Before alarm clocks, pest control companies, and public sanitation departments, entire professions existed to fix life’s weirdest problems. Some of them sound like TikTok dares today. But back then, they were legitimate careers with uniforms, tools, and in some cases, royal appointments.

Let’s take a trip through history’s most bizarre job listings. And yes, we have the photos to prove none of this is a joke.

Wake-Up Calls Were Delivered by Stick

In 1800s England, long before affordable alarm clocks were common in working-class homes, factory workers were still expected to start their shifts before sunrise, often by 5 AM. The solution was surprisingly low-tech: a person known as a “knocker-upper” who walked the streets each morning, tapping on windows with a long stick to wake people up.

Depending on their neighborhood or personal preference, knocker-uppers used different tools for the job. Some relied on simple bamboo rods to reach second-story windows, while others carried impressively long poles that extended almost the height of the buildings. In more densely packed housing areas, where disturbing the neighbors was a concern, some knocker-uppers used pea shooters, which were small tubes that launched dried peas at windows to create just enough noise to wake a single household without alerting the entire block.

Before Rentokil, There Was Jack Black

And this was not just another thankless job. Some rat catchers became local celebrities. Jack Black, for example, styled himself as the “Royal Rat Catcher” during Queen Victoria’s reign. He wore a custom jacket decorated with dead rats, posed proudly with cages full of live ones, and even gave public demonstrations of his technique.

The job itself required nerve and speed. Rat catchers worked in sewers, cellars, and shipyards, often crawling into cramped, infested spaces to catch rats by hand. Some used trained terriers or ferrets to flush them out, while others relied entirely on quick reflexes and thick gloves. A few turned their expertise into side businesses, breeding tamer varieties of rats and selling them as exotic pets to upper-class women who found them strangely fashionable.

It wasn’t glamorous. But it paid well, especially during plagues.

Leech Collectors Bled for the Job

Leeches were not just unpleasant to look at; they were a booming part of the medical economy. In the 18th and 19th centuries, doctors prescribed leeches for nearly every imaginable ailment, from cramps and headaches to fevers and infections. Some even believed leeches could balance the body’s humors or remove negative energy, making them a go-to remedy for both physical and emotional distress.

To meet the constant demand, someone had to collect them. That responsibility often fell to women known as leech collectors, who would wade into marshes, ponds, and bogs where the leeches thrived. They stood still in the water and allowed the leeches to attach themselves to their bare legs, then carefully removed each one by hand and placed it in a jar for sale. The job was exhausting, unsanitary, and often left collectors weak from repeated blood loss, but it was steady work in a time when few options existed.

They Ate Your Sins Literally

In 17th-century England and Wales, particularly in rural areas, it was not unusual for grieving families to hire someone known as a sin eater to perform a final, unofficial ritual. This person’s role was to absorb the sins of the deceased, ensuring that the soul could pass into the afterlife unburdened.

The process was both symbolic and deeply unsettling. The sin eater would sit at the foot of the corpse, and a piece of bread or a simple meal would be placed directly on the body, often across the chest. After reciting a short prayer or chant, the sin eater would eat the food, which was believed to have drawn in all the sins the person had carried through life. By consuming it, the sin eater was thought to take those sins into himself.

Despite performing a task many considered necessary for the salvation of the dead, sin eaters were often treated as outcasts. They usually came from the poorest communities and had few other means of survival. People believed that each time they consumed a soul’s sins, they became more spiritually contaminated. Even so, when someone died and the family feared for their loved one’s soul, they turned to the sin eater to carry away what no priest or ritual could remove.

When Toilets Didn’t Flush, These Guys Got Paid

Gong farmers in medieval Europe and Asia held one of the most unpleasant yet essential jobs in urban life. They were responsible for removing human waste from cesspits, which collected the contents of chamber pots and primitive toilets beneath homes and public buildings.

