All the trouble began with the organisers’ understanding of hydration. The race was organised in the suffocating summer heat on unpaved roads, chosen partly because officials wished to observe the effects of “intentional dehydration” on the human body.

To do this, runners were provided with just one water source along the entire course at the 12-mile point, upon the express orders of the Games director, a staunch believer in the dehydration theory.

1904 St. Louis Olympic marathon was an Olympic experiment gone berserk

The race was held in the afternoon, under the scorching sun at 3 p.m., contrary to today’s marathon schedule, which sensibly takes place in the early morning hours to avoid the day’s worst heat. Although marathon distances had not yet been standardised, the St. Louis marathon course was 24 miles and 1,500 yards, close to the modern 42.195 kilometres.

The route proved unstable. Originally set to pass through Creve Coeur, the course was changed at the last minute due to heavy rain on the planned route, leaving the runners little time to prepare. The result was a running path resembling an obstacle course. Runners found themselves dodging cross-town traffic, delivery wagons, railway trains, trolley cars, and even pedestrians walking their dogs, all of whom had not been cleared prior to the event.

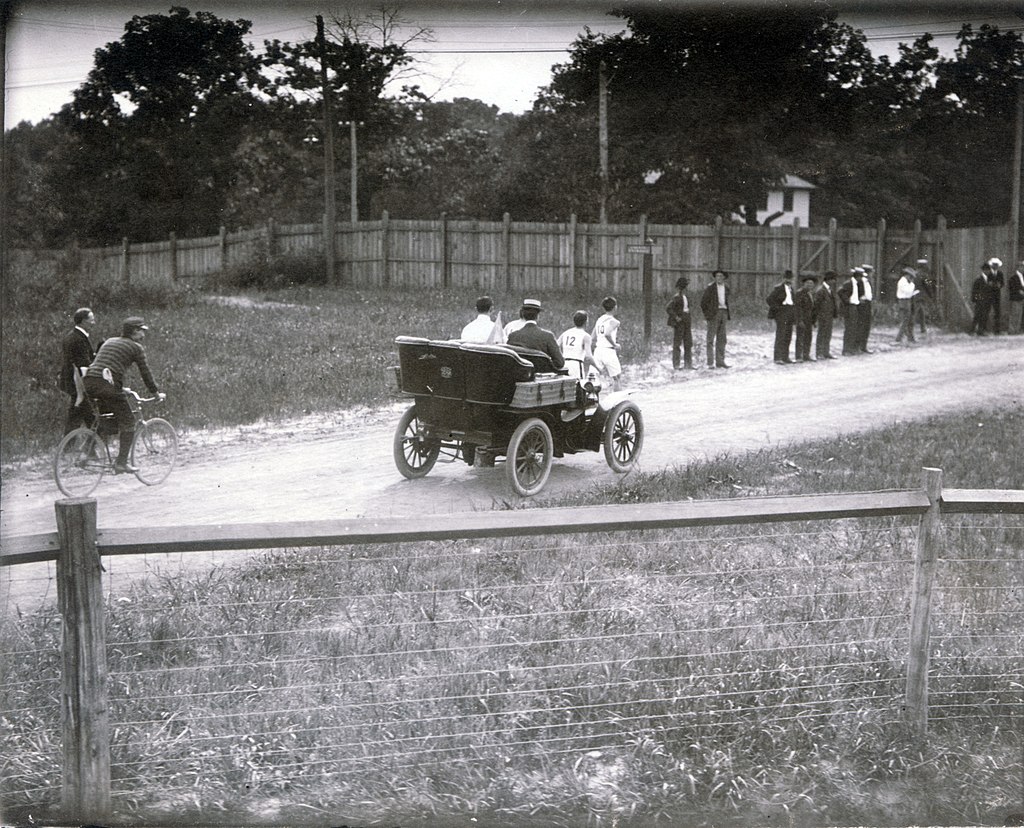

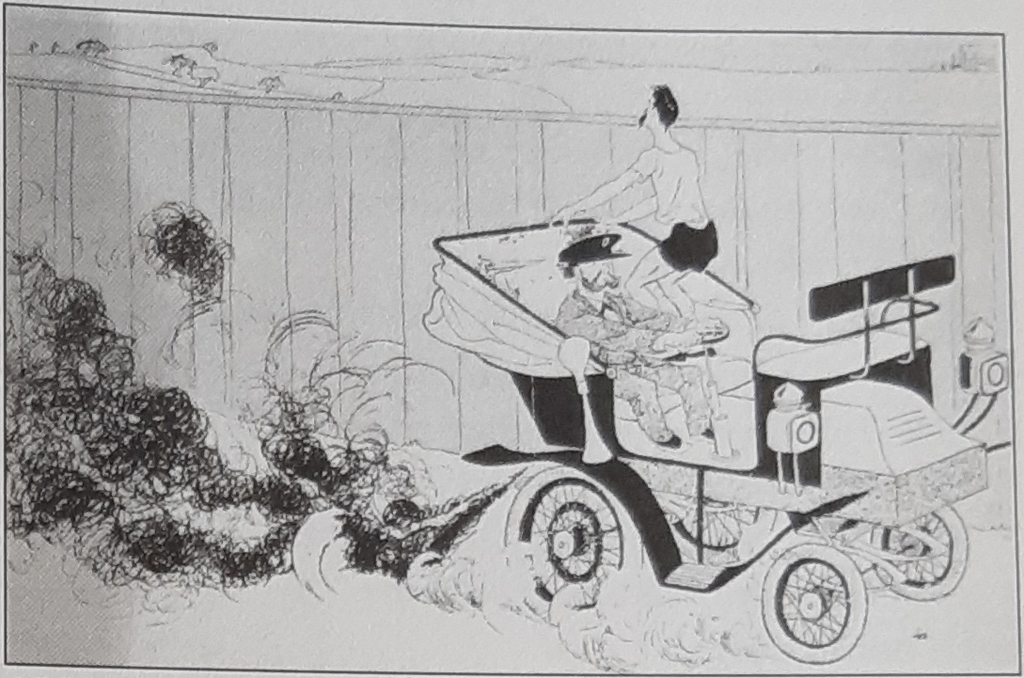

The opening segment consisted of five laps of about 1 2⁄3 miles around the stadium track, before the competitors were released onto dusty country roads. There, race officials followed in automobiles ahead of and behind the field, emitting thick clouds of dust that hung in the humid air and settled in runners’ lungs as they ran. The afternoon temperatures hovered around 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32° Celsius), ensuring that athletes were not merely racing one another but also their physical capabilities.

