forks Were Weird, So We Used Bread

In medieval Europe, most people did not own forks. Spoons, knives, and hands were enough. Meals were communal. A loaf of bread cut in half became both plate and food. This was called a trencher. When the meal ended, the soaked bread might be eaten or thrown to the dogs.

The wealthy dined on roasted meats, pies filled with fish or fruit, and molded jellies. Spices showed off social status. The poor ate boiled vegetables, grains, and broth. Pottage was the most common meal, a stew that sat over the fire all day and changed depending on what was available.

Salt Cod and Global Theft

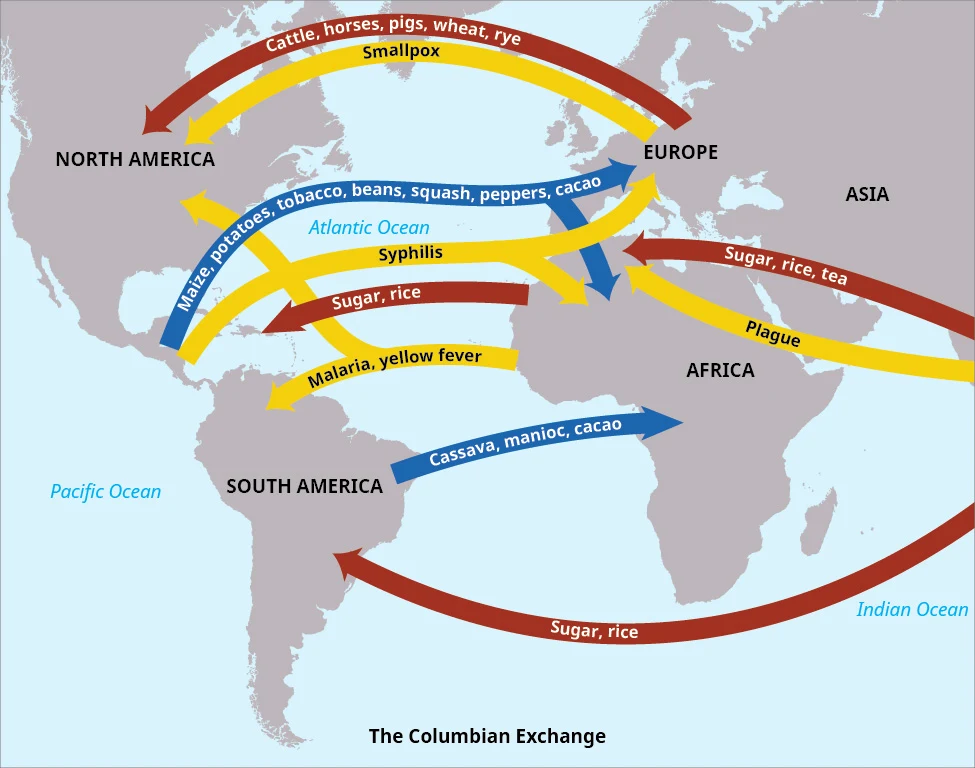

When Europeans began sailing across the world, food traveled with them. Potatoes moved from Peru to Ireland. Tomatoes went from Mexico to Italy. Chilies arrived in India from the Americas. The movement of plants and recipes reshaped entire cuisines. In many cases, people lost their traditional food systems to plantations, trade routes, and colonization.

Sailors lived on hardtack, salted fish, and dried beans. These foods lasted for months but had little flavor. Indigenous farmers who once grew maize, beans, and squash were pushed out of their lands. Their staple crops were harvested for export instead of local use.

Revolutionary Bites and Tea Protests

Food has often been political. During the American Revolution, colonists refused to drink tea. Coffee became the new symbol of independence. In France, rising bread prices fueled riots and protests. Marie Antoinette’s apocryphal cake remark captured the social divide between hungry people and overfed royalty.

In India, British officers demanded spice-rich curries while local cooks were paid very little. Meals were a reminder of power, with polished silver on one side and iron pots on the other.

Meat, Molasses, and Industrial Meals

The industrial revolution introduced canned food, factory-made bread, and molasses in bulk. In England, smog turned kitchens grey, but food sellers filled the streets with roasted chestnuts, fried fish, and meat pies. Milk often came watered down. Sugar became cheap and addictive.

Workers ate lunch from tin pails and brought home loaves of factory bread. Dinner might include boiled potatoes or cabbage. In upper-class homes, servants prepared formal meals on strict schedules with printed menus and dress codes.

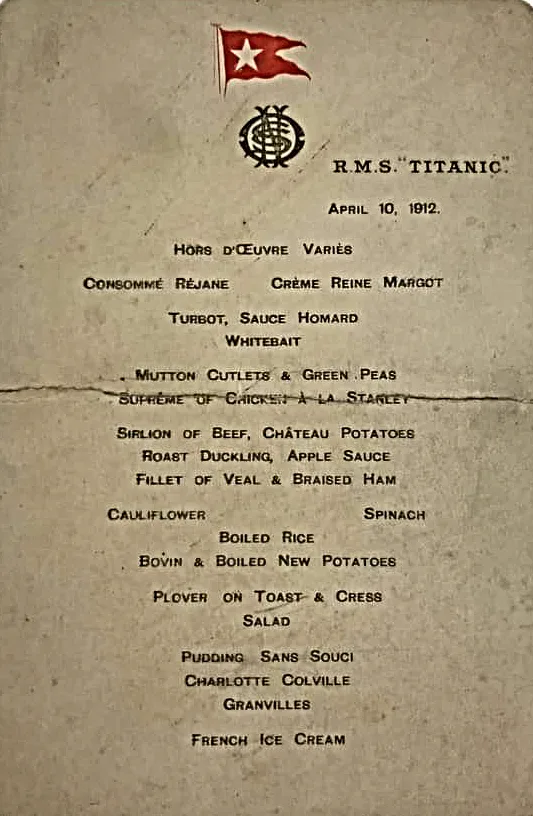

Titanic Menus and Workhouse Gruel

The first-class passengers on the Titanic ate oysters, quail, and peaches in chartreuse jelly. At the same time, children in English workhouses received watery porridge and stale bread. Menus told the story of class more clearly than anything else. Luxury was documented, photographed, and celebrated. Poverty remained invisible.

