I was writing in my daily diary one day when I accidentally flipped to the very first page, the one where I had written my New Year’s resolutions. As I looked through my old notes, one line caught my eye: “lose weight.” Like many people, especially women, this goal seemed less like a personal decision and more like something society had ingrained in us from a young age. And hence this article.

The origins of dieting

The story of dieting begins long before modern gym routines and calorie-counting apps. In ancient civilizations, concerns about food, body image, and health were part of everyday life but they looked very different from our modern perspective. The earliest ideas about being “fit” and “healthy” originated in Greece. The ancient Greeks were passionate about fitness, believing that a healthy body was a reflection of a healthy mind. Their approach wasn’t about having a slim figure but about achieving physical excellence.

It is interesting to note that while the Greeks focused on the function of the body, there was little emphasis on the visual aesthetics that we often see today. In their view, physical prowess and well-being were intrinsically linked, and dieting was simply a means to ensure longevity and vigor.

As centuries passed, the concept of dieting began to shift. The first diet book was published in 1558 by Italian Luigi Cornaro in his work The Art of Living Long. Cornaro’s advice was radical for his time: he recommended that his readers limit themselves to just 12 ounces of food a day and 14 ounces of wine. His suggestions were based solely on health, preserving one’s vitality and extending life were the primary motivations behind his strict regimen. The idea of a “perfect body” was not yet linked to visual appearance or societal trends. Instead, food restriction was a personal endeavor aimed at maintaining health and preventing disease.

By the mid-1800s, dieting had taken on a new, more complex role. It began to be used as a means of social and even racial signaling, particularly among men. During this era, the concept of an “ideal body type” started to emerge. Previously, a little extra weight was considered a sign of prosperity and good health.

Early advice manuals for gentlemen warned against overindulgence, labeling overeating as “unmanly.” This may sound odd today, but in the 19th century, the act of dieting was often framed as a mark of masculinity. Men were encouraged to adopt a diet that featured red meat, greens, fruits, and even dry wine, a regimen that was seen as a way to project strength and superiority.

In 1863, William Banting’s popular booklet Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public, provided a detailed plan for weight loss that emphasized a strict and disciplined approach. His diet became a bestseller and was celebrated as a model of masculine self-control and even racial superiority.

Interestingly, while men were adopting these rigorous dietary practices to assert their dominance, women were largely excluded from this initial wave of dieting. In many ways, dieting in the 19th century was seen as a “man’s problem” until, that is, women began to rebel against traditional expectations.

ALSO READ: Why Ancient Workers Couldn’t Build the Pyramids Without Beer

How Did Women Start to Reclaim Control Over Their Bodies?

For a long time, dieting was not really a concern for women. Early diet journals and manuals dismissed women’s eating habits. An 1865 issue of Harper’s Weekly, for example, complained that overweight young women were too preoccupied with finding romantic partners to worry about dieting. At that time, plumpness was actually associated with positive qualities like motherhood, respectability, and even sexual availability. Thinness, in contrast, was often linked with infertility. In a text from 1893, it was suggested that women should naturally eat less after turning 45 because their ovaries “shrivel up” and no longer require as much fuel. Women aren’t just eating for daily energy, they’re fueling their ovaries for baby-making, aren’t they, dear Victorian doctors!

However, as the century progressed, women began to assert their independence and demand the same kind of self-control that had long been celebrated in men. This period marked the beginning of a slim craze among women, a rebellion against the idea that only men could exercise self-control through dieting. As more women began to challenge traditional norms, the concept of dieting started to shift from a health necessity to an aesthetic pursuit. By the late 19th century, dieting had become a craze for women, transforming into a tool of both bodily control and self-expression.

The Victorian Ways of losing Weight

As the dieting crazerose in the 19th century, the methods used to achieve a slender figure grew increasingly extreme. As the ideal body type shifted toward thinness, both men and women began to adopt more drastic measures to conform to societal expectations. The public became fascinated with bizarre techniques and radical diets, some of which were downright dangerous.

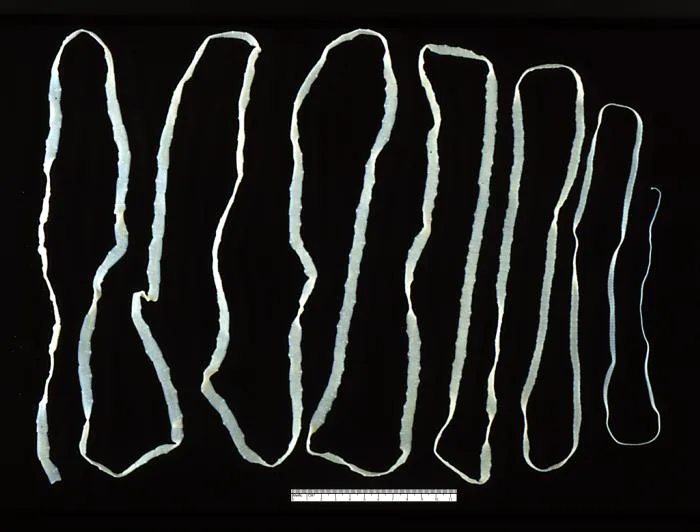

One of the most notorious examples of this extreme approach was the tapeworm diet. The concept was simple albeit gross. Dieters would swallow a pill containing tapeworm eggs, with the hope that the parasite would hatch, grow in the intestines, and absorb some of the nutrients from the food consumed. In theory, this would lead to weight loss without the need to reduce food intake. In practice, it was a risky and often harmful method. Tapeworms could grow up to 30 feet long and were known to cause serious health complications, including diarrhea, vomiting, and even neurological issues such as headaches, eye problems, and in extreme cases, meningitis or epilepsy.

It wasn’t just the tapeworm diet that showcased the lengths to which people would go. At the turn of the 20th century, the “chew and spit” method popularized by American Horace Fletcher, also known as Fletcherism became another extreme fad. This method required people to chew food meticulously (a single shallot was said to need 700 chews) to extract all its “goodness” and then spit out the remaining fibrous material.

Impact of Media and Celebrity on Dieting Trends

No discussion of dieting history would be complete without considering the role of media and celebrity culture. As print media expanded in the 19th century, diet manuals, beauty guides, and health journals reached wider audiences, further embedding the idea that dieting was essential for both health and beauty. Publications such as Harper’s Weekly and beauty guides like The Ugly-Girl Papers propagated the notion that maintaining an ideal figure was not just a personal choice but a societal duty.

For example, one guide emphatically declared that “it is a woman’s business to be beautiful,” reinforcing the idea that women must invest time and energy in elaborate beauty regimens to secure a favorable social standing. This narrative not only bolstered the popularity of dieting but also created a feedback loop where celebrity and media endorsements drove the adoption of extreme diets. Figures like Lord Byron, whose unique eating habits became the talk of the town, set trends that resonated even in modern times.

Today, we see this phenomenon in celebrity-endorsed diets and social media influencers, proving that the allure of a quick fix and the promise of a perfect body never really fades away.