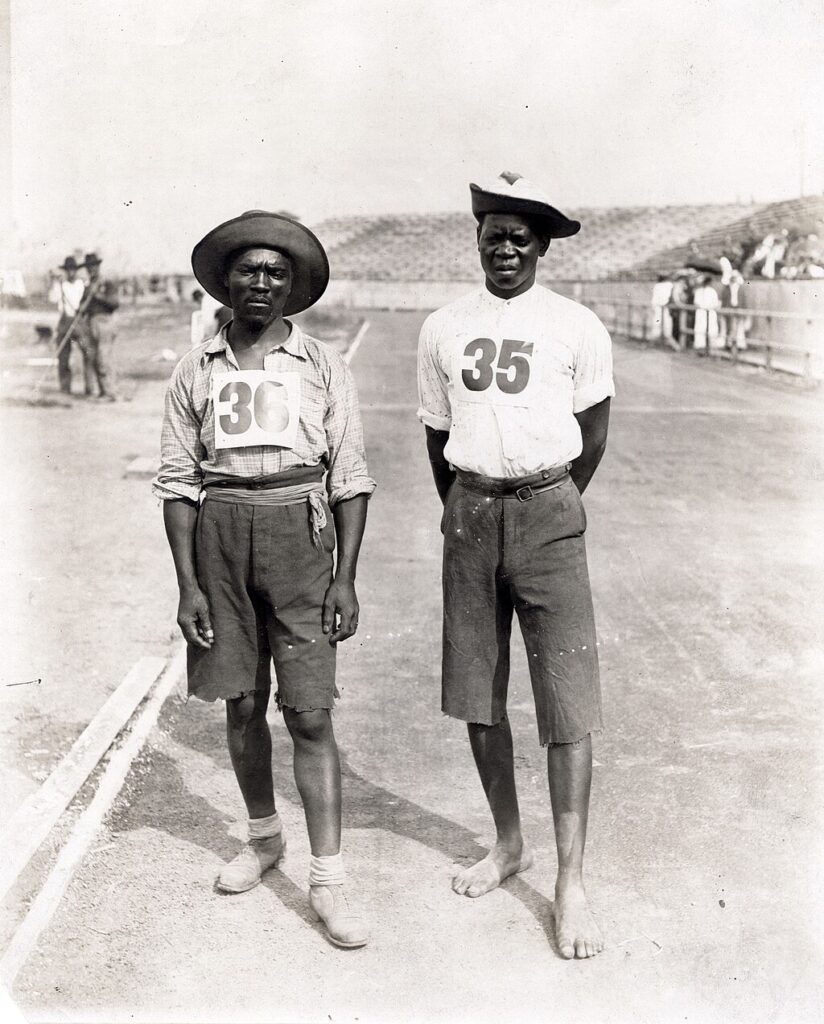

The first Black marathoners in Olympic history

Incidentally, the 1904 World Fair was also taking place in St Louis, and among the many contingents was a South African exhibit (South Africa had not become a dominion yet, and was still a colony under the British Empire), including two Tswana men, Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiani, being displayed as ‘savages’. Both were experienced long-distance runners who had served as messengers during the Second Boer War, and they chose to enter the marathon, becoming the first black participants from Africa to take part in the Olympics. The apartheid regime that would later grip their country prevented any other Black South Africans from competing in the Olympics until the 1990s.

An event characterised by poor organisation, erratic officiating and an unusual penchant for chaos, the marathon began with 32 athletes from seven nations, including the United States, France, Cuba, Greece, the Orange River Colony, Great Britain and Canada. Only 14 could finish the race.

Giving runners rat poison and brandy instead of water (for the love of science)

The first notable instance of performance-enhancing drugs in sport may not have arrived in the form one might expect. The eventual winner, Thomas Hicks, had chanced upon trainers devoted to a fashionable early 20th-century theory: that purposeful dehydration, rather than hydration, was the key to endurance.

Seventeen miles into the race, Thomas Hicks was struggling badly. The afternoon heat had not been kind, and he was visibly dehydrated. Rather than offering the radical solution of water, his handlers provided him with a stimulant made of strychnine (rat poison), egg whites and brandy.

Remarkably, it worked (albeit briefly) [Don’t try this at home, people]. Hicks continued until roughly the twenty-mile mark, where he collapsed again, beyond the reach of further liquid courage. His trainers then assisted him, or more accurately, carried him, onward to the finish line, an intervention that was not yet considered disqualifying. By the end, Hicks was incoherent and hallucinating, and doctors later suggested he might have died without immediate treatment.

After the actual first-place finisher, Fred Lorz, was disqualified, Hicks was declared the marathon’s winner. Upon winning, with the slowest time in Olympic history (3:28:53), he reportedly said, “The terrific hills simply tear a man to pieces.”

Some good ol’ fashioned cheating

Spectators, who had been waiting far too long for any sign of the runners, were finally rewarded with a dramatic arrival of the American, Fred Lorz, huffing his way into the stadium. The crowd went ecstatic. Lorz had his photo taken with Roosevelt’s daughter, who then even placed a wreath upon his head. For a brief moment, St. Louis believed it had witnessed an Olympic triumph.

It had, in fact, witnessed an Olympic detour.

Right before he could accept the gold medal, one witness announced that Lorz had apparently abandoned the race roughly nine miles (14km) in, exhausted and dehydrated. His trainer, moved by sympathy or perhaps practicality, offered him a ride back toward the stadium. The automobile carried them approximately eleven miles (17km) further along the course before breaking down. At this point, Lorz, now rested and conveniently far ahead of the field, stepped out of the car and simply resumed running.