Using buckets and shovels, they would climb into the pits and haul the waste out by hand, transferring it to carts or barrels for disposal outside the city. Because the work was so foul and the smell so overpowering, most gong farmers operated at night, both to avoid disrupting daily life and to shield themselves from public scorn. Their profession was considered so offensive that they were often banned from entering taverns, churches, or walking openly through certain streets during the day. Despite the stigma, the job paid relatively well, largely because no one else wanted to do it.

Fish Got First-Class Treatment

In 19th-century London, especially around Billingsgate Market, fish porters were hired to carry large baskets of fresh fish on their heads from the docks to the market stalls. These baskets were often packed to the brim and sometimes still held live fish, making them heavy, unsteady, and difficult to manage on crowded streets.

The job involved walking long distances through busy lanes filled with people, carts, and animals. Porters needed strong backs and good balance to keep the load steady. The smell of fish stayed with them all day, and their clothes were often soaked with water from the baskets.

Working nearby were the fishwives, who cleaned and sold the fish to customers. They were known across the city for their loud voices, sharp words, and quick tempers. They called out prices, argued with buyers, and shouted at anyone who got in their way. The energy of the market came as much from their noise as from the work itself.

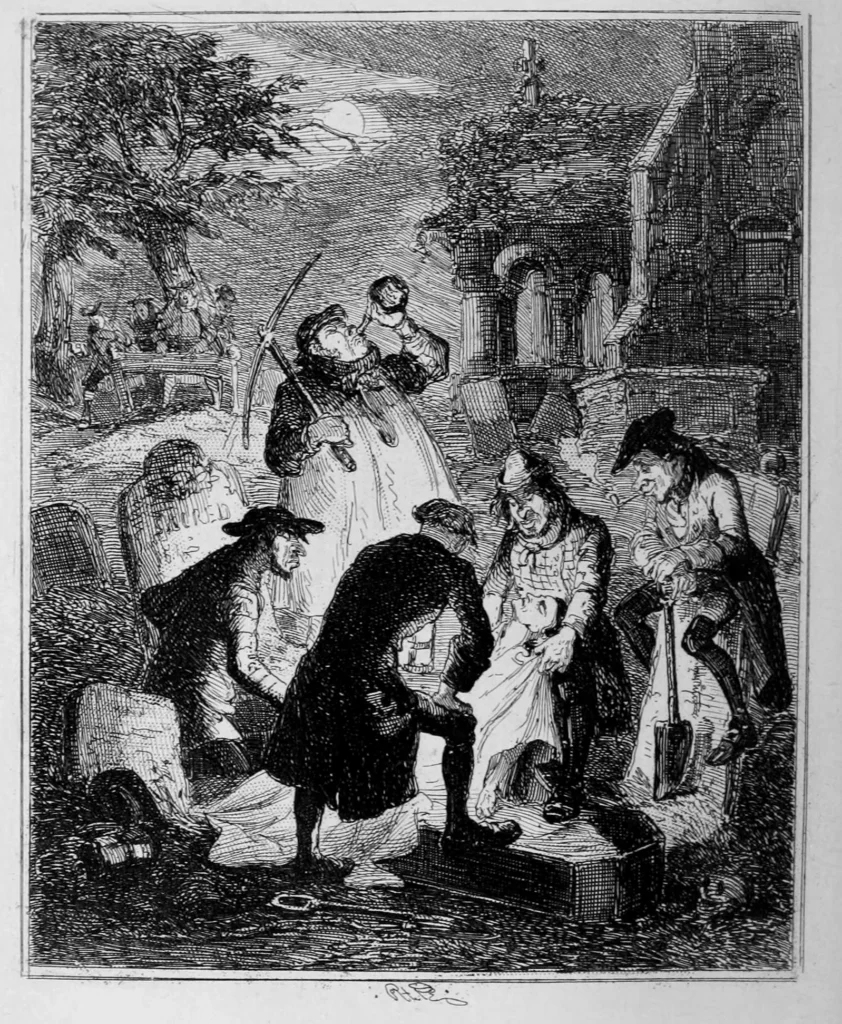

Grave Robbing Was an Academic Career

When medical schools in the 18th and early 19th centuries needed cadavers for anatomical study, but religious and legal restrictions made it difficult to obtain them legally, they turned to a group of men known as resurrectionists. These were professional body snatchers who specialized in digging up freshly buried corpses and transporting them to universities, often under the cover of night.