Cookbooks for the poor taught how to stretch flour and save fuel. Cookbooks for the rich focused on presentation and silverware placement. Food separated people more than united them.

Boiling Boots and Trench Stew

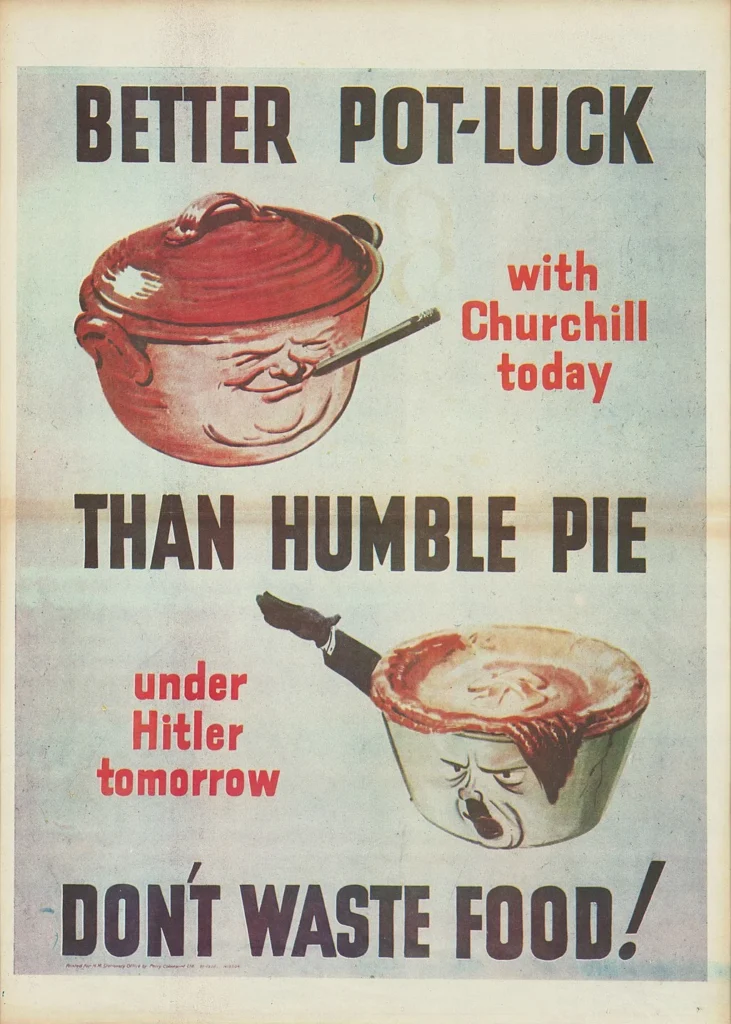

During wars, food became a matter of survival. Soldiers in World War I lived on biscuits and stew made from tinned meat and root vegetables. In some camps, supplies ran so low that people boiled leather shoes for broth. World War II brought ration books and government-issued recipes for carrot cake without sugar and meatless meatloaf.

Women grew vegetables in backyards and public parks. Schoolchildren learned to cook simple meals with powdered eggs and canned beans. Flavor mattered less than calories.

Plastic Trays and Frozen Peas

In the mid-20th century, convenience shaped the menu. TV dinners came in foil trays, complete with turkey, mashed potatoes, and a brownie. People no longer needed to cook from scratch. Supermarkets replaced open-air markets. Meal prep became a matter of opening boxes.

At school, children ate lunch from plastic trays with divided compartments. Government surplus ingredients turned into casseroles. Artificial flavoring replaced fresh herbs. Home economics classes taught meal planning using packaged foods.

Space Pouches and Edible Science

Astronauts needed food that could float, squeeze, and survive zero gravity. Tubes of applesauce and freeze-dried ice cream appeared. Early space meals were bland and difficult to eat, but they kept bodies functioning. In time, scientists introduced rehydrated meals, bite-sized snacks, and carefully measured calorie packs.

Space food required no smell, minimal crumbs, and maximum efficiency. It reflected function, not pleasure.

Food as Protest, Identity, and Home

For many communities, food preserved identity. African American families passed down recipes for cornbread, greens, and black-eyed peas. Jewish families shared matzah and kugel. Indian families handed down spice blends and oral instructions.

In times of crisis, food acted as resistance. Hunger strikes became political tools. Community kitchens fed protesters and sheltered refugees. Cookbooks preserved both flavor and memory.

What We Eat Now

Today’s meals span centuries. Flatbreads, noodles, and lentils appear on tables around the world, just as they did thousands of years ago. Food delivery apps coexist with fermented pickles and open-fire cooking. People still gather to eat, to talk, to share what they have.

Even in refugee camps, even after disaster, meals continue. Not because they are easy, but because they are essential.