Upon being confronted by furious race officials, Lorz admitted his deception with little resistance. The episode was explained, somewhat implausibly, as a joke. A sorry interpretation that did not survive the rules of the Olympic Games, even in 1904.

A Cuban runner, an Orchard, and other complications

Andarín Carbajal, a Cuban mailman, had relied on funds raised by his community to finance the journey to St. Louis. The plan was straightforward, at least until Carbajal reached New Orleans and promptly lost the entire sum in an ill-advised gambling episode. Suddenly, without money and rapidly running out of time, he resorted to hitchhiking north in a frantic attempt to reach the marathon before it began.

Carbajal arrived in St. Louis just in time for the starting gun, having reportedly gone nearly forty hours without food. He was dressed in his regular mailman attire of formal slacks, a long-sleeved shirt, and a beret. A sympathetic bystander, recognising the practical limitations of running a marathon in trousers, produced a pair of scissors and transformed them into improvised shorts moments before the race began. Carbajal accepted the adjustment. The beret, however, remained poised on his head.

Carbajal’s priorities were understandably inclined towards food, given his condition. At one point, he noticed a spectator eating two peaches and asked if he might have them. When the spectator declined, Carbajal stole both the peaches and continued down the course.

Without trainers, supplements, or any organised support, he later wandered into an orchard and helped himself to a few apples. Unfortunately, the apples were rotten. Severe stomach cramps followed, and Carbajal, faced with the physiological consequences of his actions, did what any exhausted endurance athlete might consider. He lay down in the shade and took a nap.

Remarkably, despite pausing mid-marathon for sleep, Carbajal still finished fourth overall, an outcome that speaks as much to his resilience as to the race’s condition.

The runner who nearly died

American runner William Garcia would likely remember the dust of the road more than the distance. The roads had become so thick with dirt and exhaust that runners were forced to inhale clouds of abrasive particles for hours. Garcia became violently ill and collapsed along the course, later suffering internal bleeding that doctors attributed to the extreme conditions.

In fact, the dust had coated his oesophagus and ripped his stomach lining. He was found lying prone on the roadside and taken for urgent medical treatment. He survived, but only narrowly.

One might assume that a near-fatal collapse in the middle of an Olympic marathon would prompt officials to reconsider the event’s design, if not cancel it outright. But that was not to be. The race continued.

A joust with dogs

Photographs from the day show that Len Taunyane competed barefoot, a detail that, remarkably, was not his greatest disadvantage. Taunyane’s difficulties were of a more canine variety, with wild dogs reportedly chasing him nearly a mile off course. Despite such interruptions, both Taunyane and Jan Mashiani were among the relatively few who managed to finish.

Taunyane, in particular, had been expected to place much higher. Instead, he finished ninth. No adjustment was made for his chance encounter, and he simply had to accept the results.

The aftermath

The 1904 marathon was so spectacularly mismanaged that it very nearly doomed the event’s future altogether. In the aftermath, serious questions were raised about whether the marathon belonged in the Olympic programme at all, given that St. Louis had completely transformed what should have been a test of endurance into an uncontrolled medical trial conducted on dusty public roads. That the race survived is, in hindsight, one of the more surprising outcomes of the day.

Fortunately for modern marathoners, the event retained its coveted Olympic place, though it took several more years for basic common sense to be prevalent. For a time, stimulants like brandy, champagne, and even strychnine were treated with more enthusiasm than water, and dehydration was regarded as an added advantage. The sport, however, like the athletes, eventually recovered.

Carbajal went on to build an unlikely legend from his chaotic fourth-place finish. Others, however, were less fortunate; several runners collapsed, one nearly died, and the winner himself crossed the line in a state bordering on unconsciousness. Yet the marathon endured, perhaps because the Olympics have always had a certain tolerance for the spectacle.

The organisers of every Olympic marathon since then take comfort in one reassuring fact. No matter how difficult the logistics, no matter how many mishaps occur, it is extraordinarily unlikely that they will ever manage to stage anything quite as catastrophically absurd as St. Louis in 1904.