In an era when the term “over-the-counter remedy” could quite literally mean picking up a piece of a deceased neighbor, Europe indulged in a peculiar medical practice: consuming human remains to cure ailments. Yes. Our ancestors believed that the path to health was through ingesting bits of the dearly departed. From the 11th to the 19th centuries, medical cannibalism was a widespread therapeutic approach endorsed by physicians, royalty, and commoners alike. So, let’s embark on a journey through this horrifying chapter of medical history, where the prescription for a headache might have been a spoonful of powdered skull

How Europe Ended Up Eating Its Own

To understand how corpse consumption became medicinal best practice, you have to look at the social and medical landscape of Europe from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance and beyond. Plague outbreaks, incurable diseases, and war left loss in everyone’s backyard, and science had few tools to fight back. Physicians had no germ theory, no understanding of infections, and very little in the way of effective treatment.

Into this medical vacuum stepped philosophy. The Galenic model of humors and the Doctrine of Signatures filled the gap between ignorance and hope. If something looked like a human organ, perhaps it could heal that organ. And what better source of potent healing energy than another human?

Medical historian Richard Sugg, author of Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires explains, “The question was not, ‘Should you eat human flesh?’ but, ‘What sort of flesh should you eat?’”

Mummies, Fat, and Blood

The body was broken down into medicinal components with surprising specificity. Each part was believed to have its own therapeutic powers. Need help with a migraine? Powdered human skull was your go-to. Feeling anemic or afflicted by seizures? A warm glass of fresh human blood might do the trick. Suffering from joint pain? Rub on a salve made from the fat of an executed criminal. Struggling with erectile dysfunction? Ground-up mummified flesh was sometimes prescribed as a cure.

