By the time most kids were learning cursive, Barbara Newhall Follett was signing a publishing contract.

At just twelve years old, she’d finished her first novel. It was called The House Without Windows, and it stunned adult readers with its lyrical prose and haunting imagination. She wrote about a girl who abandons the world to live among nature, to vanish into something larger, softer, and quieter than the noise of human life.

A child with too much to say

Barbara was born in 1914 in New England, the daughter of critic and editor Wilson Follett. Her home was full of books, ideas, and long walks in the woods. She never went to a traditional school, but she didn’t need one. Her mother taught her, encouraged her, and watched as her daughter began building elaborate fantasy worlds out of thin air. By the time she was nine, Barbara had created an imaginary country called Farksolia, complete with its own language and alphabet.

Her father, an editor at The Atlantic Monthly, took note. He saw genius and decided the world should, too. He edited her debut and helped publish The House Without Windows in 1927. Reviews were not patronizing. They were awestruck. People were fascinated to know a child had written it.

She went to sea and brought back a second novel

After the attention from her first book, Barbara didn’t settle down or go off to boarding school like a proper literary girl from a well-off family. She went sailing. With her mother and later with a small crew, she lived on boats, navigating the coast of Nova Scotia and the Caribbean. She loved the sea and hated civilization. She believed adventure was the only real teacher.

From those travels came her second novel, The Voyage of the Norman D. Published in 1928 when she was just fourteen, the book was a mix of memoir, sea yarn, and existential musing. It was thoughtful, witty, strange. It was also, again, ahead of its time.

That’s when things began to fall apart.

The world didn’t know what to do with her

Her father left the family.

Barbara’s emotional anchor was gone, and with him went her literary momentum. The Depression hit, and publishers weren’t so quick to take risks on young, unproven writers, even one with two books already in print. Her third novel, Lost Island, wouldn’t be published during her lifetime.

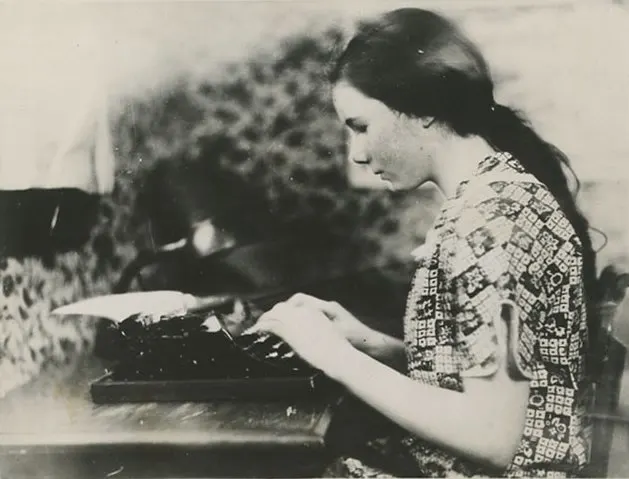

She took odd jobs such as a secretary, typist or a proofreader. She married a man named Nickerson Rogers, who seemed charming at first but would eventually become the last person to see her.

Even as her world shrank, Barbara never stopped writing. She filled her journals and letters with raw, aching entries about feeling lost, unheard, and buried beneath the ordinary. She still dreamed of publishing. Of writing something that mattered.

But something in her had begun to pull away.

Then one day, she left

On December 7, 1939, Barbara walked out of her apartment in Brookline, Massachusetts after a fight with Nick. She had some cash on her and a small bag. That was it.

It was like one of her stories had swallowed her whole.

Her husband waited two weeks before reporting her missing. When pressed later, he said she had taken sleeping pills before. That she had been “unwell.” That she had left once before but always returned. But this time she didn’t.

Her mother never stopped looking.

Over the years, Barbara’s story has become a niche obsession for literary sleuths. She’s filed away as a “lost genius” or a “missing person.” But she was more than a vanished woman. She was a force of imagination in a world that never quite knew how to hold her.

ALSO READ: How a 25-Year-Old Survived the Alabama Wild With Nothing But Her Will

The bones in the woods

In 1948, nearly a decade after Barbara disappeared, a hunter discovered a partial skeleton in a hollow on Pulsifer Hill, near Holderness, New Hampshire along with some clothing fragments, a purse, a makeup compact and a pair of tortoiseshell glasses.

The site near Squam Lake, where Barbara and Nick had once camped and hiked during the early days of their marriage. Local police thought the bones belonged to a woman named Elsie Whittemore who had gone missing from nearby Plymouth in 1936. Elsie was pregnant and, allegedly, mildly depressed. Investigators suspected an intentional overdose, noting the presence of an empty medicine bottle nearby.

But nothing quite fit.

Elsie’s family didn’t recognize the belongings. The clothes were off. The shoe size didn’t match. She’d never worn glasses, they said. The police insisted it was her anyway and quietly closed the case.

No official ID was ever made and no certificates was issued. The bones were labeled “Holderness Female 1948” and eventually disappeared into bureaucratic fog.

Then someone started asking the wrong questions.

What if the woman in the woods wasn’t Elsie?

A writer researching Barbara’s disappearance stumbled across the Holderness skeleton while digging through old records. The location matched. The timeline matched. Barbara’s letters referenced a farmhouse in the same area that she and Nick had rented as a skiing base. She had spent time on that very hill. She knew those woods.

And the glasses? Barbara wore glasses. A Brookline police report from 1940 confirmed it. She also used barbiturates to sleep, something also found near the remains. Her height, previously recorded as 5’7″, was far closer to the re-estimated stature of the skeleton than Elsie’s 5’2″.

Even more chillingly, Barbara’s final novel, Lost Island, ends with the protagonist clinging to a pine tree, confronting the quiet horror of being forgotten. The last lines of her debut novel describe a girl dissolving into nature, leaving behind her human body forever.

The farmhouse on the hill

The piece that changed everything was the farmhouse.

Barbara had written about it in her letters. A lonely, dilapidated house owned by a prosperous farmer. A place they rented for absurdly low rates. She never said exactly where it was, only that it was near Squam Lake.

Years later, that same writer identified a property on the Campton side of Pulsifer Hill — less than half a mile from where the bones were found — that matched her description. It was known locally as “the White House.” And strangely enough, it had a second connection: Elsie Whittemore’s in-laws owned it years later.

But it didn’t stop there.

Barbara’s husband, Nick, later filed for divorce not from Massachusetts but from Campton, New Hampshire. He claimed to have lived there since December 1940, exactly three years after Barbara’s disappearance. New Hampshire law required a three-year absence to claim desertion. Whether he timed it intentionally, or the location had another meaning, is unknown.

Court filings casually mention that Barbara and Nick had lived in Campton “briefly in the summertime.” It all circles back to the same hill, the same woods and the same hollow.

And maybe, the same woman.

She was already slipping away

Barbara Newhall Follett was not the type of person to be absorbed into suburbia. Her stories always ended on mountaintops or under strange stars. She didn’t want to be saved. She wanted to be seen.

Maybe she made it to the farmhouse. Maybe she watched the snow fall through the window. Maybe she sat beneath that pine tree, took her sleeping pills, and let the forest take her back.

What remains is not her body, but her words.

Her letters. Her stories. Her books that still feel like they were written by someone who stepped sideways out of time. She may have disappeared in 1939, but she had already been leaving for years.

And if you read The House Without Windows closely enough, you might start to wonder whether Barbara Follett ever really wanted to stay.

Special thanks to Stefan Cooke, founder of Farksolia.org, for granting permission to use images of Barbara Newhall Follett and for his dedicated work preserving her legacy.