Resurrectionists worked quickly and quietly, targeting graves that were no more than a day or two old. They often operated in teams and used simple tools to avoid drawing attention. Their clients were professors and surgeons in places like Edinburgh and London, where the demand for bodies far outpaced the legal supply from executed criminals.

Although grave robbing was technically a misdemeanor and not classified as a felony, public outrage was fierce. Families built iron cages over graves, hired guards, and set traps to protect the dead. Even so, resurrectionists continued their trade, driven by the steady pay and a system that quietly relied on their work.

The most infamous names associated with this world were Burke and Hare, who began supplying bodies to Dr. Robert Knox in Edinburgh. Unlike typical resurrectionists, they eventually skipped the grave robbing altogether and started killing vulnerable lodgers to meet the demand. Their case sparked public fury and led to the Anatomy Act of 1832, which allowed medical schools legal access to unclaimed bodies from hospitals and workhouses.

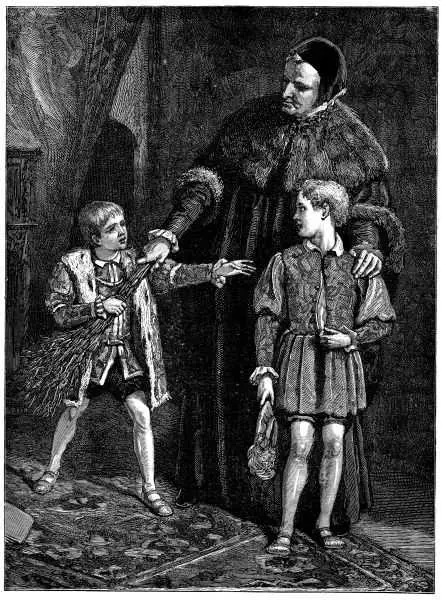

Royal Kids Didn’t Get Hit Because Their Friends Did

In certain royal households, it was considered inappropriate to punish a prince directly because of his noble status. Discipline was still expected, so the consequences were handed to someone else. This led to the creation of a position known as the whipping boy.

The whipping boy was typically another young boy, raised alongside the prince from an early age to form a strong personal bond. When the prince misbehaved or defied his tutors, the whipping boy would be punished in his place. The idea was that watching a close companion suffer would encourage the prince to correct his own behavior.

Although the arrangement was undeniably unfair, some whipping boys eventually gained favor for their loyalty. A few were granted land, titles, or lifelong positions within the royal court after growing up beside the future king.

You Got the News from a Bell and a Shout

Town criers were once the main source of public information in cities and villages, long before newspapers or radios existed. Dressed in distinctive uniforms and carrying a bell to grab attention, they walked through the streets announcing everything from local deaths and tax changes to royal decrees and wartime news.

Each announcement began with a loud call, often the word “Oyez” repeated three times, to signal that important news was about to be shared. The messages they delivered were considered official and legally binding, which meant everyone was expected to listen, even those who could not read.

Being a town crier was not simply a job but often a lifelong role. In many communities, the position was passed down through families or held by a single person for decades. One man in England continued as town crier for over fifty years, becoming a familiar and trusted voice throughout his town.

These jobs may seem strange now, but each one served a purpose. Someone had to wake the town before alarms existed. Someone carried waste through narrow streets before plumbing was built. Others caught rats, watched over royal children, balanced fish baskets on their heads, or shouted the news in public squares.

They were part of the everyday rhythm that kept cities running. Their efforts made it possible for modern systems to take shape. Although their titles faded over time, the work they did continued in new forms.

The next time you hear your alarm, turn on a faucet, or read the news on a screen, pause for a moment. Somewhere in that comfort, a knocker-upper, a gong farmer, or a rat catcher once did it by hand.