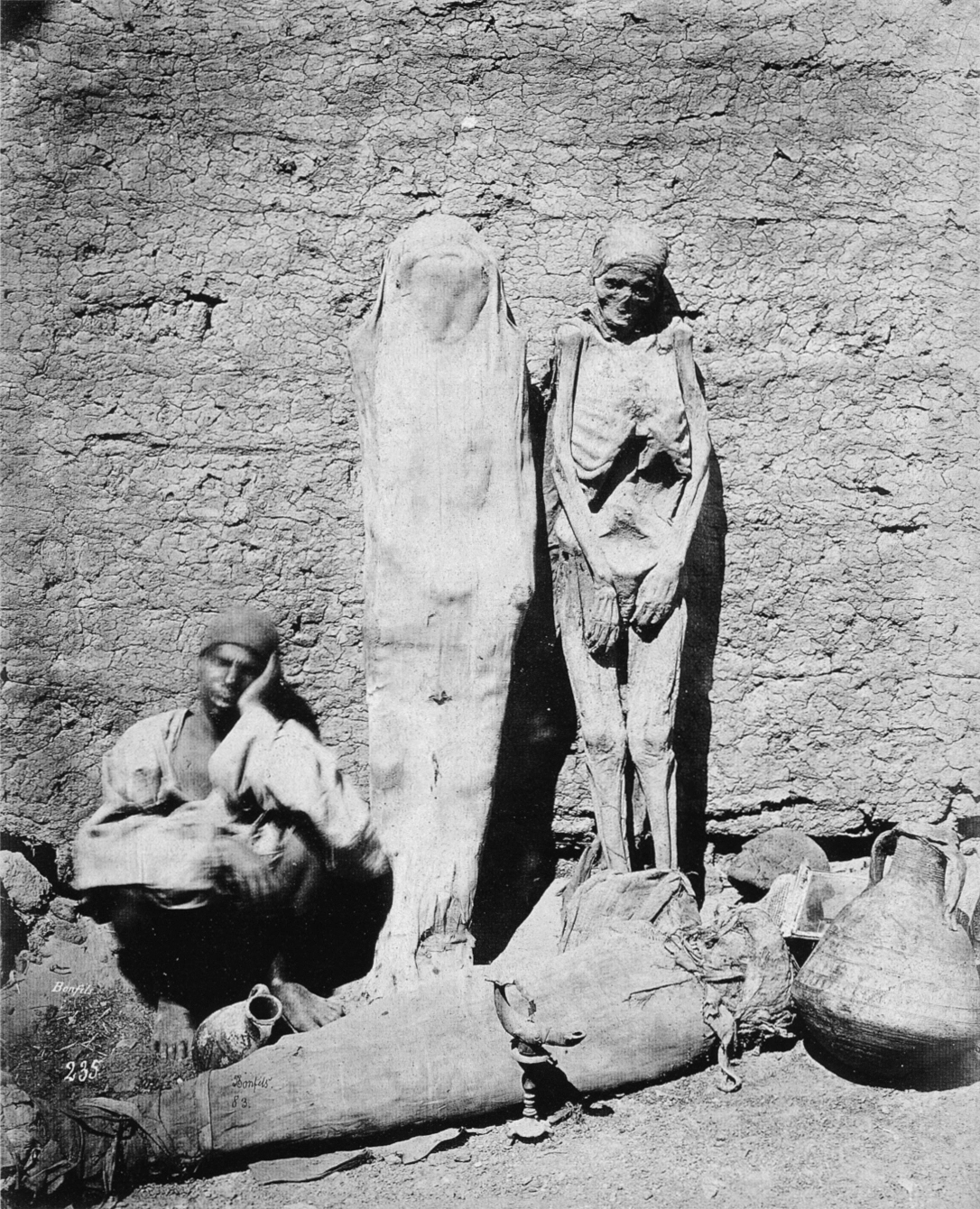

One of the most popular substances was mummia, which, originally referred to natural bitumen (a substance produced through the distillation of crude oil) used in Middle Eastern embalming. But thanks to centuries of mis-translation and cultural confusion, European apothecaries began using the word to describe powdered Egyptian mummies. Demand skyrocketed. According to the Science History Institute, European traders began importing mummies from Egypt by the ton. Apothecaries sold powdered corpses like modern-day painkillers.

Eventually, the supply of genuine ancient mummies couldn’t keep up with demand. Enterprising merchants started faking them using the bodies of criminals, slaves, or the poor. The Smithsonian Magazine notes that many were artificially embalmed and sold under the guise of ancient relics, creating a corpse-for-cash pipeline from graveyard to pharmacy.

Blood was another best-seller, preferably fresh, and ideally from someone who died violently. It was believed that the vitality of the executed was transferred through their blood. According to National Geographic, attendees at executions sometimes carried cups to collect the blood as it dripped from the scaffold. It was a grim scene, but perfectly normal for the time.

Skull powder, known as cranium humanum, was believed to stop internal bleeding and cure “falling sickness,” a catch-all term for neurological conditions like epilepsy. King Charles II famously took “The King’s Drops,” a concoction made from crushed skulls dissolved in alcohol, believing it kept his royal constitution strong. As odd as it seems, he was following medical advice, not indulging in royal eccentricity.

Even human fat had a niche market. It was applied externally to soothe muscle pain or rubbed on wounds to promote healing. Executioners became unintentional pharmacists, selling fat from the deceased for salves and ointments. Louise Noble, in her study Medicinal Cannibalism in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, confirms that this was seen as both practical and profitable.

ALSO READ: Victorian Women Swallowed Worms to Stay Thin

Why Nobody Found This Gross (Yet)

It’s tempting to dismiss all this as superstitious barbarism, but Europeans didn’t see it that way. Their worldview made corpse medicine completely logical. The body was a vessel of divine energy, capable of transmitting healing force even after passing. If a person had died young or violently, that energy was thought to be particularly potent.

Religion didn’t stand in the way either. In fact, many believed it was God’s will to make use of the departed. The body was temporary; the soul had already moved on. Using flesh to save a life was a noble act, not a disrespectful one.

And culturally, cannibalism was considered something “savages” did, not civilized Europeans. By framing their practice as medical, not culinary, Europeans were able to dodge the moral question entirely. Philosophers like Paracelsus argued that life essence persisted in the body after life had ended. Francis Bacon praised corpse-based treatments as potent remedies. Even during the Enlightenment, some doctors clung to corpse medicine, citing “empirical evidence” that the powders and tinctures had helped patients. Of course, without modern trials or controls, placebo effects likely did most of the work.

The Slow End of Cannibal Medicine

So, what finally brought medical cannibalism to an end?

By the 18th century, enlightenment thinkers began to apply reason and ethics to medicine. The growing understanding of disease transmission made the idea of consuming human remains seem not only immoral but unhygienic. New discoveries in anatomy, microbiology, and pharmaceuticals offered better alternatives, reducing the need for corpse-based cures.

Still, the decline of corpse medicine wasn’t immediate. Some practices lingered into the 19th century, especially in rural areas. The last known medicinal use of the human skull in Germany was recorded in the early 1800s. By then, science had mostly moved on, and public opinion followed.

But it left a stain: a dark, often overlooked chapter of medical history that’s equal parts fascinating and horrifying. The idea that Western medicine once relied on the bodies of the departed to cure the living is rarely taught in classrooms. Perhaps because it challenges the idea that civilization and morality always move forward in neat, linear fashion.

Medical cannibalism might seem unthinkable today, but its history forces us to confront uncomfortable truths. How easily do we justify ethics when desperation creeps in? As Richard Sugg points out, “The human body has been one of the most potent sources of healing in Western history.” That might make us squirm now — but for centuries, it made perfect sense. So next time you gripe about the taste of cough syrup, take a moment to be grateful. At least it’s not laced with powdered mummy.